First-of-their-kind snapshots reveal byproduct crippling powerful, experimental cells

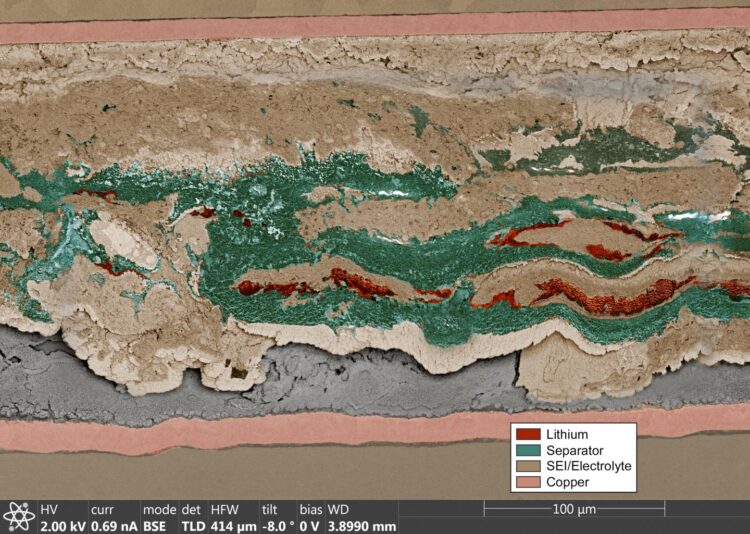

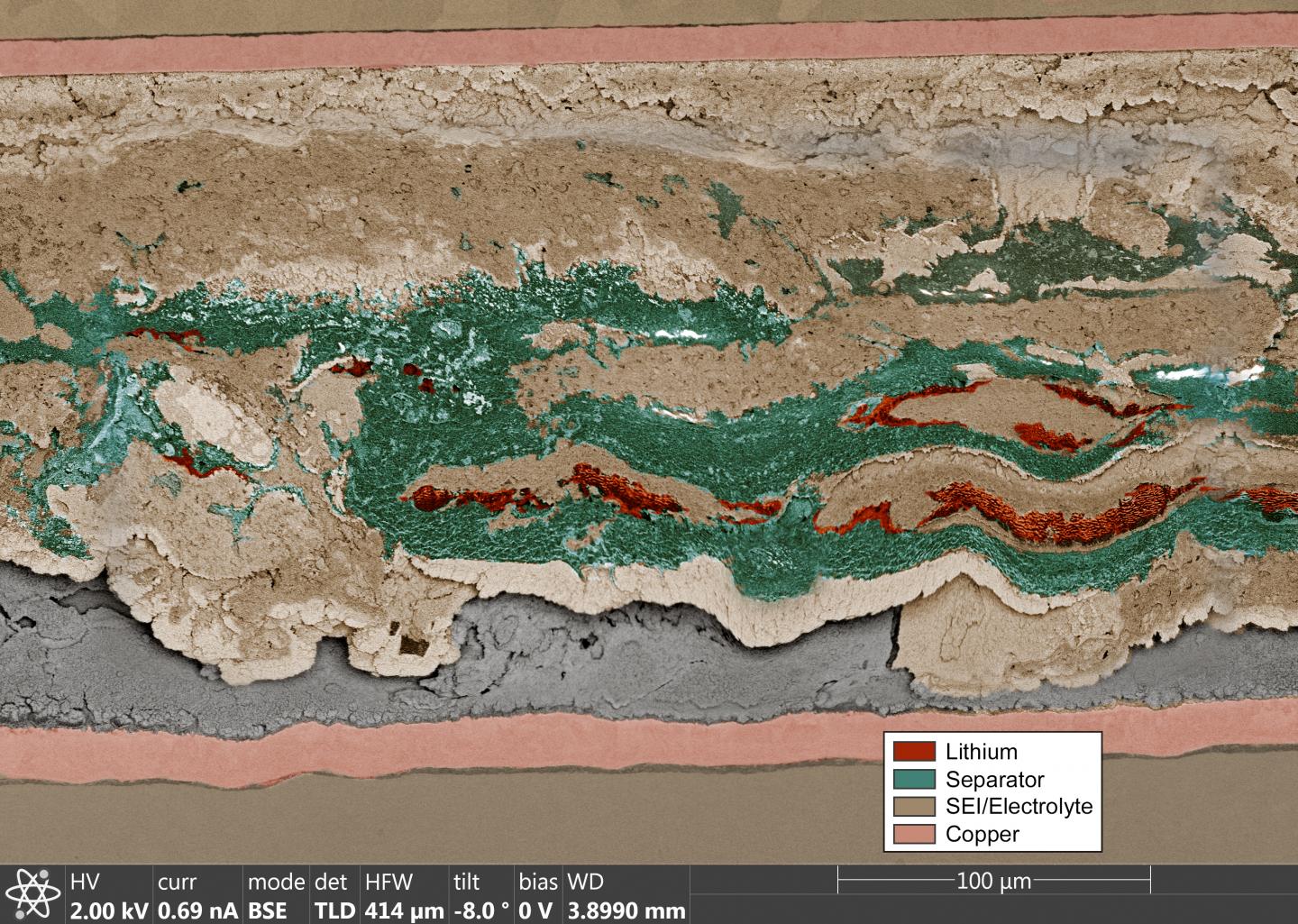

Credit: Katie Jungjohann, Sandia National Laboratories

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — For decades, scientists have tried to make reliable lithium-metal batteries. These high-performance storage cells hold 50% more energy than their prolific, lithium-ion cousins, but higher failure rates and safety problems like fires and explosions have crippled commercialization efforts. Researchers have hypothesized why the devices fail, but direct evidence has been sparse.

Now, the first nanoscale images ever taken inside intact, lithium-metal coin batteries (also called button cells or watch batteries) challenge prevailing theories and could help make future high-performance batteries, such as for electric vehicles, safer, more powerful and longer lasting.

“We’re learning that we should be using separator materials tuned for lithium metal,” said battery scientist Katie Harrison, who leads Sandia National Laboratories’ team for improving the performance of lithium-metal batteries.

Sandia scientists, in collaboration with Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., the University of Oregon and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, published the images recently in ACS Energy Letters. The research was funded by Sandia’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development program and the Department of Energy.

Internal byproduct builds up, kills batteries

The team repeatedly charged and discharged lithium coin cells with the same high-intensity electric current that electric vehicles need to charge. Some cells went through a few cycles, while others went through more than a hundred cycles. Then, the cells were shipped to Thermo Fisher Scientific in Hillsboro, Oregon, for analysis.

When the team reviewed images of the batteries’ insides, they expected to find needle-shaped deposits of lithium spanning the battery. Most battery researchers think that a lithium spike forms after repetitive cycling and that it punches through a plastic separator between the anode and the cathode, forming a bridge that causes a short. But lithium is a soft metal, so scientists have not understood how it could get through the separator.

Harrison’s team found a surprising second culprit: a hard buildup formed as a byproduct of the battery’s internal chemical reactions. Every time the battery recharged, the byproduct, called solid electrolyte interphase, grew. Capping the lithium, it tore holes in the separator, creating openings for metal deposits to spread and form a short. Together, the lithium deposits and the byproduct were much more destructive than previously believed, acting less like a needle and more like a snowplow.

“The separator is completely shredded,” Harrison said, adding that this mechanism has only been observed under fast charging rates needed for electric vehicle technologies, but not slower charging rates.

As Sandia scientists think about how to modify separator materials, Harrison says that further research also will be needed to reduce the formation of byproducts.

Scientists pair lasers with cryogenics to take ‘cool’ images

Determining cause-of-death for a coin battery is surprisingly difficult. The trouble comes from its stainless-steel casing. The metal shell limits what diagnostics, like X-rays, can see from the outside, while removing parts of the cell for analysis rips apart the battery’s layers and distorts whatever evidence might be inside.

“We have different tools that can study different components of a battery, but really we haven’t had a tool that can resolve everything in one image,” said Katie Jungjohann, a Sandia nanoscale imaging scientist at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies. The center is a user facility jointly operated by Sandia and Los Alamos national laboratories.

She and her collaborators used a microscope that has a laser to mill through a battery’s outer casing. They paired it with a sample holder that keeps the cell’s liquid electrolyte frozen at temperatures between minus 148 and minus 184 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 100 and minus 120 degrees Celsius, respectively). The laser creates an opening just large enough for a narrow electron beam to enter and bounce back onto a detector, delivering a high-resolution image of the battery’s internal cross section with enough detail to distinguish the different materials.

The original demonstration instrument, which was the only such tool in the United States at the time, was built and still resides at a Thermo Fisher Scientific laboratory in Oregon. An updated duplicate now resides at Sandia. The tool will be used broadly across Sandia to help solve many materials and failure-analysis problems.

“This is what battery researchers have always wanted to see,” Jungjohann said.

###

Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration. Sandia Labs has major research and development responsibilities in nuclear deterrence, global security, defense, energy technologies and economic competitiveness, with main facilities in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Livermore, California.

Media Contact

Troy Rummler

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.