The combination of smart city lighting and satellite imagery allows measurements of the contribution of street lights to urban lighting for the first time, and gives new hints for how to fight light pollution

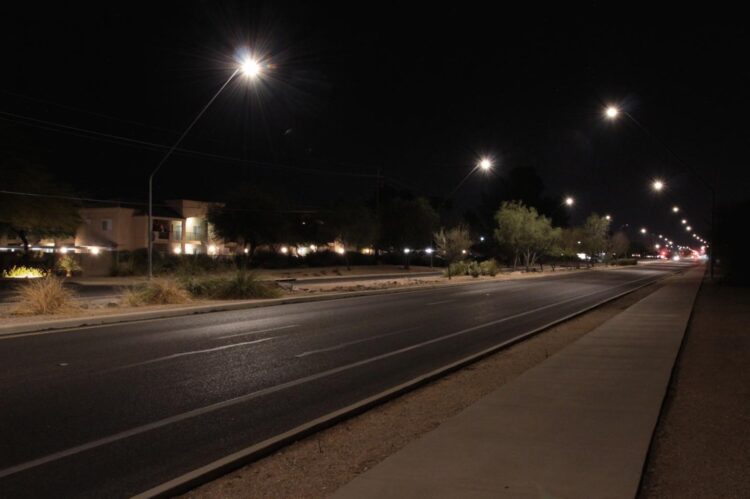

Credit: John Barentine

When satellites take pictures of Earth at night, how much of the light that they see comes from streetlights? A team of scientists from Germany, the USA, and Ireland have answered this question for the first time using the example of the U.S. city of Tucson, thanks to “smart city” lighting technology that allows cities to dim their lights. The result: only around 20 percent of the light in the satellite images of Tucson comes from streetlights. The study is published today in the journal Lighting Research & Technology.

The team conducted an experiment by changing the brightness of streetlights in the city of Tucson, Arizona, USA, and observing how this changed how bright the city appeared from space. Dr. Christopher Kyba from the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences led the team that conducted the experiment, and said the work is important because it shows that smart city technologies can be used to perform city-scale experiments. “When sensors and control systems are installed throughout an entire city, it is possible to make a change in how the city works, and then measure the impact that change has on the environment, even from outer space,” Kyba said.

Over a period of 10 days in March and April of 2019, Tucson officials changed the brightness settings for about 14,000 of the city’s 19,500 streetlights. Usually, most streetlights in Tucson start out at 90 per cent of their maximum possible illumination, and dim to 60 per cent at midnight. During the experiment, the city instead dimmed lights all the way down to 30 per cent on some nights, and brightened them up to 100 per cent on others. The city lights were observed by the US-operated Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite, which is famous for its global maps of light at night. The satellite took cloud-free images of Tucson on four nights during the test, and on two other nights with regular lighting after the test. By comparing the city brightness on the 6 different nights, the researchers found that on a normal night, only about 20 per cent of the light in satellite images of Tucson comes from streetlights.

The results have important implications for sustainability, according to study co-author Dr. John Barentine from the International Dark-Sky Association. In a second experiment conducted at the same time, Barentine, Kyba and their co-authors measured the sky brightness over Tucson from the ground. They examined how varying the illuminance of street lamps affected the sky brightness, and showed that as with light emissions seen from space, most of the sky brightness over Tucson is also due to other sources. “Taken together, these studies show that in a city with well-designed streetlights, most of the light emissions and light pollution come from other lights,” Barentine explaines, including light sources such as bright shop windows, lit signs and facades, or sport fields. The authors say that local and national governments therefore need to think about more than just street lighting when trying to reduce light pollution.

According to the researchers, the difference in the streetlighting brightness on the different nights is barely perceptible to the people on the street, as our eyes quickly adapt to the light levels. They report that the city received no comments or complaints about the changed lighting during the test. There is also no evidence or suggestion that reducing lighting levels as part of the experiment had any adverse effect on public safety.

Kyba is therefore excited by the idea of performing such experiments more regularly, and in other municipalities. “Instead of dimming lights to the same level late each night, a city could instead dim to 45% on even days and 55% on odd days,” Kyba suggested. “City residents wouldn’t notice any difference, but that way we could measure how the contribution of different light types is changing over time.”

###

About GFZ

The GFZ is Germany’s national research center for the solid Earth Sciences. Its mission is to deepen the knowledge of the dynamics of the solid Earth, and to develop solutions for grand challenges facing society. These challenges include anticipating the hazards arising from the Earth’s dynamic systems and mitigating the associated risks to society; securing our habitat under the pressure of global change; and supplying energy and mineral resources for a rapidly growing population in a sustainable manner and without harming the environment.

Original study:

C.C.M. Kyba, A. Ruby, H.U. Kuechly, B. Kinzey, N. Miller, J. Sanders, J. Barentine, R. Kleinodt, B. Espey. Direct measurement of the contribution of street lighting to satellite observations of nighttime light emissions from urban areas. Lighting Research & Technology (LR&T), October 2020. DOI: 10.1177/1477153520958463

Additional study:

John C. Barentine, František Kundracik, Miroslav Kocifaj, Jeessie C. Sanders, Gilbert A. Equerdo, Adam M. Dalton, Bettymaya Foott, Ablert Grauer, Scott Tucker, Christopher C.M. Kyba. Recovering the city street lighting fraction from skyglow measurements in a large-scale municipal dimming experiment. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, Volume 253, September 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2020.107120

Scientific contacts

Dr. Christopher Kyba

Remonte Sensing and Geoinformatics

Helmholtz Centre Potsdam

GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +49 331 288 28973

Dr. John Barentine

International Dark-Sky Association

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +1 520 347 6363

Media contact

Josef Zens

Head of Public and Media Relations

Helmholtz Centre Potsdam

GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences

Telegrafenberg

14473 Potsdam

Phone: +49 331 288-1040

Email: [email protected]

Media Contact

Dr. Christopher Kyba

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.