Paleontologists working in museum collections in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany have identified five additional specimens of a 240-million-year-old ichthyosaur, named Besanosaurus leptorhynchus, which was previously known from a single fossil housed

Credit: Gabriele Bindellini and Marco Auditore, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Middle Triassic ichthyosaurs are rare, and mostly small in size. The new Besanosaurus specimens described in the peer-reviewed journal PeerJ – the Journal of Life and Environmental Sciences – by Italian, Swiss, Dutch and Polish paleontologists provide new information on the anatomy of this fish-like ancient reptile, revealing its diet and exceptionally large adult size: up to 8 meters, a real record among all marine predators of this geological epoch. In fact, Besanosaurus is the earliest large-sized marine diapsid – the group to which lizards, snakes, crocodiles, and their extinct cousins belong to – with a long and narrow snout.

Besanosaurus leptorhynchus was originally discovered near Besano (Italy) three decades ago, during systematic excavations led by the Natural History Museum of Milan. The PeerJ article re-examines its skull bones in detail and assigns five additional fossils to this species: two previously undescribed fossil specimens, and two fossils previously referred to a different species (Mikadocephalus gracilirostris), which turns out to be not valid due to lack of significant anatomical differences with Besanosaurus.

The six specimens vary mainly in size and likely represent different growth stages. According to this re-analysis, Besanosaurus is the oldest and basal-most representative of a group of ichthyosaurs known as shastasaurids.

All specimens, housed in museums in Milan, Zurich, and Tübingen were collected in the last century from the bituminous black shales of the Monte San Giorgio area (Italy/Switzerland, UNESCO World Heritage), which were deposited some 240 million years ago at the oxygen-depleted bottom of a peculiar marine basin. The locality is famous worldwide for its rich fossil fauna that, besides ichthyosaurs, includes many other marine and semiaquatic reptiles, a variety of fish, and hard-shelled invertebrates.

“The extremely long and slender rostrum suggests that Besanosaurus primarily fed on small and elusive prey, feeding lower in the food web than an apex predator: a novel ecological specialisation never reported before this epoch of the Triassic in a large diapsid reptile. This might have triggered an increase of body size and lowered competition among the diverse ichthyosaurs that co-existed in this part of the Tethys Ocean”, says Gabriele Bindellini of the Earth Science Dept. of Milan University, first author of this study.

“Studying these fossils was a real challenge. All Besanosaurus specimens have been extremely compressed by deep time and rock pressure, so we used advanced medical CT scanning, photogrammetry techniques and comparisons with other ichthyosaurs to reveal their hidden anatomy and reconstruct their skulls in 3D, bone by bone”, remarks Cristiano Dal Sasso of the Natural History Museum of Milan, senior author of the PeerJ article, who in 1996 originally described and named Besanosaurus.

Interestingly, the Italian researchers started re-studying the Milan Besanosaurus roughly at the same time an international team including Andrzej Wolniewicz (IP PAS, Warsaw), Feiko Miedema (SMNS, Stuttgart), and Torsten Scheyer (UZH, Zurich) started working on the Swiss specimens. “Rather than doing parallel studies, we pooled our data and efforts and pulled on the same string, to enhance our understanding of these fascinating extinct animals”, adds Torsten Scheyer.

###

Images:

Image 1: The first and most complete fossil of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus is a pregnant female (containing one embryo) on display at the Milan Natural History Museum, together with a fiberglass reconstruction of its in-life aspect. 16.500 hours of manual preparation were needed to expose the entire skeleton, embedded in a 330×270 cm black shale layer. Credit: Gabriele

Bindellini, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

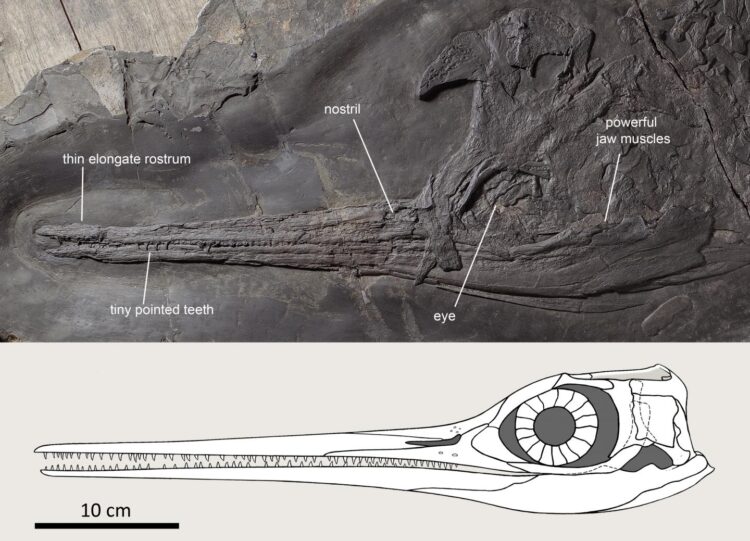

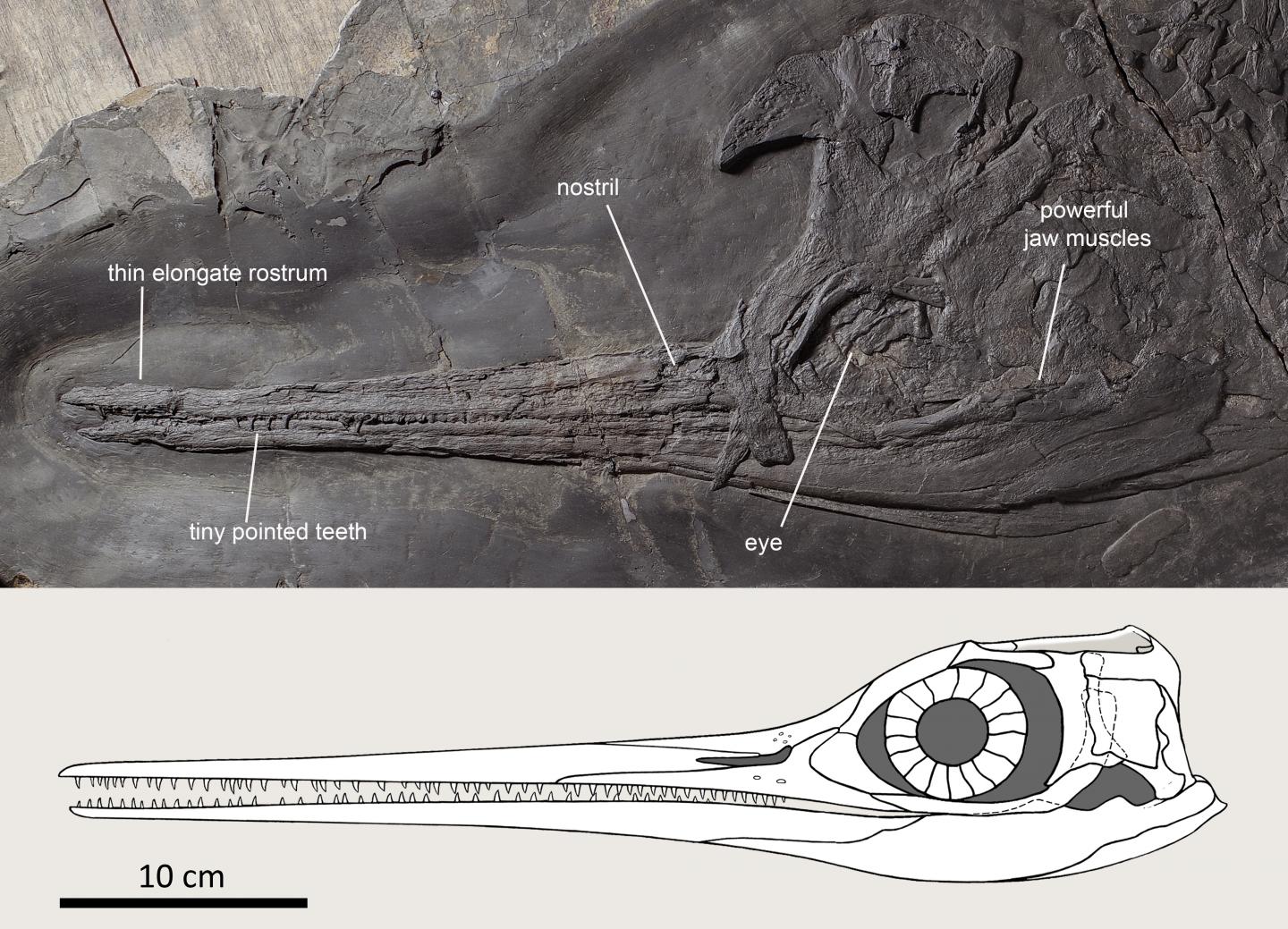

Image 2: The skull of the type specimen of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus is characterized by extreme longirostry (i.e., thin elongate snout), and equipped with tiny pointed teeth, perfect for catching small fish and extinct cousins of squids with rapid snapping moves of the head and jaws. Credits: Gabriele Bindellini and Marco Auditore, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 3: A view of Lake Lugano from Monte San Giorgio, between Lombardy (Italy, left) and Canton Ticino (Switzerland, right). Ichthyosaurs are among the most abundant fossils of this UNESCO World Heritage locality, which protects a unique paleo-biodiversity dating back to the Middle Triassic (240 million of years ago). Credit: Gabriele Bindellini.

Image 4: At the Zurich Institute and Museum of Paleontology, Gabriele Bindellini measures the orbital diameter of a subadult Besanosaurus leptorhynchus. This fossil preserves some three-dimensional anatomy, which helped to re-define the “identity card” of the species. Credit: Cristiano Dal Sasso.

Image 5: At the Zurich Institute and Museum of Paleontology, Cristiano Dal Sasso opens the display case of a remarkably large ichthyosaur specimen that, if complete, would have measured 8 meters in length. Although disarticulated, the skull indicates it is another Besanosaurus… Credit: Gabriele Bindellini.

Image 6: Reconstruction of Besanosaurus. In spite of their fish-like aspect, ichthyosaurs were reptiles. They were perfectly adapted to marine life through large modifications of their land-dwelling ancestors’ limbs into paddles. Dorsal fins and crescentic tails also developed in later, more advanced forms. Pencil by Fabio Fogliazza digitally modified by Gabriele Bindellini, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 7. The “Sasso Caldo” site, near Besano (Varese, Italy) in 1995. This outcrop is characterized by a regular alternance of thin black bituminous shales, and thicker grey-whitish dolomitized layers. Fossils are found in both, although in the shales the specimens are highly deformed. Photo by Giorgio Teruzzi, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 8. Spring 1993, Besano (Varese, Italy): a snapshot of the recovery of the most complete specimen of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus. To avoid damaging the fossil, the bones of the large ichthyosaur were detected in cross-section, along the cuts of the slabs, without splitting the layer that embedded them firmly. The chisels in the photo were used only to detach the fossil-bearing layer from the underlying one. Photo by Cristiano Dal Sasso, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 9. At the Fondazione Ospedale Maggiore di Milano, on the CT screen appears the Besanosaurus skull, with the orbital cavity (bottom center) surrounded by the bones of the temporal region. Photo by Cristiano Dal Sasso.

Image 10. At the Natural History Museum of Milan, the preparators of the Laboratory of Paleontology remove the silicon layer that, poured on the recomposed skeleton of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus, allows to produce identical replicas of the original fossil. © Photo by Guido Alberto Rossi and Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 11. In the thoracic region of the Milan Besanosaurus, where the stomach was located, food remains are preserved, including this tiny hooklet from a squid relative’s arm. Cephalopods were preferred prey for several species of ichthyosaurs. Photo by Gabriele Bindellini, © Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano.

Image 12. The “Sasso Caldo” site of Besano (Varese, Italy) as it appears today. The outcrop is extremely rich in fossils in almost every rock layer. In this picture, paleontologist Cristiano Dal Sasso indicates with his right hand the bituminous layer n. 65, in which the former Besanosaurus was embedded, and with his left hand the layer n. 63, which provided two small ichthyosaurs of the genus Mixosaurus. Photo by Gabriele Bindellini.

Image 13. At the Fondazione Ospedale Maggiore di Milano, paleontologist Gabriele Bindellini (left) and a student of the Degree in Medical Techniques of Radiology, Alessandro Crasti (right), scan the skull of Besanosaurus leptorhynchus before shifting it into the CT ring. Photo by Cristiano Dal Sasso.

Image 14. At the Institute and Museum of Paleontology of the Zurich University, paleontologists Cristiano Dal Sasso (left) and Torsten Scheyer (right) chat in front of the largest Besanosaurus – recently identified as such – unearthed in the first half of the last century from Swiss mines of Monte San Giorgio. If complete, this specimen would have approached 8 meters in length. Photo by Gabriele Bindellini.

CONTACTS

Dr. Cristiano Dal Sasso

Sezione di Paleontologia dei Vertebrati

Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano

Corso Venezia 55 – Milano 20121

Tel. 02 88463301

Email: [email protected]

Dr. Gabriele Bindellini

Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra “Ardito Desio”

Università degli Studi di Milano

Tel. 349 6220170

Email: [email protected]

Full Media Pack including images and videos and extended press releases in ENGLISH and ITALIAN:

https:/

About:

PeerJ is an Open Access publisher of seven peer-reviewed journals covering biology, environmental sciences, computer sciences, and chemistry. With an emphasis on high-quality and efficient peer review, PeerJ‘s mission is to give researchers the publishing tools and services they want with a unique and exciting experience. All works published by PeerJ are Open Access and published using a Creative Commons license (CC-BY 4.0). PeerJ is based in San Diego, CA and the UK and can be accessed at peerj.com

PeerJ – the Journal of Life and Environmental Sciences is the peer-reviewed journal for Biology, Medicine and Environmental Sciences. PeerJ has recently added 15 areas in environmental science subject areas, including Natural Resource Management, Climate Change Biology, and Environmental Impacts.

peerj.com/environmental-sciences

Across its journals, PeerJ has an Editorial Board of over 2,000 respected academics, including 5 Nobel Laureates. PeerJ was the recipient of the 2013 ALPSP Award for Publishing Innovation. PeerJ Media Resources (including logos) can be found at: peerj.com/about/press

Media Contacts

For PeerJ: email: [email protected] , https:/

Note: If you would like to join the PeerJ Press Release list, please register at: http://bit.

Media Contact

Dr. Cristiano Dal Sasso

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.