In a university swimming pool, scientists and their underwater cameras watch carefully as a coiled shell is released from a pair of metal tongs. The shell begins to move under its own power, giving the researchers a glimpse into what the oceans might have looked like millions of years ago when they were full of these ubiquitous animals.

Credit: David Peterman/University of Utah

In a university swimming pool, scientists and their underwater cameras watch carefully as a coiled shell is released from a pair of metal tongs. The shell begins to move under its own power, giving the researchers a glimpse into what the oceans might have looked like millions of years ago when they were full of these ubiquitous animals.

This isn’t Jurassic Park, but it is an effort to learn about ancient life by recreating it. In this case, the recreations are 3-D-printed robots designed to replicate the shape and motion of ammonites, marine animals that both preceded and were contemporaneous with the dinosaurs.

The robotic ammonites allowed the researchers to explore questions about how shell shapes affected swimming ability. They found trade-offs between stability in the water and maneuverability, suggesting that the evolution of ammonite shells explored different designs for different advantages rather than converged toward a single best design.

“These results reiterate that there is no single optimum shell shape,” says David Peterman, a postdoctoral fellow in the University of Utah’s Department of Geology and Geophysics.

The study is published in Scientific Reports and supported by the National Science Foundation.

Bringing ammonites to “life”

For years, Peterman and Kathleen Ritterbush, assistant professor of geology and geophysics, have been exploring the hydrodynamics, or physics of moving through the water, of ancient shelled cephalopods, including ammonites. Cephalopods today include octopuses and squid, with only one group sporting an external shell—the nautiluses.

Before the current era, cephalopods with shells were everywhere. Although their rigid coiled shells would have impacted their free movement through the water, they were phenomenally successful evolution-wise, persisting for hundreds of millions of years and surviving every mass extinction.

“These properties make them excellent tools to study evolutionary biomechanics,” Peterman says, “the story of how benthic (bottom-dwelling) mollusks became among the most complex and mobile group of marine invertebrates. My broader research goal is to provide a better understanding of these enigmatic animals, their ecosystem roles, and the evolutionary processes that have shaped them.”

Peterman and Ritterbush previously built life-sized 3-D weighted models of cone-shaped cephalopod shells and found, through releasing them in pools, that the ancient animals likely lived a vertical life, bobbing up and down through the water column to find food. These models’ movements were governed solely by buoyancy and the hydrodynamics of the shell.

But Peterman has always wanted to build models more similar to living animals.

“I have wanted to build robots ever since I developed the first techniques to replicate hydrostatic properties in physical models, and Kathleen strongly encouraged me as well,” Peterman says. “On-board propulsion enables us to explore new questions regarding the physical constraints on the life habits of these animals.”

Buoyancy became Peterman’s chief challenge. He needed the models to be neutrally buoyant, neither floating nor sinking. He also needed the models to be water-tight, both to protect the electronics inside and to prevent leaking water from changing the delicate buoyancy balance.

But the extra work is worth it. “New questions can be investigated using these techniques,” Peterman says, “including complex jetting dynamics, coasting efficiency, and the 3-D maneuverability of particular shell shapes.”

Three kinds of shells

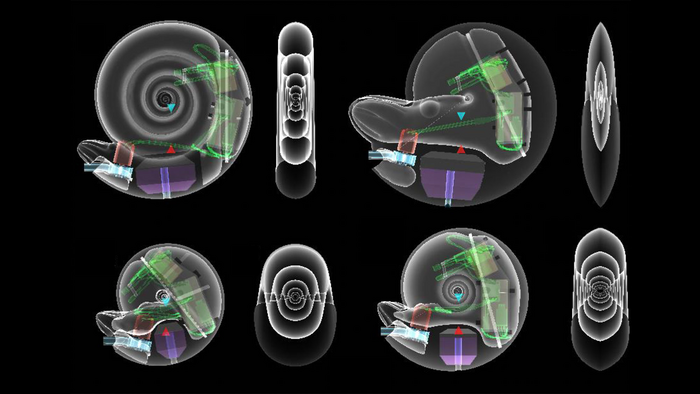

The researchers tested robotic ammonites with three shell shapes. They’re partially based on the shell of a modern Nautilus and modified to represent the range of ancient ammonites’ shell shapes. The model called a serpenticone had tight whorls and a narrow shell, while the sphaerocone model had few thick whorls and a wide, almost spherical shell. The third model, the oxycone, was somewhere in the middle: thick whorls and a narrow, streamlined shell. You can think of them occupying a triangular diagram, representing “end-members” of different shell characteristics.

“Every planispiral cephalopod to ever exist plots somewhere on this diagram,” Peterman says, allowing the properties for in-between shapes to be estimated.

Once the 3-D-printed models were built, rigged and weighted, it was time to go to the pool. Working first in the pool of Geology and Geophysics professor Brenda Bowen and later in the U’s Crimson Lagoon, Peterman and Ritterbush set up cameras and lights underwater and released the robotic ammonites, tracking their position in 3-D space throughout around a dozen “runs” for each shell type.

No perfect shell shape

By analyzing the data from the pool experiments, the researchers were looking for the pros and cons associated with each shell characteristic.

“We expected there to be various advantages and consequences for any particular shapes,” Peterman says. “Evolution dealt them a very unique mode of locomotion after liberating them from the seafloor with a chambered, gas-filled conch. These animals are essentially rigid-bodied submarines propelled by jets of water.” That shell isn’t great for speed or maneuverability, he says, but coiled-shell cephalopods still managed remarkable diversity through each mass extinction.

“Throughout their evolution, externally shelled cephalopods navigated their physical limitations by endlessly experimenting with variations on the shape of their coiled shells,” Peterman says.

So, which shell shape was the best?

“The idea that one shape is better than another is meaningless without asking the question—‘better at what?’” Peterman says. Narrower shells enjoyed less drag and more stability while traveling in one direction, improving their jetting efficiency. But wider, more spherical shells could more easily change directions, spinning on an axis. This maneuverability may have helped them catch prey or avoid slow predators (like other shelled cephalopods).

Peterman notes that some interpretations consider many ammonite shells as hydrodynamically “inferior” to others, limiting their motion too much.

“Our experiments, along with the work of colleagues in our lab, demonstrate that shell designs traditionally interpreted as hydrodynamically ‘inferior’ may have had some disadvantages but are not immobile drifters,” Peterman says. “For externally shelled cephalopods, speed is certainly not the only metric of performance.” Nearly every variation in shell design iteratively appears at some point in the fossil record, he says, showing that different shapes conferred different advantages.

“Natural selection is a dynamic process, changing through time and involving numerous functional tradeoffs and other constraints,” he says, “Externally-shelled cephalopods are perfect targets to study these complex dynamics because of their enormous temporal range, ecological significance, abundance, and high evolutionary rates.”

Find the full study here.

Journal

Scientific Reports

DOI

10.1038/s41598-022-13006-6

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Resurrecting extinct cephalopods with biomimetic robots to explore hydrodynamic stability, maneuverability, and physical constraints on life habits.

Article Publication Date

4-Jul-2022