Doctors are one step closer to having a risk biomarker to alert them to which of their pediatric stem cell transplant patients are likely to experience a potentially deadly side effect called sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS).

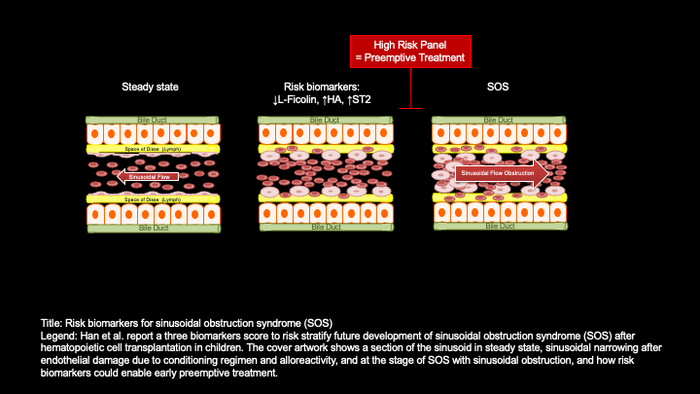

Credit: Illustration by Sophie Paczesny

Doctors are one step closer to having a risk biomarker to alert them to which of their pediatric stem cell transplant patients are likely to experience a potentially deadly side effect called sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS).

A team led by MUSC Hollings Cancer Center researcher Sophie Paczesny, M.D., Ph.D., published the results of its biomarker study in JCI Insight this month.

There is a drug, defibrotide, approved to treat SOS. Paczesny hopes the results of the biomarker study will encourage defibrotide’s manufacturer to conduct a multicenter clinical trial testing whether giving it to patients who test positive for the risk biomarkers before they begin to show symptoms can prevent SOS from developing.

“That’s my dream. These patients really need it,” she said. “Most of my colleagues on this study are physicians, so they really want me to move this forward because they still see a lot of patients being affected by this.”

Stem cell transplants can cure blood cancers and other blood disorders, but, as with other cancer treatments, they come with side effects.

SOS, sometimes called hepatic veno-occlusive disease, means that the veins in the liver are blocked. It’s not the most common side effect after an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant, or a stem cell transplant using donor cells: that would probably be graft-versus-host disease, which is the main focus of Paczesny’s research. But SOS occurs in a significant number of patients – 12.5% in this study – and can lead to multiorgan failure and death.

In addition, it can be harder to diagnose in children than in adults, and there are no clear risk factors that indicate who is likely to develop this condition, Paczesny said. Previous studies have looked at proactively giving defibrotide to all patients, but those studies showed no clear benefit, she said. The drug is also rather expensive, so limiting it to those who would truly benefit makes sense.

In a previous study, Paczesny’s team gathered samples from children who developed SOS and identified potential biomarkers based on either unusually high or unusually low levels. Those potential biomarkers included ST2, a receptor that is also used as a biomarker of cardiac stress; hyaluronic acid, best known as an anti-aging ingredient in skin care products but also a component of connective tissue that’s used as a biomarker of liver fibrosis; and L-ficolin, a protein expressed in the liver that plays a role in the innate immune system.

In this study, conducted at four academic medical centers across the country, the researchers wanted to see at what point the potential risk biomarkers would start showing unusual levels. They tested 80 patients’ plasma at two points in time: three days after the stem cell transplant and seven days after the stem cell transplant. SOS typically occurs within a month of transplant, so those two points in time would presumably give doctors enough time to act. And, in fact, the researchers found that measuring those biomarkers on day three following the transfer of hematopoietic cells did indicate which patients would go on to develop SOS.

“Using the combination of the three biomarkers as a score, recipients with a positive score were 9.3 times more likely to develop SOS,” they reported.

Patients with positive scores were also more likely to die within 100 days of the transplant.

The researchers noted that this study appeared to be the first prospective biomarker analysis for donor stem cell transplant.

Besides identifying patients at risk of SOS, the biomarkers could possibly also be used to monitor how well patients respond to treatment with defibrotide. If a study with a larger group shows that the biomarkers are effective trackers, then doctors could use them to decide when the patient no longer needs defibrotide, rather than giving everyone the same 21-day treatment.

About MUSC Hollings Cancer Center

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center is South Carolina’s only National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center with the largest academic-based cancer research program in the state. The cancer center comprises more than 130 faculty cancer scientists and 20 academic departments. It has an annual research funding portfolio of more than $44 million and sponsors more than 200 clinical trials across the state. Dedicated to preventing and reducing the cancer burden statewide, the Hollings Office of Community Outreach and Engagement works with community organizations to bring cancer education and prevention information to affected populations. Hollings offers state-of-the-art cancer screening, diagnostic capabilities, therapies and surgical techniques within its multidisciplinary clinics. Hollings specialists include surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, psychologists and other clinical providers equipped to provide the full range of cancer care. For more information, visit hollingscancercenter.musc.edu.

Journal

JCI Insight

DOI

10.1172/jci.insight.168221

Article Title

Prospective assessment of risk biomarkers of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation

Article Publication Date

18-Apr-2023

COI Statement

SP holds a patent on “Methods for detecting sinusoidal obstructive syndrome (SOS)” (US Patent 11,193,945 B2).