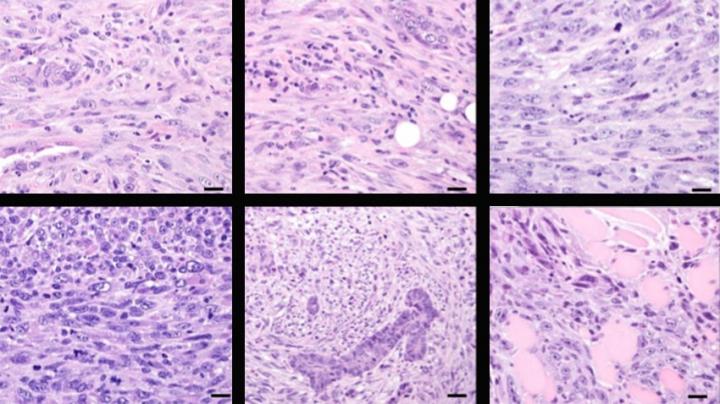

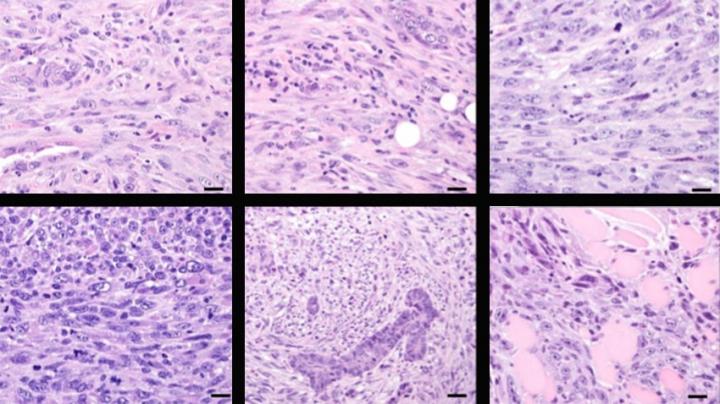

Credit: University of Michigan Health System

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — For more than a decade, Celina Kleer, M.D., has been studying how a poorly understood protein called CCN6 affects breast cancer. To learn more about its role in breast cancer development, Kleer's lab designed a special mouse model – which led to something unexpected.

They deleted CCN6 from the mammary gland in the mice. This type of model allows researchers to study effects specific to the loss of the protein. As Kleer and her team checked in at different ages, they found delayed development and mammary glands that did not develop properly.

"After a year, the mice started to form mammary gland tumors. These tumors looked identical to human metaplastic breast cancer, with the same characteristics. That was very exciting," says Kleer, Harold A. Oberman Collegiate Professor of Pathology and director of the Breast Pathology Program at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Metaplastic breast cancer is a very rare and aggressive subtype of triple-negative breast cancer – a type considered rare and aggressive of its own. Up to 20 percent of all breast cancers are triple-negative. Only 1 percent are metaplastic.

"Metaplastic breast cancers are challenging to diagnose and treat. In part, the difficulties stem from the lack of mouse models to study this disease," Kleer says.

So not only did Kleer gain a better understanding of CCN6, but her lab's findings open the door to a better understanding of this very challenging subtype of breast cancer. The study is published in Oncogene.

"Our hypothesis, based on years of experiments in our lab, was that knocking out this gene would induce breast cancer. But we didn't know if knocking out CCN6 would be enough to unleash tumors, and if so, when, or what kind," Kleer says. "Now we have a new mouse model, and a new way of studying metaplastic carcinomas, for which there's no other model."

One of the hallmarks of metaplastic breast cancer is that the cells are more mesenchymal, a cell state that enables them to move and invade. Likewise, researchers saw this in their mouse model: knocking down CCN6 induced the process known as the epithelial to mesenchymal transition.

"This process is hard to see in tumors under a microscope. It's exciting that we see this in the mouse model as well as in patient samples and cell lines," Kleer says.

The researchers looked at the tumors developed by mice in their new model and identified several potential genes to target with therapeutics. Some of the options, such as p38, already have antibodies or inhibitors against them.

The team's next steps will be to test these potential therapeutics in the lab, in combination with existing chemotherapies. They will also use the mouse model to gain a better understanding of metaplastic breast cancer and discover new genes that play a role it its development.

"Understanding the disease may lead us to better ways to attack it," Kleer says. "For patients with metaplastic breast cancer, it doesn't matter that it's rare. They want – and they deserve – better treatments."

###

Note to patients: To learn more about existing treatment options for metaplastic breast cancer, call the U-M Cancer AnswerLine at 800-865-1125.

Additional authors: Emily E. Martin, Wei Huang, Talha Anwar, Caroline Arellano-Garcia, Boris Burman, Jun-Lin Guan, Maria E. Gonzalez

Funding: National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA125577, R01 CA107469, F30 CA196084, R25 GM086262, P30 CA46592

Disclosure: None

Reference: Oncogene, doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.381

Resources:

U-M Cancer AnswerLine, 800-865-1125

U-M Comprehensive Cancer Center, http://www.mcancer.org

Michigan Health Lab, http://www.MichiganHealthLab.org

Media Contact

Nicole Fawcett

[email protected]

734-764-2220

@UMHealthSystem

http://www.med.umich.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag