The novel model mimics human acne and introduces new possibilities for targeted treatments and vaccines

Credit: UC San Diego Health

Researchers have long believed that Propionibacterium acnes causes acne. But these bacteria are plentiful on everyone’s skin and yet not everyone gets acne, or experiences it to the same degree. Genetic sequencing recently revealed that not all P. acnes are the same — there are different strains, some of which are abundant in acne lesions and some that are never found there.

Still, acne research and therapeutic development have been hampered by the lack of an animal model that replicates the human condition. When administered to mice, for example, P. acnes don’t cause long-term skin lesions and the mouse immune system rapidly clears away the bacteria. Now, however, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Cedars-Sinai and UCLA have developed a new mouse model that closely resembles human acne by adding one new factor — a synthetic sebum, the waxy skin secretion that increases in human adolescence.

For the first time, the model, described in a paper publishing March 7, 2019 in JCI Insight, allowed the researchers to directly compare “good” (health-associated) and “bad” (acne-associated) strains of P. acnes bacteria in a way that is more relevant to human acne than in previous attempts.

“Since we know exactly which genes differ between these strains, next we can pinpoint exactly what it is about the acne-associated strains that allows them to cause skin lesions,” said George Y. Liu, MD, PhD, professor and chief of the Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “And that information will help us develop new therapies that specifically block those acne-promoting factors, or tip the balance of a person’s skin chemistry in favor of the healthy strains.”

Liu was a faculty member at Cedars-Sinai at the time of the study.

Liu and team prepared synthetic sebum by following a recipe they found in a previous scientific study, a simple concoction of four ingredients — fatty acid, triglyceride, wax and squalene, a precursor compound to sterols, such as cholesterol and steroid hormones — in ratios that resemble human sebum. (Mice produce skin sebum, too, but its makeup is different.)

“When we started working with these bacteria and checked out the animal models others have been using over the years, we thought ‘we’ve got to come up with something better than this,'” Liu said. “Acne typically occurs when a person hits their teenage years …What’s the difference between a child’s skin and a teenager’s skin? Increased sebum production. And we were surprised to find how such a simple addition made a big difference in our ability to study acne.”

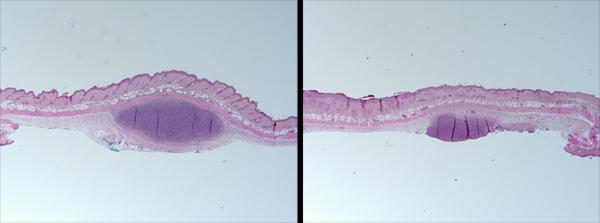

The researchers inoculated mice with P. acnes and applied fresh sebum daily. Without the sebum, the mice had minimal lesions and the bacteria were rapidly cleared from the site of administration. With the sebum alone, there was no effect on the skin.

But when Liu and team applied both sebum and acne-associated strains of P. acnes, they saw what looked like human acne, and the bacteria survived for weeks. These P. acnes strains also caused inflammation in the skin, as measured by elevated levels of inflammatory molecules called cytokines.

Then the researchers tried the same with health-associated strains of P. acnes — strains that aren’t found in human acne lesions. The same amount of bacteria was still present on the skin three days after inoculation, no matter the strain applied. But researchers could clearly see the differences between strains just by looking at the mice, Liu said. Lesions caused by acne-associated P. acnes strains scored approximately two times higher than lesions caused by health-associated strains in a measure that takes into account a lesion’s size, redness, dryness and degree of skin sloughing.

Unlike people, the mice in these experiments were all genetically identical. Liu said that’s important because it means that the differences in acne severity were due only to differences between the bacterial strains, not differences in the mice’s innate ability to react to the bacteria.

Next, the team hopes to improve upon its acne mouse model so they can achieve similar results when the bacteria are applied topically rather than administered by injection under the skin. They also want to study the genes that are unique to acne-associated P. acnes strains and determine what it is about human sebum that promotes these strains.

Liu said this information could help the team better understand who is at increased risk for acne, and how to develop personalized therapies and vaccines that target the acne-promoting bacterial factors or sebum components.

###

Co-authors of this study include: Stacey L. Kolar, Juan Torres, Xuemo Fan, Cedars-Sinai; Chih-Ming Tsai, Cedars-Sinai and UC San Diego; and Huiying Li, UCLA.

Media Contact

Heather Buschman, PhD

[email protected]