Understanding the origins of extremely oblique orbital angles such as these could help reveal details about the planetary formation process

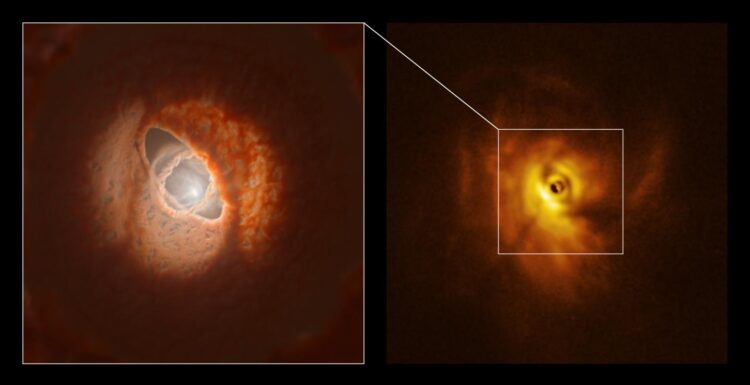

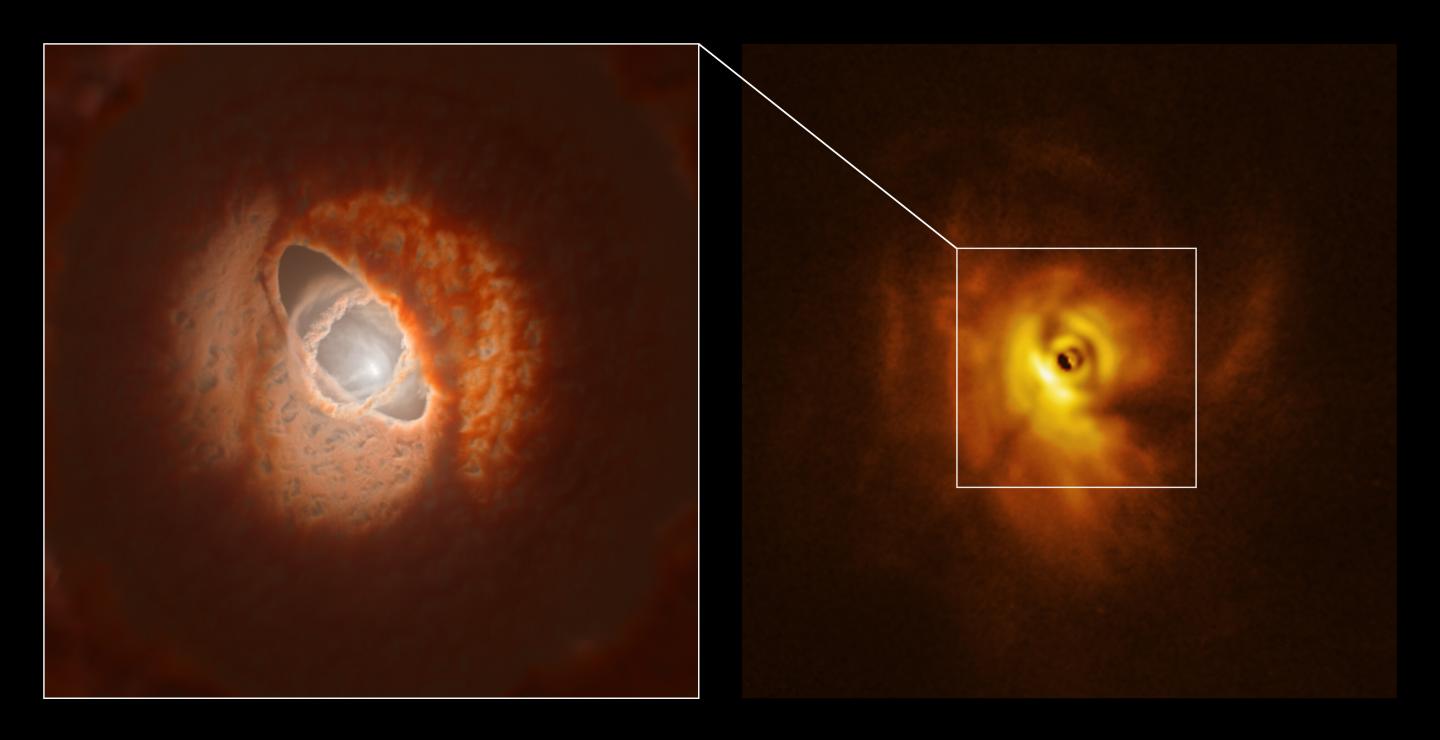

Credit: Credit: ESO/L. Calçada, Exeter/Kraus et al.

Washington, DC– The discovery that our galaxy is teeming with exoplanets has also revealed the vast diversity of planetary systems out there and raised questions about the processes that shaped them. New work published in Science by an international team including Carnegie’s Jaehan Bae could explain the architecture of multi-star systems in which planets are separated by wide gaps and do not orbit on the same plane as their host star’s equatorial center.

“In our Solar System, the eight planets and many other minor objects orbit in a flat plane around the Sun; but in some distant systems, planets orbit on an incline–sometimes a very steep one,” Bae explained. “Understanding the origins of extremely oblique orbital angles such as these could help reveal details about the planetary formation process.”

Stars are born in nurseries of gas and dust called molecular clouds–often forming in small groups of two or three. These young stars are surrounded by rotating disks of leftover material, which accretes to form baby planets. The disk’s structure will determine the distribution of the planets that form from it, but much about this process remains unknown.

Led by University of Exeter’s Stefan Kraus, the team found the first direct evidence confirming the theoretical prediction that gravitational interactions between the members of multi-star systems can warp or break their disks, resulting in misaligned rings surrounding the stellar hosts.

Over a period of 11 years, the researchers made observations of the the GW Orionis triple-star system, located just over 1,300 light-years away in the Orion constellation. Their work was accomplished using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array–a radio telescope made up of 66 antennas.

“Our images reveal an extreme case where the disk is not flat at all, but is warped and has a misaligned ring that has broken away from the disk,” Kraus said.

Their findings were tested by simulations, which demonstrated that the observed disorder in the orbits of the three stars could have caused the disk to fracture into the distinct rings.

“We predict that many planets on oblique, wide-separation orbits will be discovered in future planet imaging campaigns,” said co-author Alexander Kreplin, also of the University of Exeter.

Bae concluded: “This system is a great example of how theory and observing can inform each other. I’m excited to see what we learn about this system and others like it with additional study.”

###

Support for this research was provided by the European Research Council under the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 program Seventh Framework program; the Science Technology and Facilities Council; the U.S. NSF; NASA; the research council of the KU Leuven; and the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Media Contact

Jaehan Bae

[email protected]