Credit: Hollander, et al, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2019.

PITTSBURGH, Oct. 30, 2019 – Physicians who received gifts from pharmaceutical companies related to opioid medications were more likely to prescribe opioids to their patients the following year, compared to physicians who did not receive such gifts, according to a new analysis led by health policy scientists at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

The research, published today in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, is the first to apply robust statistical analysis methods in examining the relationship between gift-giving and opioid prescribing by medical specialty, as well as by pharmaceutical company.

“For every 100 Americans, there were 58 opioid prescriptions written in 2017 — that is a tremendous amount of prescribing in a country that is struggling with an opioid epidemic,” said lead author Mara Hollander, a doctoral student in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Health Policy and Management. “Our research points to a potential motivator behind this prescribing that could be reduced through policy interventions.”

Federal law mandates that pharmaceutical companies report the dollar value of physician gift-giving, which includes meals, travel and lodging, education, consulting fees and honoraria, and “compensation for services other than consulting,” alongside any product the company promotes in association with the gift.

Hollander and her research team used a Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services database to get information on gifts given to physicians in 2014 and 2015 by pharmaceutical and medical device companies related to promotion of opioid medications. They matched that data with Medicare data on physician prescribing of opioids in 2015 and 2016. This allowed the team to see if physicians who received gifts were more likely to prescribe opioids the following year, and if there was a link between the dollar value of the gifts and the level of prescribing. Ultimately, 236,103 physicians were included in the study.

The team then took the analysis a step further and grouped the physicians into seven broad specialty categories: primary care, surgery, psychiatry and neurology, rehabilitative and sports medicine, hematology and oncology, pain medicine and anesthesiology, and other non-surgical specialties, to see if the link between gifts and prescribing differed based on medical specialty.

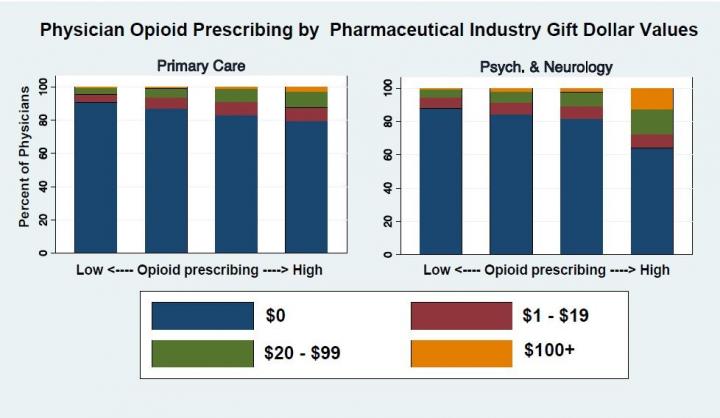

While there was a relationship between gifts and opioid prescribing in all specialties, there was considerable variability. Primary care physicians were 3.5 times as likely to be in the highest quartile of opioid prescribing if they were paid $100 or more in gifts. Psychiatrists and neurologists who were paid $100 or more were 13 times as likely to be in the highest quartile of opioid prescribing compared to their counterparts who received less.

When the team further examined the companies behind the gifts, they found that, while 18 different companies provided gifts related to opioids, two companies — Insys and Purdue — were responsible for nearly two-thirds of the value of those gifts. Both have settled lawsuits for hundreds of millions of dollars related to opioid promotion and Purdue stopped marketing opioids to physicians in 2018. However, there was great heterogeneity in which companies were marketing to which specialties — for example, Mallinckrodt was responsible for 3% of opioid-related gifts to physicians overall, but more than half of the value of gifts to surgeons came from that company, indicating that Mallinckrodt likely targeted surgeons.

“I would encourage policymakers and state and federal health officials to really dig into these findings and develop interventions that address this relationship between pharmaceutical company gift-giving and opioid prescribing,” said senior author Marian Jarlenski, Ph.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of health policy and management at Pitt Public Health. “The opioid epidemic is nowhere close to being over. Yes, in the past year we’ve seen a leveling off in the rate of overdose deaths, but that masks the huge number of people living with opioid use disorder and the impact that high rates of opioid prescribing continue to have.”

###

Additional authors on this research are Julie M. Donohue, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Krans, M.D., M.Sc., both of Pitt; and Bradley D. Stein, M.D., Ph.D., of RAND Corporation.

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA045675.

To read this release online or share it, visit https:/

About the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health

The University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, founded in 1948 and now one of the top-ranked schools of public health in the United States, conducts research on public health and medical care that improves the lives of millions of people around the world. Pitt Public Health is a leader in devising new methods to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases, HIV/AIDS, cancer and other important public health problems. For more information about Pitt Public Health, visit the school’s Web site at http://www.

http://www.

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Office: 412-647-9975

Mobile: 412-559-2431

E-mail: [email protected]

Contact: Ashley Trentrock

Office: 412-586-9776

Mobile: 412-529-9092

E-mail: [email protected]

Media Contact

Allison Hydzik

[email protected]

412-647-9975