An ongoing research project into the impact of offshore windfarm electromagnetic fields on shark development reveals that the alternating electric currents produced by underwater windfarm cables seems not to disrupt the growth or survival of sharks.

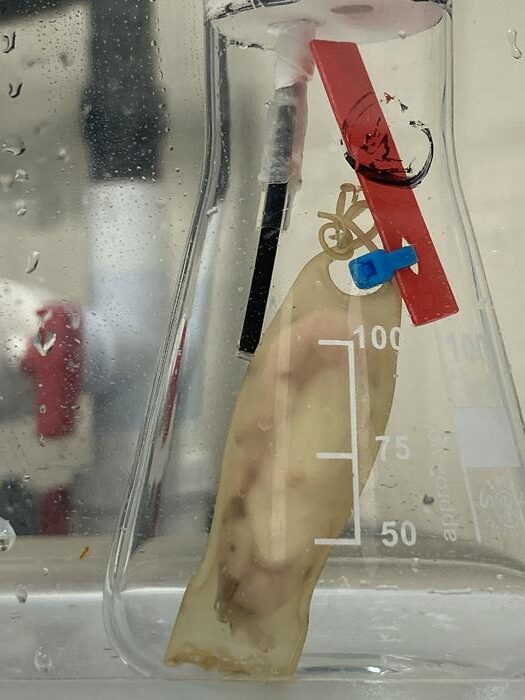

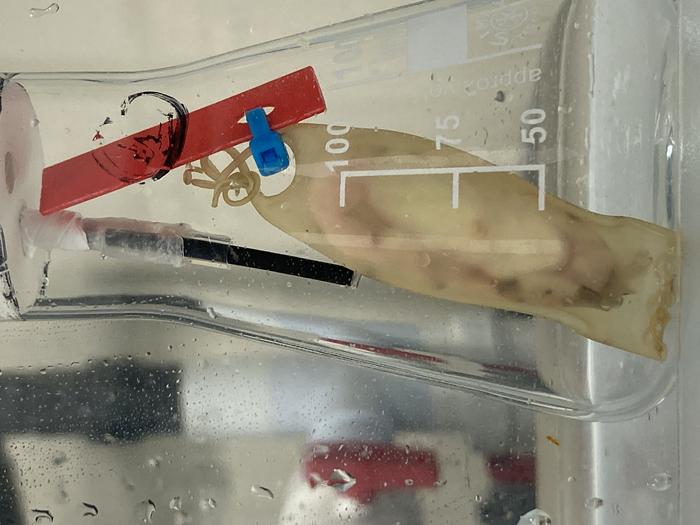

Credit: Julie Lucas

An ongoing research project into the impact of offshore windfarm electromagnetic fields on shark development reveals that the alternating electric currents produced by underwater windfarm cables seems not to disrupt the growth or survival of sharks.

Offshore windfarms are one of the most common marine renewable energy (MRE) producers, and are seen as a pivotal technology in the global transition towards renewable energy and away from fossil fuels that contribute to climate change.

However, their proliferation in marine environments raises new questions about their impacts on wildlife. Energy operators and researchers are working together to understand the effects of these increasingly prevalent technologies.

“Wind farms can induce noise, vibrations, interruptions to ecological continuity and generate electromagnetic fields at the level of submarine electric cable,” says Dr Julie Lucas, a research associate at France’s National Museum of Natural History. “They can affect behaviour of electro-sensitive species which use natural electromagnetic fields to move and feed, such as sharks.”

These offshore windfarms rely on submarine electric cables (CES) that use either alternating current (AC) or direct current (DC) depending on their function, power output and cable length. “Currently, wind farms located less than 50km from the coast use AC current, whereas more powerful future wind farms are planned to be located more than 50 km away and will use DC current,” says Dr Lucas.

Both AC and DC currents produce strong magnetic fields into the water surrounding them. “These magnetic fields can affect the behaviour of electro- and magneto-sensitive species such as elasmobranchs, which use natural electromagnetic fields to move and feed,” says Dr Lucas. “The increasing number of offshore wind farms is likely to amplify these effects, while existing information on their impact on marine communities remains patchy.”

Dr Lucas’ study aims to identify the effects of the magnetic fields caused by AC and DC currents on the survival, development and behaviour of sharks and other electro-sensitive elasmobranchs. “The results will enable us to understand how elasmobranchs react to electromagnetic fields,” says Dr Lucas.

Dr Lucas and her team studied two key life stages of the small-spotted catshark (Scyliorhinus canicular), embryo and juvenile, under either control or windfarm-impacted conditions using AC or DC currents. They recorded daily survival, weekly development and growth and metabolic rate through respirometry for both life stages.

“Thankfully, preliminary results suggest that the impact of alternating electromagnetic fields seem to be limited on the factors that we have measured,” says Dr Lucas. However, the full results are still being analysed and the effects of DC current will be investigated later this year.

“The results of this project will make it possible to understand more precisely how sharks react to electromagnetic fields depending on their intensity and the type of current,” says Dr Lucas. “They will also improve our knowledge of the impacts of MREs on marine species.”

Dr Lucas hopes that this research can help inform policy to protect marine species and determine what improvements can be made to CES to continue limiting their impact. “This project will provide essential information for managers and decision-makers to meet the challenges of developing MREs without harming marine biodiversity,” says Dr Lucas.

This research is being presented at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Conference in Prague on the 2-5th July 2024.