Researchers identify the 100 transnational corporations extracting the majority of revenues from economic use of the world’s ocean

Credit: Science Advances

For the first time, scientists have identified the 100 transnational corporations (see table) extracting the majority of revenues from economic use of the world’s ocean.

Dubbed the “Ocean 100”, the group of companies generated US$1.1 trillion in revenues in 2018, according to the research published in the journal Science Advances.

“If the Ocean 100 was a country it would be the 16th largest on Earth,” said Henrik Österblom, a co-author on the study from Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University. “By revenue, the Ocean 100 is equivalent to the GDP of Mexico.”

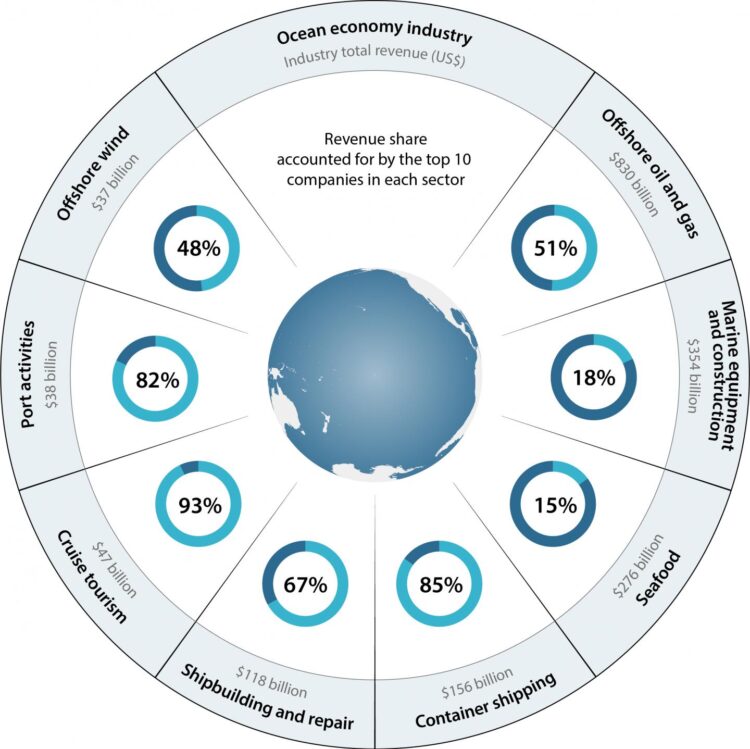

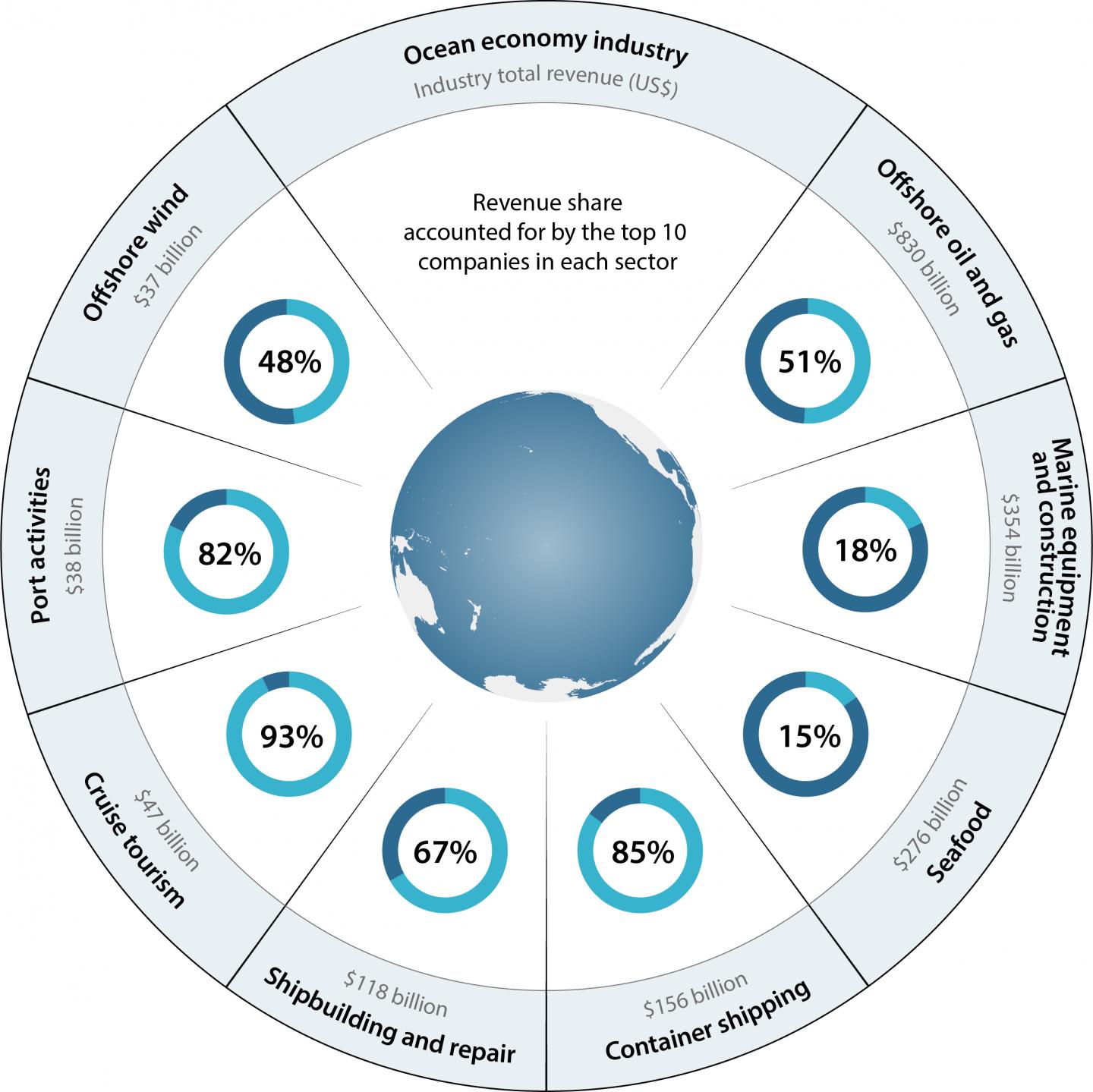

The researchers from the centre and Duke University assessed eight core ocean industries: offshore oil and gas, marine equipment and construction, seafood production and processing, container shipping, shipbuilding and repair, cruise tourism, port activities and offshore wind. Combined these industries had revenues of $1.9 trillion in 2018, the most recent year analysed. According to the study, the 100 largest companies took an estimated 60% of all revenues in these eight industries.

The Ocean 100 list is dominated by offshore oil and gas companies with a combined revenue of $830 billion. The only non-oil and gas company in the top ten is the shipping company A.P. Møller-Mærsk at No. 9.

The researchers found a consistent pattern across all eight industries. A a small number of companies account for the bulk of revenues. On average, the 10 largest companies in each industry took 45 percent of that industry’s total revenue. The highest concentrations were found in cruise tourism (93 percent), container shipping (85 percent) and port activities (82 percent).

“Now that we know who has the biggest impact on the ocean this can help improve transparency relating to sustainability and ocean stewardship,” said lead author John Virdin from Duke University.

“Why do such a small number of companies dominate this sector? This likely reflects high barriers to entry in the ocean economy. A lot of expertise and capital are needed to operate in the sea, both for the established industries and emerging one such as deep-sea mining and marine biotechnology,” said Virdin.

The authors say that such high concentration is a risk to international goals for sustainable ocean use, but possibly also an opportunity. One risk is that a small number of companies headquartered in a few countries (by revenue, the largest companies are based in the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, France, the United Kingdom and Norway) could more easily lobby governments to weaken social or environmental rules for example to limit greenhouse gas emissions or stifle innovation. Conversely, with just a small number of companies it may be easier to coordinate action for ocean stewardship and harness private funding to support globally-agreed public initiatives in the ocean (e.g. ocean clean-ups, conservation, support for small-scale fishing communities).

One surprise in the study is the scale of offshore wind farms. This is now becoming a major sector in the ocean economy worth $37 billion in 2018 – and growing rapidly. “Since 2000, the capacity of offshore wind farms has seen a staggering 400-fold increase and this is expected to accelerate further as demand for renewable energy grows,” said Jean Baptiste Jouffray, a co-author of the study from the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

The idea for the new analysis began four years back while John Virdin was providing advice for governments on the future of the ocean economy.

“The OECD had just published a report on the future of the ocean economy which included more clearly defined economic sectors. Around this time, someone handed me Henrik and Jean Baptiste’s 2015 paper on keystone actors in the seafood industry. I wondered if we could apply the same keystone actor concept to the entire ocean economy using the OECD definitions,” said Virdin.

The analysis did not explore the ecological impact of the Ocean 100. Future research will explore the Ocean 100 environmental footprint with a focus on carbon emissions.

###

The research contributes to UNESCO’s Decade of Ocean Science (2021-2030).

Largest corporations by revenue in the ocean economy

Corporation:

- 1. Saudi Aramco

2. Petrobras

3. National Iranian Oil Company

4. Pemex

5. ExxonMobil

6. Royal Dutch Shell

7. Equinor

8. Total

9. A.P. Møller-Maersk

10. BP

11. Qatar Petroleum

12. Chevron

13. China National Offshore Oil Corporation

14. Abu Dhabi National Oil Company

15. Mediterranean Shipping Company

16. CMA CGM

17. Petoro

18. Eni S.p.A.

19. Carnival Corporation & plc

20. Petronas

21. Oil and Natural Gas Corporation

22. China State Shipbuilding Corp Ltd

23. COSCO Shipping

24. Hyundai Engineering and Construction

25. TechnipFMC

26. Hyundai Heavy Industries

27. Hapag-Lloyd

28. Ocean Network Express

29. Saipem

30. Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd.

31. Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Equipment

32. Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation

33. General Dynamics

34. Huntington Ingalls Industries

35. State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic

36. Sonangol

37. Maruha Nichiro Corporation

38. ConocoPhillips

39. Vår Energi

40. Inpex

41. China Shipbuilding Industry Company Ltd

42. Fincantieri Group

43. PTT Exploration and Production Public Company

44. Nippon Suisan Kaisha

45. Pertamina

46. Sinopec Group

47. Wartsila

48. Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings

49. DP World

50. Shanghai International Port Group

51. Evergreen Marine Corporation

52. BHP

53. Occidental Petroleum

54. Repsol

55. Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.

56. Dongwon Enterprise

57. Wintershall Dea

58. Samsung Heavy Industries

59. Ørsted

60. Mowi

61. Yang Ming Marine Transport

62. Pacific International Lines

63. CK Hutchison Holdings

64. Naval Group

65. APM Terminals

66. Thai Union Group

67. Subsea 7

68. Perenco

69. PetroVietnam

70. Lukoil

71. BAE Systems

72. Chrysaor

73. Bahrain Petroleum Company

74. Aker BP

75. Hyundai Merchant Marine

76. Sembcorp Marine

77. Dragon-ENOC

78. Mubadala Development Company

79. Mitsubishi Corporation

80. Hitachi Zosen

81. Imabari Shipbuilding

82. Gazprom

83. Yangzijiang Shipbuilding (Holdings) Ltd

84. Zim

85. MSC Cruises

86. Dredging, Environmental and Marine Engineering

87. PSA International

88. Mitsui

89. Royal Boskalis Westminster

90. OUG Holdings

91. Aker Solutions ASA

92. Neptune Energy

93. Austevoll Seafood

94. OMV

95. Hess

96. Woodside

97. Meyer Neptun

98. Suncor Energy

99. Spirit Energy

100. Trident Seafoods

Publication

CITATION: “The Ocean 100: Transnational Corporations in the Ocean Economy,” J. Virdin, T. Vegh, J.B. Jouffray, R. Blasiak, S. Mason, H. Österblom, D. Vermeer, H. Wachtmeister and N. Werner. Jan. 13, 2021, Science Advances.

Paper available on request.

Graphics and table available on request.

Media Contact

Owen Gaffney

[email protected]