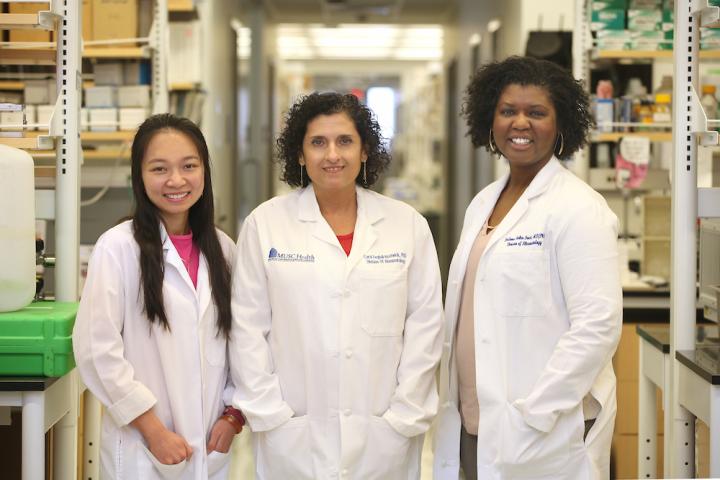

Biomedical science students in a translational science training program at the Medical University of South Carolina shadow clinicians to learn more about the patients whose diseases they study.

Credit: Sarah Pack, Medical University of South Carolina

Translational research aims to speed research breakthroughs into the clinic. And yet, training for basic scientists and clinicians too often remains siloed, leading to divergent cultures and a loss of opportunity for cross-disciplinary collaboration.

The South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute’s TL1 program, a translational research training program for doctoral students in the MUSC Colleges of Graduate Studies, Medicine, Health Professions, Dental Medicine, and Pharmacy, is trying to change that by requiring TL1 trainees to complete a rotation in which they shadow physicians who treat patients with the diseases at the center of their research. The rotation, dubbed the Translational Sciences Clinic, is profiled in a recent article in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science (JCTS).

“The education provided by the Translational Sciences Clinic is a two-way street. It provides basic science trainees a better understanding of what the patients’ problems are and what they need to address in their research,” explained TL1 program director and lead author Perry Halushka, M.D., Ph.D. “But the students also educate the clinicians by bringing basic science questions and answers to the patients’ problems.”

In the third year of their graduate studies, students spend a half day each week in the clinics of their choice. By that time, they are already well versed in teamwork and in the various stages of translational research through their participation in the TL1 journal club, as was detailed in another recent JCTS article. In journal club, they read articles documenting the successful translation of a breakthrough to the clinic and work in teams of three to present each step of that research. One member discusses the fundamental basic research; another, the clinical testing of the breakthrough; and the third, its dissemination.

“The TL1 journal club helps students see how a basic discovery can be developed into a drug or a device,” said TL1 associate director and senior author Carol Feghali-Bostwick, Ph.D. “It has the additional advantage of having them work as teams.”

This background prepares them well to work on cross-disciplinary teams in the Translational Sciences Clinic. In turn, the rotation in the clinic often leads to ongoing cross-disciplinary collaborations.

The clinicians that the trainees shadow often join their mentorship teams and provide clinical perspectives on their research. Sometimes, they even serve on their dissertation committees. Such was the case with Daniel Lench, who has now graduated from the program. He worked with Gonzalo J. Revuelta, D.O., a movement disorders specialist.

“Working with Dr. Revuelta in a translational research setting was a uniquely rewarding experience,” said Lench. “I spent one semester in his movement disorder clinic observing and learning from specific cases. As a member of my dissertation committee, Dr. Revuelta helped me think more about the clinical relevance of research questions. Overall, my time in the clinic with him provided a strong framework on how to perform translational research in the future.”

In some cases, the clinician mentor is a SCTR KL2 scholar, a junior-level physician-scientist who is guaranteed time to pursue a research project. For example, Xinh Xinh Nguyen, a TL1 trainee who studies scleroderma in Feghali-Bostwick’s research laboratory, was able to shadow Deanna Baker Frost, M.D., Ph.D., a KL2 scholar and rheumatologist with a clinical interest in autoimmune diseases and fibrosis, as she saw patients with scleroderma.

“Participation in the TL1 program has provided me with additional learning opportunities to gain expertise in translational research,” says Nguyen. “It has enhanced my knowledge about clinically relevant aspects of my project.””

Feghali-Bostwick recognizes how greatly the rotation in the Translational Sciences Clinic benefited Nguyen.

“Xinh Xinh is doing research on scleroderma, but now she understands better what scleroderma is and understands what patients go through and what their complications are and what they come in for,” explained Feghali-Bostwick. “That puts it all in perspective and helps her better understand why she is doing the research she is doing.”

Feghali-Bostwick believes that there is a natural mentoring relationship between the KL2 and TL1 scholars. “There is less of a gap between them than between senior scientists, like myself, and TL1s,” she said. “It’s a good fit; it’s a natural fit.”

Most of all, the Translational Sciences Clinic motivates trainees and reminds them of the importance of the work they do. On program evaluations, many comment that their time spent in clinic seeing patients was among their most meaningful and inspiring experiences in graduate school.

“Through the time spent in the Translational Research Clinic, trainees suddenly get a greater appreciation for what they’re doing at the bench and see how that could change people’s lives,” said Halushka. “They can actually see what happens when fundamental discoveries are turned into new therapeutic approaches.”

###

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) is the oldest medical school in the South, as well as the state’s only integrated, academic health sciences center with a unique charge to serve the state through education, research and patient care. Each year, MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and nearly 800 residents in six colleges: Dental Medicine, Graduate Studies, Health Professions, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. The state’s leader in obtaining biomedical research funds, in fiscal year 2019, MUSC set a new high, bringing in more than $284 million. For information on academic programs, visit musc.edu.

As the clinical health system of the Medical University of South Carolina, MUSC Health is dedicated to delivering the highest quality patient care available, while training generations of competent, compassionate health care providers to serve the people of South Carolina and beyond. Comprising some 1,600 beds, more than 100 outreach sites, the MUSC College of Medicine, the physicians’ practice plan, and nearly 275 telehealth locations, MUSC Health owns and operates eight hospitals situated in Charleston, Chester, Florence, Lancaster and Marion counties. In 2019, for the fifth consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report named MUSC Health the No. 1 hospital in South Carolina. To learn more about clinical patient services, visit muschealth.org.

MUSC and its affiliates have collective annual budgets of $3.2 billion. The more than 17,000 MUSC team members include world-class faculty, physicians, specialty providers and scientists who deliver groundbreaking education, research, technology and patient care.

About the SCTR Institute

The South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research (SCTR) Institute is the catalyst for changing the culture of biomedical research, facilitating sharing of resources and expertise and streamlining research-related processes to bring about large-scale change in the clinical and translational research efforts in South Carolina. Our vision is to improve health outcomes and quality of life for the population through discoveries translated into evidence-based practice. To learn more, visit https:/

Media Contact

Heather Woolwine

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.