In experiments with worms, researchers showed that epigenetic marks on sperm chromosomes affect gene expression and development in offspring

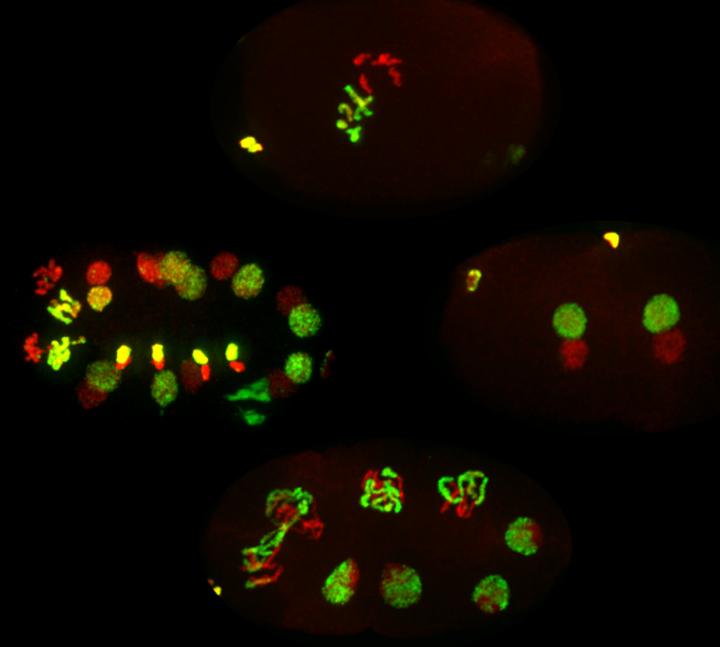

Credit: K. Kaneshiro

As an organism grows and responds to its environment, genes in its cells are constantly turning on and off, with different patterns of gene expression in different cells. But can changes in gene expression be passed on from parents to their children and subsequent generations? Although indirect evidence for this phenomenon, called “transgenerational epigenetic inheritance,” is growing, it remains controversial because the mechanisms behind it are so mysterious.

Now researchers at UC Santa Cruz have demonstrated that epigenetic information carried by parental sperm chromosomes can cause changes in gene expression and development in the offspring. Their study, published March 20 in Nature Communications, involved a series of clever experiments using the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans.

Epigenetic changes do not alter the DNA sequences of genes, but instead involve chemical modifications to either the DNA itself or to the histone proteins with which DNA is packaged in the chromosomes. These modifications or “marks” change gene expression, turning genes on or off.

In their experiments with C. elegans, researchers in Susan Strome’s lab at UC Santa Cruz have focused on histone marks, modifications to specific amino acids in the tails of histone proteins. Strome, a professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology, said the new study addressed a central question in the field of epigenetics.

“It’s a very direct question: Does inheriting sperm chromosomes with altered histone packaging of the DNA affect gene expression in the offspring? And the answer is yes,” she said.

First author Kiyomi Kaneshiro, a graduate student in Strome’s lab who led the study, said C. elegans is a good model for studying this question because histone packaging is fully retained in the worm’s sperm chromosomes. In humans and other mammals, histone packaging is only partially retained in sperm.

“There is debate over how much histone packaging is retained in humans, but we know it is retained in some developmentally important regions of the genome,” Kaneshiro said.

Researchers have focused on epigenetic inheritance in the paternal line because the sperm contributes little more than its chromosomes to the embryo. The egg contains many other components that may influence the development of the embryo, making it harder to tease out epigenetic effects in the maternal line.

In her experiments, Kaneshiro selectively removed a specific histone mark from sperm chromosomes, then fertilized eggs with the modified sperm and studied the resulting offspring. A crucial innovation was to use sperm and eggs from two different strains of C. elegans, which enabled Kaneshiro to distinguish between the chromosomes inherited from the sperm and those inherited from the egg. She chose worm strains from Britain and Hawaii that had evolved separately long enough to accumulate many small genetic differences (called single nucleotide polymorphisms).

“The dads were British and the moms were Hawaiian, and there are enough differences between them that we could distinguish between the two parental genomes in the cells of their offspring,” Kaneshiro said. “Through this hybrid system, we were able to see differences in gene expression that were a direct result of the changes in histone marks on the sperm chromosomes.”

Furthermore, those changes in gene expression had developmental consequences. With removal of the histone marks, the sperm chromosomes lost a repressive signal that normally keeps certain genes from being active in the offspring’s germline (the cells that give rise to eggs and sperm). Kaneshiro observed that the offspring’s germline cells turned on neuronal genes and began developing into neurons.

The particular histone mark removed in these experiments is a widely studied epigenetic mark found in animals ranging from worms to fruit flies to humans. “This mark is found on the histones that are retained on sperm chromosomes in humans,” Kaneshiro said.

The new findings show that inherited epigenetic marks affect gene expression and development. But the study involved artificially changing the marks on the sperm chromosomes. What remains to be understood is how environmental effects on an adult organism could alter epigenetic marks in its germline cells, making it possible for those environmental effects to be transmitted to subsequent generations.

“Our findings raise the possibility that histone marks are carriers for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance,” Kaneshiro said. “We know that the environment an organism experiences can change gene expression patterns in somatic cells [non-germline body cells]. If it changes gene expression patterns in the germline, we expect that those changes can be inherited, but we haven’t shown that yet.”

###

In addition to Kaneshiro and Strome, the coauthors of the study include Andreas Rechtsteiner, a bioinformaticist in Strome’s lab. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

Tim Stephens

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.