Credit: FridoFoe

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Buried deep within the dazzlingly intricate machinery of the human cell could lie a key to treating a range of deadly cancers, according to a team of scientists at Florida State University.

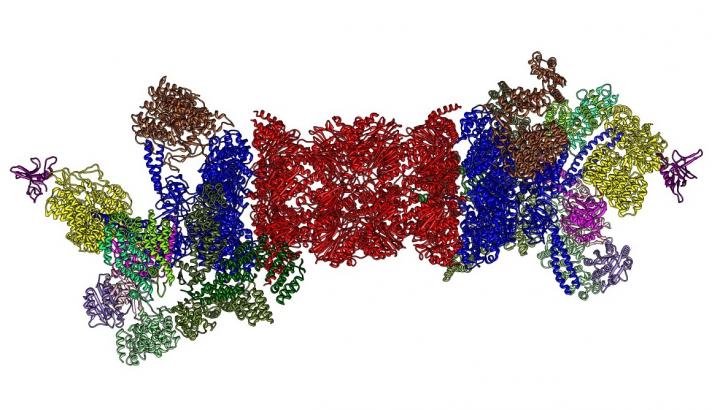

In a new study, researchers discovered a critical missing step in the production of proteasomes — tiny structures in a cell that dispose of protein waste — and found that carefully targeted manipulation of this step could prove an effective recourse for the treatment of cancer.

Their findings were published in the journal Cell Reports.

“Proteasomes are kind of like the cell’s recycling center for proteins,” said study co-author Robert Tomko, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences in FSU’s College of Medicine. “Typically, proteins inside the cell are produced to fulfill a certain function, and once that function is fulfilled, they are no longer needed and need to be removed.”

Proteasomes collect those unneeded, damaged or defective proteins and decompose them into amino acid building blocks, which are subsequently repurposed for the production of new proteins. Proteasomes are assembled from more than 60 protein subunits, “however, they don’t just form spontaneously from these parts,” Tomko said.

“They require assistance from dedicated helper proteins called assembly chaperones,” he said. “These chaperones act as factory workers to build proteasomes. Once the proteasome is built, the chaperones have to release it so that it can function properly and they can then begin work on the next one.”

It’s this stage of the assembly process — the chaperone’s release of the fully completed proteasome — that interested Tomko and his team. Before their study, the signaling mechanisms responsible for triggering the release of assembled proteasomes was a mystery, limiting scientists’ understanding of the critical final phase of proteasome assembly.

Tomko’s group found that the answer to this puzzle has to do with a strange feat of molecular contortion. When a proteasome is nearly finished assembling, it temporarily changes its shape, making room for the chaperone protein as the proteasome’s final building blocks are linked together. When assembly is complete, the proteasome suddenly snaps back into its original shape, crowding out the chaperone protein and eventually popping it entirely free.

“This finding explains how this seemingly impossible process happens, and importantly, it suggests that by controlling it, we could regulate proteasome assembly to help treat certain types of cancers,” Tomko said.

Cancer cells, just like healthy cells, rely on proteasomes to collect and dispense with toxic proteins. Because cancer cells produce large amounts of damaged proteins, they compensate by overproducing proteasome assembly chaperones, which build more proteasomes to meet the cancer cells’ needs. These fleets of diligent proteasome cleanup crews keep the cancer cells from self-destructing and allow them to propagate more effectively.

In addition, the specific chaperone protein Tomko and his team studied, called gankyrin, is an oncogene — a piece of genetic material that is present at elevated levels in some tumors and has been shown to promote cancer growth.

Tomko said that if scientists can devise a way of interfering with the “popping off” of gankyrin chaperone proteins from assembling proteasomes, they may be able to mitigate the cancer-causing effects of gankyrin while also condemning harmful cancer cells to death by their own toxic proteins.

“First, we can trap gankyrin and prevent it from performing its pro-cancer functions,” he said. “Second, by trapping gankyrin and preventing completion of proteasome assembly, we can sensitize these cancer cells to the toxic, damaged proteins they are already overproducing. Gankyrin is important for several types of cancer, including liver, colon and cervical, so this approach might help to treat cancers of multiple organ types.”

The next step, Tomko said, is to confirm that trapping gankyrin is toxic to cancer cells but nontoxic to healthy cells. If this is found to be the case, he and his team could begin developing candidate drugs for preclinical testing.

###

Tomko and FSU researcher Antonia Nemec spearheaded the study, with additional contributions from graduate students Randi Reed and Jennifer Warnock and FSU researcher Anna Peterson. The research was funded by the Florida State University College of Medicine and The National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

Zachary Boehm

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.