MIT researchers and their colleagues have developed a new computational model of the human brain's face-recognition mechanism that seems to capture aspects of human neurology that previous models have missed.

The researchers designed a machine-learning system that implemented their model, and they trained it to recognize particular faces by feeding it a battery of sample images. They found that the trained system included an intermediate processing step that represented a face's degree of rotation — say, 45 degrees from center — but not the direction — left or right.

This property wasn't built into the system; it emerged spontaneously from the training process. But it duplicates an experimentally observed feature of the primate face-processing mechanism. The researchers consider this an indication that their system and the brain are doing something similar.

"This is not a proof that we understand what's going on," says Tomaso Poggio, a professor of brain and cognitive sciences at MIT and director of the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines (CBMM), a multi-institution research consortium funded by the National Science Foundation and headquartered at MIT. "Models are kind of cartoons of reality, especially in biology. So I would be surprised if things turn out to be this simple. But I think it's strong evidence that we are on the right track."

Indeed, the researchers' new paper includes a mathematical proof that the particular type of machine-learning system they use, which was intended to offer what Poggio calls a "biologically plausible" model of the nervous system, will inevitably yield intermediary representations that are indifferent to angle of rotation.

Poggio, who is also a primary investigator at MIT's McGovern Institute for Brain Research, is the senior author on a paper describing the new work, which appeared today in the journal Computational Biology. He's joined on the paper by several other members of both the CBMM and the McGovern Institute: first author Joel Leibo, a researcher at Google DeepMind, who earned his PhD in brain and cognitive sciences from MIT with Poggio as his advisor; Qianli Liao, an MIT graduate student in electrical engineering and computer science; Fabio Anselmi, a postdoc in the IIT@MIT Laboratory for Computational and Statistical Learning, a joint venture of MIT and the Italian Institute of Technology; and Winrich Freiwald, an associate professor at the Rockefeller University.

Emergent properties

The new paper is "a nice illustration of what we want to do in [CBMM], which is this integration of machine learning and computer science on one hand, neurophysiology on the other, and aspects of human behavior," Poggio says. "That means not only what algorithms does the brain use, but what are the circuits in the brain that implement these algorithms."

Poggio has long believed that the brain must produce "invariant" representations of faces and other objects, meaning representations that are indifferent to objects' orientation in space, their distance from the viewer, or their location in the visual field. Magnetic resonance scans of human and monkey brains suggested as much, but in 2010, Freiwald published a study describing the neuroanatomy of macaque monkeys' face-recognition mechanism in much greater detail.

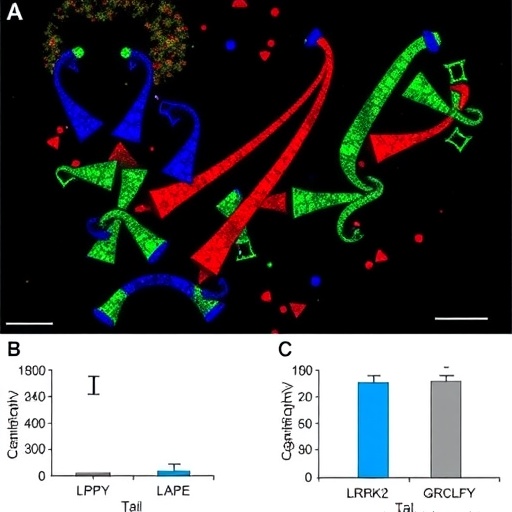

Freiwald showed that information from the monkey's optic nerves passes through a series of brain locations, each of which is less sensitive to face orientation than the last. Neurons in the first region fire only in response to particular face orientations; neurons in the final region fire regardless of the face's orientation — an invariant representation.

But neurons in an intermediate region appear to be "mirror symmetric": That is, they're sensitive to the angle of face rotation without respect to direction. In the first region, one cluster of neurons will fire if a face is rotated 45 degrees to the left, and a different cluster will fire if it's rotated 45 degrees to the right. In the final region, the same cluster of neurons will fire whether the face is rotated 30 degrees, 45 degrees, 90 degrees, or anywhere in-between. But in the intermediate region, a particular cluster of neurons will fire if the face is rotated by 45 degrees in either direction, another if it's rotated 30 degrees, and so on.

This is the behavior that the researchers' machine-learning system reproduced. "It was not a model that was trying to explain mirror symmetry," Poggio says. "This model was trying to explain invariance, and in the process, there is this other property that pops out."

Neural training

The researchers' machine-learning system is a neural network, so called because it roughly approximates the architecture of the human brain. A neural network consists of very simple processing units, arranged into layers, that are densely connected to the processing units — or nodes — in the layers above and below. Data are fed into the bottom layer of the network, which processes them in some way and feeds them to the next layer, and so on. During training, the output of the top layer is correlated with some classification criterion — say, correctly determining whether a given image depicts a particular person.

In earlier work, Poggio's group had trained neural networks to produce invariant representations by, essentially, memorizing a representative set of orientations for just a handful of faces, which Poggio calls "templates." When the network was presented with a new face, it would measure its difference from these templates. That difference would be smallest for the templates whose orientations were the same as that of the new face, and the output of their associated nodes would end up dominating the information signal by the time it reached the top layer. The measured difference between the new face and the stored faces gives the new face a kind of identifying signature.

In experiments, this approach produced invariant representations: A face's signature turned out to be roughly the same no matter its orientation. But the mechanism — memorizing templates — was not, Poggio says, biologically plausible.

So instead, the new network uses a variation on Hebb's rule, which is often described in the neurological literature as "neurons that fire together wire together." That means that during training, as the weights of the connections between nodes are being adjusted to produce more accurate outputs, nodes that react in concert to particular stimuli end up contributing more to the final output than nodes that react independently (or not at all).

This approach, too, ended up yielding invariant representations. But the middle layers of the network also duplicated the mirror-symmetric responses of the intermediate visual-processing regions of the primate brain.

###

Additional background

ARCHIVE: Machines that learn like people

ARCHIVE: More-flexible machine learning

ARCHIVE: Artificial-intelligence research revives its old ambitions

ARCHIVE: How the brain recognizes objects

Media Contact

Abby Abazorius

[email protected]

617-253-2709

@MIT

http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag