The research group, led by Dr. Christina Scheel, developed an assay whereby cultured human breast epithelial cells rebuild the three-dimensional tissue architecture of the mammary gland.

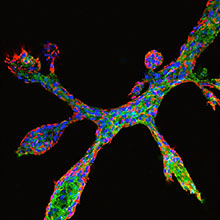

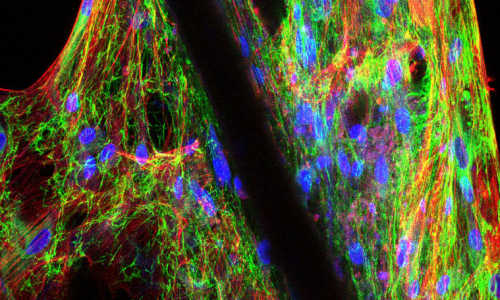

Detail of breast epithelial cells in culture undergoing ductal elongation and side-branching. Image: Haruko Miura. Copyright: HMGU

For this purpose, a transparent gel is used in which cells divide and spread, similar to the developing mammary gland during puberty. Specifically, cells divide and generate hollow ducts that form a network of branches and terminate in grape-like structures. Throughout the reproductive lifespan of a woman, the mammary gland is constantly remodeled and renewed in order to guarantee milk production even after multiple pregnancies. Although their exact identity remains elusive, this high cellular turnover requires the presence of cells with regenerative capacity, i.e. stem cells. Breast cancer cells can adopt properties of stem cells to acquire aggressive traits. To determine how aggressive traits arise in breast cancer cells, it is therefore crucial to first elucidate the functioning of normal breast stem cells. For this purpose, the Scheel group provides a new powerful experimental tool.

A technological break-through

Using their newly developed organoid assay, the researchers observed that the behaviour of cells with regenerative capacity is determined by the physical properties of their environment. Jelena Linnemann, first author of the study, explains: “We were able to demonstrate that increasing rigidity of the gel led to increased spreading of the cells, or, said differently, invasive growth. Similar behaviour was already observed in breast cancer cells. Our results suggest that invasive growth in response to physical rigidity represents a normal process during mammary gland development that is exploited during tumor progression.” Co-author Lisa Meixner adds that “with our assay, we can elucidate how such processes are controlled at the molecular level, which provides the basis for developing therapeutic strategies to inhibit them in breast cancer.”

Another reason the mini-mammary glands represent a particularly valuable tool is, because the cells that build these structure are directly isolated from patient tissue. In this case, healthy tissue from women undergoing aesthetic breast reduction is used. Co-author Haruko Miura explains: “After the operation, this tissue is normally discarded. For us, it is an experimental treasure chest that enables us to tease out individual difference in the behavior of stem and other cells in the human mammary gland.”

Experimental models that are based on patient-derived tissue constitute a corner stone of basic and applied research. “This technological break-through provides the basis for many research projects, both those aimed to understand how breast cancer cells acquire aggressive traits, as well as to elucidate how adult stem cells function in normal regeneration,” says Christina Scheel, head of the study.

Background

In Germany, one in eight women is going to be diagnosed with breast cancer throughout her lifetime. In the past 30 years, the rate of newly diagnosed breast cancer cases has doubled. The reasons for this increase are unclear. Despite this greatly increased rate, mortality is declining steadily due to improved early detection and therapeutic options. Nonetheless, some aggressive subtypes of breast cancer remain poorly understood and incurable.

The aggressive behaviour of these breast cancer cells most likely originates in how the mammary gland develops and functions. The mammary gland itself consists of a structure similar in form to a bunch of grapes: a number of branching hollow ducts terminate in tiny, milk-producing pouches on one end, and the nipple on the other. This network of ducts in embedded in fatty and connective tissue which lends the breast is overall form. The mammary gland is the name-giving characteristic of mammals and provides a massive evolutionary advantage for raising offspring.

From a developmental point-of-view it is therefore essential that the highly energy-intensive process of milk production kicks in after each pregnancy. It is thought that for this purpose, the mammary gland harbours stem cells that are able to regenerate the entire mammary gland. However, how exactly such stem cells contribute to the main developmental phase of the mammary gland during puberty is not entirely clear. Without doubt, aggressive breast cancer cells activate developmental processes in an uncontrolled manner, which impacts many aspects of tumor progression. In that sense, a tumor is like an uncontrolled, regenerating organ. Importantly, elucidating how these regenerative processes are normally controlled provide the basis for the development of new targeting strategies.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health.