Climate change is likely hampering recovery efforts

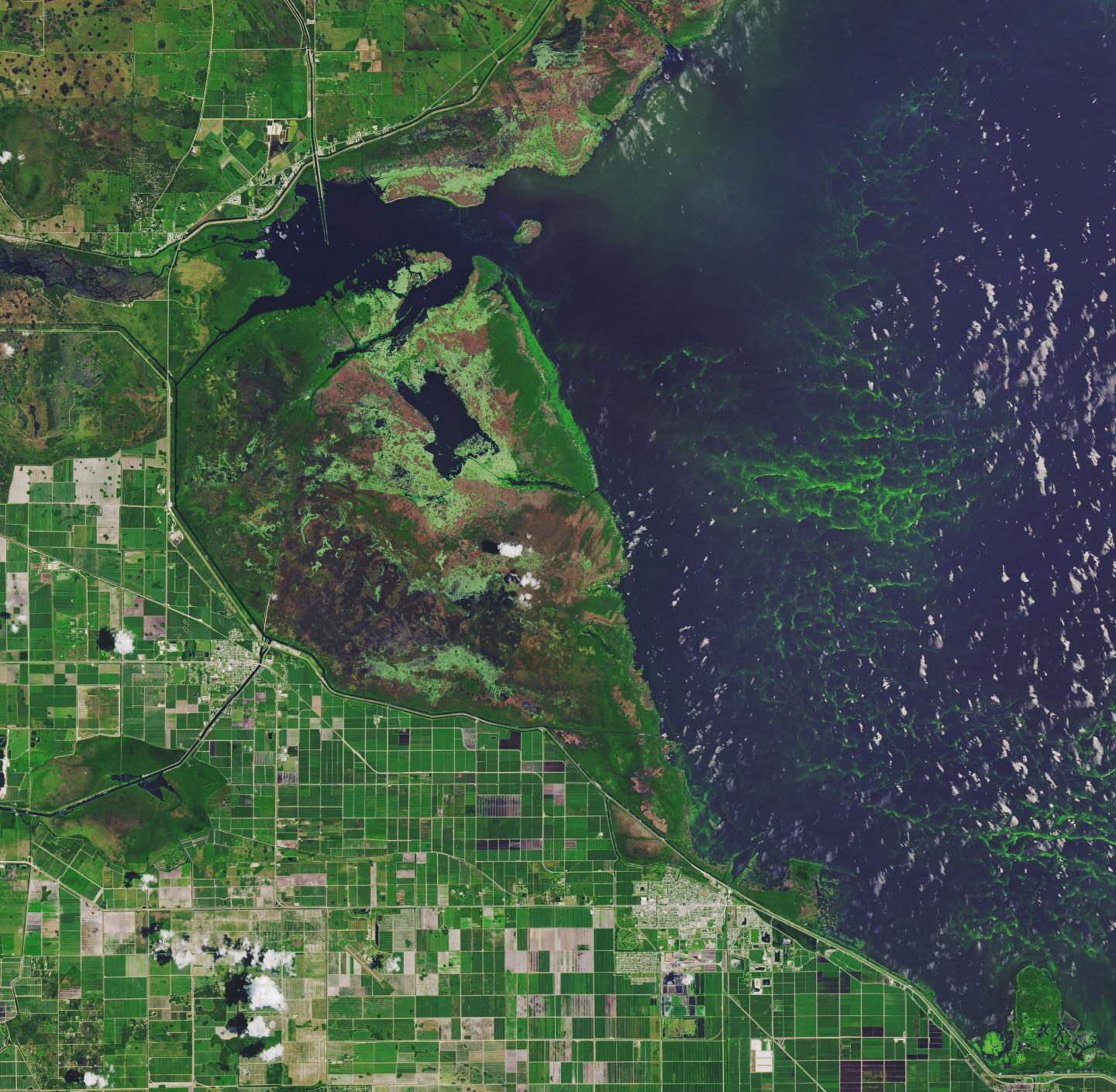

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory image made by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Washington, DC– The intensity of summer algal blooms has increased over the past three decades, according to a first-ever global survey of dozens of large, freshwater lakes, which was conducted by Carnegie’s Jeff Ho and Anna Michalak and NASA’s Nima Pahlevan and published by Nature.

Reports of harmful algal blooms–like the ones that shut down Toledo’s water supply in 2014 or led to states of emergency being declared in Florida in 2016 and 2018–are growing. These aquatic phenomena are harmful either because of the intensity of their growth, or because they include populations of toxin-producing phytoplankton. But before this research effort, it was unclear whether the problem was truly getting worse on a global scale. Likewise, the degree to which human activity –including agriculture, urban development, and climate change–was contributing to this problem was uncertain.

“Toxic algal blooms affect drinking water supplies, agriculture, fishing, recreation, and tourism,” explained lead author Ho. “Studies indicate that just in the United States, freshwater blooms result in the loss of $4 billion each year.”

Despite this, studies on freshwater algal blooms have either focused on individual lakes or specific regions, or the period examined was comparatively short. No long-term global studies of freshwater blooms had been undertaken until now.

Ho, Michalak, and Pahlevan used 30 years of data from NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey’s Landsat 5 near-Earth satellite, which monitored the planet’s surface between 1984 and 2013 at 30 meter resolution, to reveal long-term trends in summer algal blooms in 71 large lakes in 33 countries on six continents. To do so, they created a partnership with Google Earth Engine to process and analyze more than 72 billion data points.

“We found that the peak intensity of summertime algal blooms increased in more than two-thirds of lakes but decreased in a statistically significant way in only six of the lakes,” Michalak explained. “This means that algal blooms really are getting more widespread and more intense, and it’s not just that we are paying more attention to them now than we were decades ago.”

Although the trend towards more-intense blooms was clear, the reasons for this increase seemed to vary from lake to lake, with no consistent patterns among the lakes where blooms have gotten worse when considering factors such as fertilizer use, rainfall, or temperature. One clear finding, however, is that among the lakes that improved at any point over the 30-year period, only those that experienced the least warming were able to sustain improvements in bloom conditions. This suggests that climate change is likely already hampering lake recovery in some areas.

“This finding illustrates how important it is to identify the factors that make some lakes more susceptible to climate change,” Michalak said. “We need to develop water management strategies that better reflect the ways that local hydrological conditions are affected by a changing climate.”

###

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, a Google Earth Engine Research Award, a NASA ROSES grant, and by a USGS Landsat Science Team Award.

The Carnegie Institution for Science is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Media Contact

Anna Michalak

[email protected]

650-201-2667

Related Journal Article

http://dx.