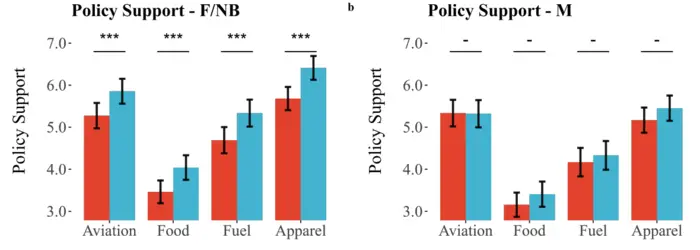

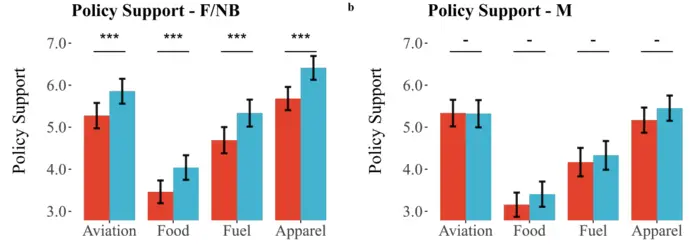

Investments in mitigating climate change in many cases benefit future generations more than those alive today. However, initial costs must be borne by those living now, so many climate mitigation policies rely on some level of intergenerational altruism for support. To investigate the strength and shape of intergenerational altruism, Gustav Agneman and colleagues asked Swedish study participants to engage in an experimental task in which they allocated fictional resources across generations, after being told how many descendants they might be expected to have in the next 250 years. On average, participants allocated most of the resources to the present generation, and fewer and fewer resources to each subsequent generation in a nearly quasi-hyperbolic curve. Participants who allocated more resources to future generations showed stronger support for contemporary climate policies. In addition, those who engaged in the intergenerational resource allocation task supported climate policies more strongly than those who did not, suggesting that thinking about potential connections to future people reduces the perceived social distance of future people and increases willingness to bear some costs in the present to benefit people in the future. Finally, although all genders allocated resources between the generations in a similar manner, the authors find that the impact of participating in the intergenerational allocation task on support for climate policies is strongly significant for women and non-binary people, but not for men. The results could have implications for creating effective climate policy communications, according to the authors.

Credit: Agneman et al

Investments in mitigating climate change in many cases benefit future generations more than those alive today. However, initial costs must be borne by those living now, so many climate mitigation policies rely on some level of intergenerational altruism for support. To investigate the strength and shape of intergenerational altruism, Gustav Agneman and colleagues asked Swedish study participants to engage in an experimental task in which they allocated fictional resources across generations, after being told how many descendants they might be expected to have in the next 250 years. On average, participants allocated most of the resources to the present generation, and fewer and fewer resources to each subsequent generation in a nearly quasi-hyperbolic curve. Participants who allocated more resources to future generations showed stronger support for contemporary climate policies. In addition, those who engaged in the intergenerational resource allocation task supported climate policies more strongly than those who did not, suggesting that thinking about potential connections to future people reduces the perceived social distance of future people and increases willingness to bear some costs in the present to benefit people in the future. Finally, although all genders allocated resources between the generations in a similar manner, the authors find that the impact of participating in the intergenerational allocation task on support for climate policies is strongly significant for women and non-binary people, but not for men. The results could have implications for creating effective climate policy communications, according to the authors.

Journal

PNAS Nexus

Article Title

Intergenerational altruism and climate policy preferences

Article Publication Date

2-Apr-2024