Credit: Robin Chemers Neustein Laboratory of Mammalian Cell Biology and Development at The Rockefeller University

Skin is our body’s most ardent defender against pathogens and other external threats. Its outermost layer is maintained through a remarkable transformation in which skin cells swiftly convert into squames–flat, dead cells that provide a tight seal between the living portion of the skin and the world outside.

“Throughout our lifetime, squames are continually being shed from the skin surface and replaced by inner cells moving outward,” says Elaine Fuchs, Rockefeller’s Rebecca C. Lancefield Professor, whose lab recently shed new light onto this process. “We’ve identified the mechanism that allows skin cells to sense new changes in their environment and very quickly deploy instructions to drive squame formation.”

Conducted in mice and described in Science, the research also provides insight into how errors in this mechanism might lead to skin conditions like atopic dermatitis and psoriasis.

Like oil and vinegar

The skin’s epidermis consists of an inner layer of stem cells that periodically stop dividing and move outward, toward the body surface. As the cells transit through subsequent layers, they face the increasingly harsh extremes of our environment, like variations in temperature. In the very last step, as they approach the surface, the cells’ nuclei and organelles are suddenly lost in the dramatic transformation into squames.

Felipe Garcia Quiroz, a former postdoctoral fellow in Fuchs’ lab, noticed something odd in the skin cells just before they turn into squames: darkly-stained protein deposits resembling the droplets you would see if you poured oil into vinegar and gave the mixture a good shake.

This phenomenon, called phase separation, occurs when liquids with mismatched properties come together: The oil prefers to be in the company of other oil, so it separates from the water-based vinegar. Phase separation is also thought to take place inside cells, where the equivalent of oil droplets are poorly understood structures that, unlike many other cellular organelles, are not bound by lipid membranes. Quiroz and his colleagues suspected that in skin cells, the dark protein deposits observed, known as keratohyalin granules, form through phase separation and carry molecular messages that, when released, prompt the cells to quickly flatten and die.

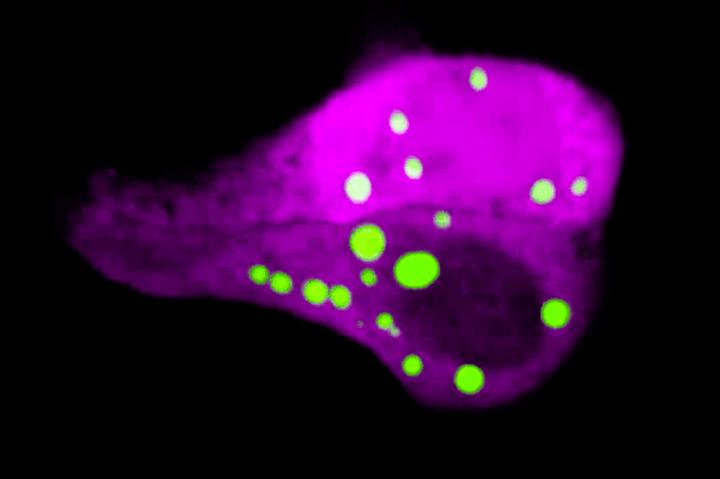

To test this idea directly in skin, Quiroz and his colleagues developed a technique to visualize phase separation dynamics without disrupting a cell’s normal processes. They created mice with a phase separation sensor, a biomolecule that emits green light under the microscope when keratohyalin granules form, and then dissipates when the granules disassemble.

With this method, the researchers were able to show that a protein called filaggrin, which is known to be mutated in some skin conditions, plays a key role in granule formation. “If filaggrin is not functioning properly, phase separation fails to occur, skin lacks keratohyalin granules, and the cells can no longer transform in response to environmental triggers,” says Quiroz.

Barrier breakdown

The findings also shed light on the underlying causes of skin conditions linked to mutations in filaggrin. For example, when Quiroz engineered filaggrin proteins mimicking mutations associated with atopic dermatitis, skin cells could no longer form normal granules. “We suspect that this lack of phase separation contributes to defects in building the skin barrier, resulting in the inflamed, cracked skin that is seen in these conditions,” he says.

Fuchs adds that the work might open up entirely new avenues for developing treatments for this and other filaggrin-linked skin diseases.

“Most treatments developed thus far have been focused on suppressing the immune system, but our findings suggest that we should be looking more closely into the barrier itself,” she says.

###

Media Contact

Katherine Fenz

[email protected]

212-327-7913

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.