Credit: Justin M. Hansen

DALLAS – May 21, 2021 – One member of a large protein family that is known to stop the spread of bacterial infections by prompting infected human cells to self-destruct appears to kill the infectious bacteria instead, a new study led by UT Southwestern scientists shows. However, some bacteria have their own mechanism to thwart this attack, nullifying the deadly protein by tagging it for destruction.

The findings, published online today in Cell, could lead to new antibiotics to fight bacterial infections. And insight into this cellular conflict could shed light on a number of other conditions in which this protein is involved, including asthma, Type 1 diabetes, primary biliary cirrhosis, and Crohn’s disease.

“This is a wonderful example of an arms race between infectious bacteria and human cells,” says study leader Neal M. Alto, Ph.D., professor of microbiology at UTSW and a member of the Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center.

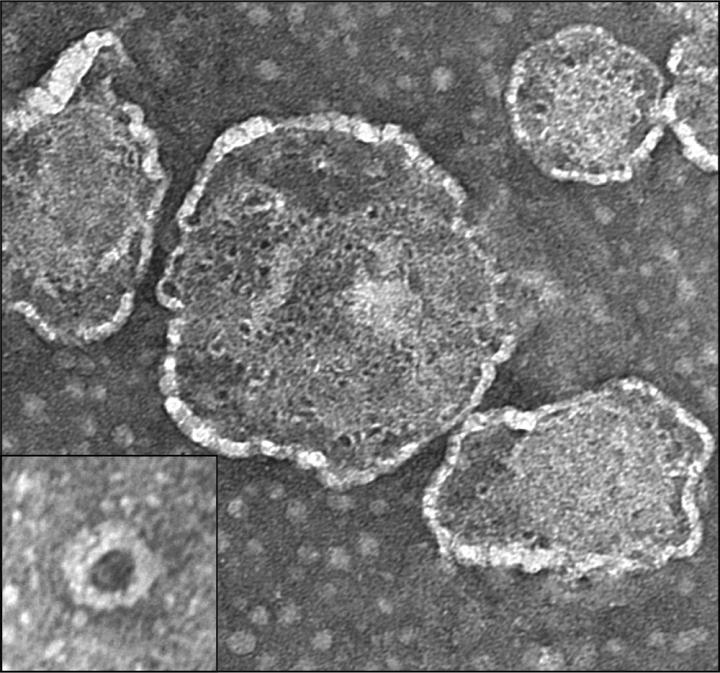

Previous research has shown that the protein, called gasdermin B (GSDMB), was different from other members of the mammalian gasdermin family. Related gasdermin proteins form pores in the membranes of infected cells, killing them while allowing inflammatory molecules to leak out and incite an immune response. However, GSDMB – found in humans but not in some other mammalian species, including rodents – doesn’t form pores in the membranes of cultured mammalian cells, leaving its target a mystery.

Using a novel screening technology, Alto and colleagues discovered that a protein toxin called IpaH7.8 from shigella flexneri, a bacterium that causes diarrheal disease, directly inhibits GSDMB. Biochemical experiments show that IpaH7.8 places a chemical tag on GSDMB that marks it for cellular destruction.

To understand why shigella flexneri rids human cells of GSDMB, the researchers placed GSDMB within synthetic mammalian and bacterial cell membranes. While GSDMB left the synthetic mammalian membranes unharmed, it poked holes in the bacterial membranes. Further investigation showed that immune cells called natural killer cells stimulate this process.

Alto notes that inhibiting the ability of shigella IpaH7.8 to counteract GSDMB could lead to new types of antibiotics. And because genetic variants of GSDMB have been linked to a variety of inflammatory diseases and cancer, better understanding this protein could lead to new treatments for these conditions too.

###

Other UTSW researchers who contributed to this study include Justin M. Hansen, Maarten F. de Jong, Qi Wu, Li-Shu Zhang, David B. Heisler, and Laura T. Alto.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI083359), The Welch Foundation (I-1704), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, (1011019) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Simons Foundation Faculty Scholars Program (55108499).

Alto holds the Lorraine Sulkin Schein Endowed Distinguished Professorship in Microbial Pathogenesis. He is the Rita C. and William P. Clements, Jr. Scholar in Medical Research and a UT Southwestern Presidential Scholar.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution’s faculty has received six Nobel Prizes, and includes 25 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 17 members of the National Academy of Medicine, and 13 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. The full-time faculty of more than 2,800 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide care in about 80 specialties to more than 117,000 hospitalized patients, more than 360,000 emergency room cases, and oversee nearly 3 million outpatient visits a year.

Media Contact

UT Southwestern Medical Center

[email protected]