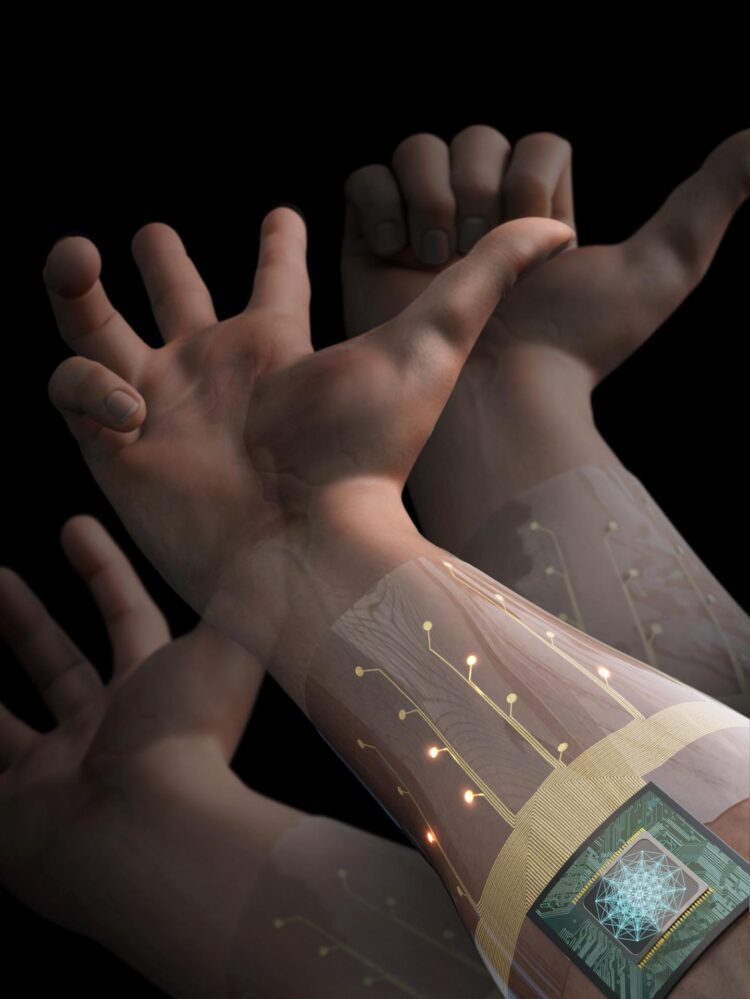

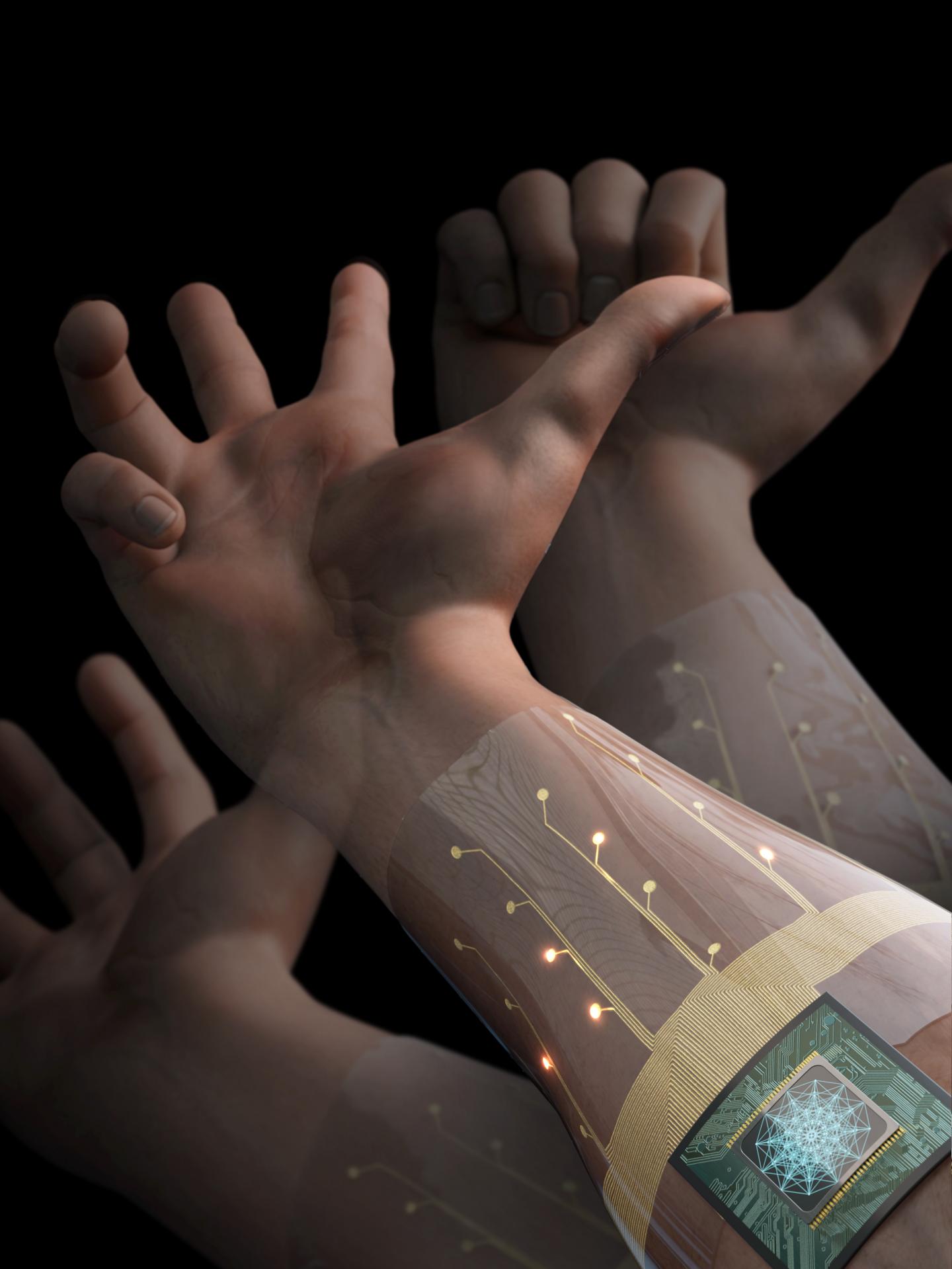

The device, which combines wearable biosensors with artificial intelligence, could be used to control prosthetics or interact with electronic devices

Credit: Image courtesy the Rabaey Lab

Berkeley — Imagine typing on a computer without a keyboard, playing a video game without a controller or driving a car without a wheel.

That’s one of the goals of a new device developed by engineers at the University of California, Berkeley, that can recognize hand gestures based on electrical signals detected in the forearm. The system, which couples wearable biosensors with artificial intelligence (AI), could one day be used to control prosthetics or to interact with almost any type of electronic device.

“Prosthetics are one important application of this technology, but besides that, it also offers a very intuitive way of communicating with computers.” said Ali Moin, who helped design the device as a doctoral student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences. “Reading hand gestures is one way of improving human-computer interaction. And, while there are other ways of doing that, by, for instance, using cameras and computer vision, this is a good solution that also maintains an individual’s privacy.”

Moin is co-first author of a new paper describing the device, which appeared online Dec. 21 in the journal Nature Electronics.

To create the hand gesture recognition system, the team collaborated with Ana Arias, a professor of electrical engineering at UC Berkeley, to design a flexible armband that can read the electrical signals at 64 different points on the forearm. The electrical signals are then fed into an electrical chip, which is programmed with an AI algorithm capable of associating these signal patterns in the forearm with specific hand gestures.

The team succeeded in teaching the algorithm to recognize 21 individual hand gestures, including a thumbs-up, a fist, a flat hand, holding up individual fingers and counting numbers.

“When you want your hand muscles to contract, your brain sends electrical signals through neurons in your neck and shoulders to muscle fibers in your arms and hands,” Moin said. “Essentially, what the electrodes in the cuff are sensing is this electrical field. It’s not that precise, in the sense that we can’t pinpoint which exact fibers were triggered, but with the high density of electrodes, it can still learn to recognize certain patterns.”

Like other AI software, the algorithm has to first “learn” how electrical signals in the arm correspond with individual hand gestures. To do this, each user has to wear the cuff while making the hand gestures one by one.

However, the new device uses a type of advanced AI called a hyperdimensional computing algorithm, which is capable of updating itself with new information.

For instance, if the electrical signals associated with a specific hand gesture change because a user’s arm gets sweaty, or they raise their arm above their head, the algorithm can incorporate this new information into its model.

“In gesture recognition, your signals are going to change over time, and that can affect the performance of your model,” Moin said. “We were able to greatly improve the classification accuracy by updating the model on the device.”

Another advantage of the new device is that all of the computing occurs locally on the chip: No personal data are transmitted to a nearby computer or device. Not only does this speed up the computing time, but it also ensures that personal biological data remain private.

“When Amazon or Apple creates their algorithms, they run a bunch of software in the cloud that creates the model, and then the model gets downloaded onto your device,” said Jan Rabaey, the Donald O. Pedersen Distinguished Professor of Electrical Engineering at UC Berkeley and senior author of the paper. “The problem is that then you’re stuck with that particular model. In our approach, we implemented a process where the learning is done on the device itself. And it is extremely quick: You only have to do it one time, and it starts doing the job. But if you do it more times, it can get better. So, it is continuously learning, which is how humans do it.”

While the device is not ready to be a commercial product yet, Rabaey said that it could likely get there with a few tweaks.

“Most of these technologies already exist elsewhere, but what’s unique about this device is that it integrates the biosensing, signal processing and interpretation, and artificial intelligence into one system that is relatively small and flexible and has a low power budget,” Rabaey said.

###

Andy Zhou is co-first author of this paper. Other authors include Abbas Rahimi, Alisha Menon, George Alexandrov, Senam Tamakloe, Jonathan Ting, Natasha Yamamoto, Yasser Khan and Fred Burghardt of UC Berkeley; Simone Benatti of the University of Bologna; and Luca Benini of ETH Zürich and the University of Bologna.

This work was supported, in part, by the CONIX Research Center, one of six centers in JUMP, a Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC) program sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The work is also based, in part, on research sponsored by the Air Force Research Laboratory under agreement number FA8650-15-2-5401, as conducted through the Flexible Hybrid Electronics Manufacturing Innovation Institute, NextFlex. Additional support was received from sponsors of the Berkeley Wireless Research Center; the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, under grant number 1106400; the ETH Zurich Postdoctoral Fellowship program and the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions for People COFUND program.

Media Contact

Kara Manke

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.