New research indicates that limited resources on Earth’s satellite could cause crowding and competition as site selection, extraction become reality

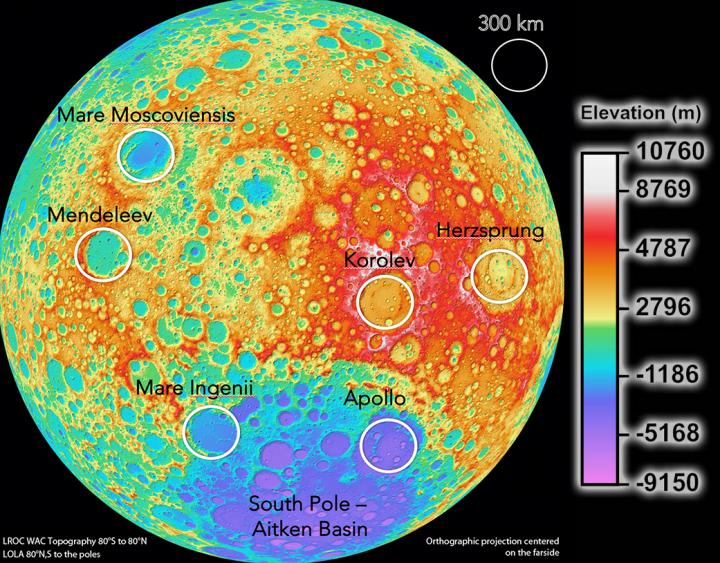

Credit: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/DLR/ASU; Overlay: M. Elvis, A. Krosilowski, T. Milligan

Cambridge, MA (November 23, 2020)–An international team of scientists led by the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, has identified a problem with the growing interest in extractable resources on the moon: there aren’t enough of them to go around. With no international policies or agreements to decide “who gets what from where,” scientists believe tensions, overcrowding, and quick exhaustion of resources to be one possible future for moon mining projects. The paper published today in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A.

“A lot of people think of space as a place of peace and harmony between nations. The problem is there’s no law to regulate who gets to use the resources, and there are a significant number of space agencies and others in the private sector that aim to land on the moon within the next five years,” said Martin Elvis, astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian and the lead author on the paper. “We looked at all the maps of the Moon we could find and found that not very many places had resources of interest, and those that did were very small. That creates a lot of room for conflict over certain resources.”

Resources like water and iron are important because they will enable future research to be conducted on, and launched from, the moon. “You don’t want to bring resources for mission support from Earth, you’d much rather get them from the Moon. Iron is important if you want to build anything on the moon; it would be absurdly expensive to transport iron to the moon,” said Elvis. “You need water to survive; you need it to grow food–you don’t bring your salad with you from Earth–and to split into oxygen to breathe and hydrogen for fuel.”

Interest in the moon as a location for extracting resources isn’t new. An extensive body of research dating back to the Apollo program has explored the availability of resources such as helium, water, and iron, with more recent research focusing on continuous access to solar power, cold traps and frozen water deposits, and even volatiles that may exist in shaded areas on the surface of the moon. Tony Milligan, a Senior Researcher with the Cosmological Visionaries project at King’s College London, and a co-author on the paper said, “Since lunar rock samples returned by the Apollo program indicated the presence of Helium-3, the moon has been one of several strategic resources which have been targeted.”

Although some treaties do exist, like the 1967 Outer Space Treaty–prohibiting national appropriation–and the 2020 Artemis Accords–reaffirming the duty to coordinate and notify–neither is meant for robust protection. Much of the discussion surrounding the moon, and including current and potential policy for governing missions to the satellite, have centered on scientific versus commercial activity, and who should be allowed to tap into the resources locked away in, and on, the moon. According to Milligan, it’s a very 20th century debate, and doesn’t tackle the actual problem. “The biggest problem is that everyone is targeting the same sites and resources: states, private companies, everyone. But they are limited sites and resources. We don’t have a second moon to move on to. This is all we have to work with.” Alanna Krolikowski, assistant professor of science and technology policy at Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T) and a co-author on the paper, added that a framework for success already exists and, paired with good old-fashioned business sense, may set policy on the right path. “While a comprehensive international legal regime to manage space resources remains a distant prospect, important conceptual foundations already exist and we can start implementing, or at least deliberating, concrete, local measures to address anticipated problems at specific sites today,” said Krolikowski. “The likely first step will be convening a community of prospective users, made up of those who will be active at a given site within the next decade or so. Their first order of business should be identifying worst-case outcomes, the most pernicious forms of crowding and interference, that they seek to avoid at each site. Loss aversion tends to motivate actors.”

There is still a risk that resource locations will turn out to be more scant than currently believed, and scientists want to go back and get a clearer picture of resource availability before anyone starts digging, drilling, or collecting. “We need to go back and map resource hot spots in better resolution. Right now, we only have a few miles at best. If the resources are all contained in a smaller area, the problem will only get worse,” said Elvis. “If we can map the smallest spaces, that will inform policymaking, allow for info-sharing and help everyone to play nice together so we can avoid conflict.”

While more research on these lunar hot spots is needed to inform policy, the framework for possible solutions to potential crowding are already in view. “Examples of analogs on Earth point to mechanisms for managing these challenges. Common-pool resources on Earth, resources over which no single actor can claim jurisdiction or ownership, offer insights to glean. Some of these are global in scale, like the high seas, while other are local like fish stocks or lakes to which several small communities share access,” said Krolikowski, adding that one of the first challenges for policymakers will be to characterize the resources at stake at each individual site. “Are these resources, say, areas of real estate at the high-value Peaks of Eternal Light, where the sun shines almost continuously, or are they units of energy to be generated from solar panels installed there? At what level can they can realistically be exploited? How should the benefits from those activities be distributed? Developing agreement on those questions is a likely precondition to the successful coordination of activities at these uniquely attractive lunar sites.”

###

Contact:

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory

Amy Oliver, Public Affairs

[email protected]

520-879-4406

Reference: “Concentrated lunar resources: imminent implications for governance and justice,” M. Elvis et al., 2020 Nov 23, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378: 20190563 [doi: http://dx.

About the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

Headquartered in Cambridge, MA, the Center for Astrophysics (CfA) | Harvard & Smithsonian is a collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.

Media Contact

Amy Oliver

[email protected]

Original Source

http://www.

Related Journal Article

http://dx.