In two mouse models, replacing the TAZ gene prevented cardiac dysfunction and scarring and reversed established cardiac dysfunction

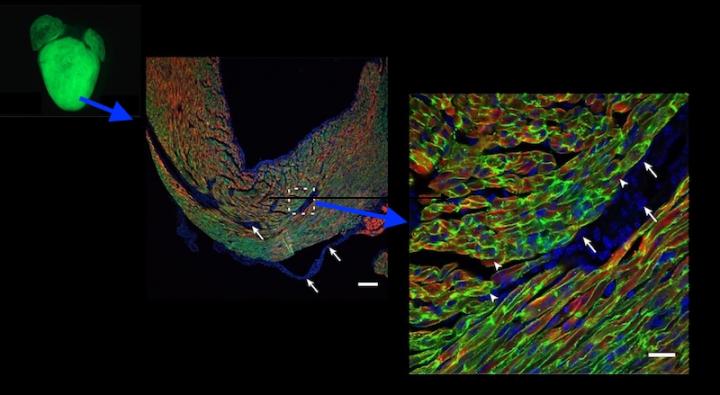

Credit: (Adapted from Prendiville TW et al., PLoS One 2015 May 29, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128105)

Barth syndrome is a rare metabolic disease in boys caused by mutation of a gene called tafazzin or TAZ. It can cause life-threatening heart failure and also weakens the skeletal muscles, undercuts the immune response, and impairs overall growth. There is no cure or specific treatment, but new research at Boston Children’s Hospital suggests that gene therapy could prevent or reverse cardiac dysfunction.

The findings, involving new mouse models of Barth syndrome, were published today “Online First” by the journal Circulation Research.

In 2014, to get a better understanding of Barth syndrome, William Pu, MD, and colleagues at Boston Children’s Hospital collaborated with the Wyss Institute to create a beating “heart on a chip” model of Barth syndrome. The model used heart-muscle cells with the TAZ mutation, derived from patients’ own skin cells. It showed that TAZ is truly at the heart of cardiac dysfunction: the heart muscle cells did not assemble normally, mitochondria inside the cells were disorganized, and heart tissue contracted weakly. Adding a healthy TAZ gene normalized these features.

But to truly capture Barth syndrome and its whole-body effects, Pu and colleagues needed an animal model. “The animal model was a hurdle in the field for a long time,” says Pu, director of Basic and Translational Cardiovascular Research at Boston Children’s and a member of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. “Efforts to make a mouse model using traditional methods had been unsuccessful.”

Modeling Barth syndrome in mice

Recently, however, the lab of Douglas Strathdee’s group at the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research in the U.K. overcame the challenge and created animal models of Barth syndrome. In new work, Pu, research fellow Suya Wang, PhD, and colleagues characterized these “knockout” mice, which came in two types. In one, the TAZ gene was deleted in cells throughout the body; in the other, just in the heart.

Most mice with the whole-body TAZ deletion died before birth, apparently because of skeletal muscle weakness. But some survived, and these mice developed progressive cardiomyopathy, in which the heart muscle enlarges and loses pumping capacity. Their hearts also showed scarring, and, similar to human patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, the heart’s left ventricle was dilated and thin-walled.

Mice lacking TAZ just in their cardiac tissue, which all survived to birth, showed the same features. Electron microscopy showed heart muscle tissue to be poorly organized, as were the mitochondria within the cells.

Pu, Wang, and colleagues then used gene therapy to replace TAZ, injecting an engineered virus under the skin (in newborn mice) or intravenously (in older mice). Treated mice with whole-body TAZ deletions were able to survive to adulthood. TAZ gene therapy also prevented cardiac dysfunction and scarring when given to newborn mice, and reversed established cardiac dysfunction in older mice — whether the mice had whole-body or heart-only TAZ deletions.

Getting the gene in

Further tests showed that TAZ gene therapy provided durable treatment of the animals’ cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle cells, but only when at least 70 percent of heart muscle cells had taken up the gene.

That’s where the challenge will lie in translating the results to humans. Simply scaling up the dose of gene therapy won’t work: In large animals like us, large doses risk a dangerous inflammatory immune response. Giving multiple doses of gene therapy won’t work either.

“The problem is that neutralizing antibodies to the virus develop after the first dose,” says Pu. “Getting enough of the muscle cells corrected in humans may be a challenge.”

Maintaining populations of gene-corrected cells is another challenge. While levels of the corrected TAZ gene remained fairly stable in the hearts of the treated mice, they gradually declined in skeletal muscles.

“The biggest takeaway was that the gene therapy was highly effective,” says Pu. “We have some things to think about to maximize the percentage of muscle cell transduction, and to make sure the gene therapy is durable, particularly in skeletal muscle.”

###

The paper’s coauthors were Yifei Lei, Qing Ma, Zhiqiang Lin, and Vassilios Bezzerides, Boston Children’s Hospital; Yang Xu and Michael Schlame, New York University School of Medicine; and Douglas Strathdee, Beatson Institute of Cancer Research. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL128694, R01 GM115593), the Barth Syndrome Foundation, the Edwin August Boger, Jr. Fund, and Boston Children’s Department of Cardiology. Pu is a member of the Medical and Scientific Advisory Board of the Barth Syndrome Foundation.

About Boston Children’s Hospital

Boston Children’s Hospital is ranked the #1 children’s hospital in the nation by U.S. News & World Report and is the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School. Home to the world’s largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center, its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, 3,000 researchers and scientific staff, including 8 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 21 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 12 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children’s research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children’s is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Discoveries blog and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens, @BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

Media Contact

Bethany Tripp

[email protected]

617-919-3110

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.