Credit: Centre for Existential Risk, Cambridge University

During the summer of 2019, a global team of experts put their heads together to define the key questions facing the UK government when it comes to biological security.

Facilitated by the Centre for Existential Risk (CSER) at the University of Cambridge and the BioRISC project at St Catharine’s College, the group of 41 academics and figures from industry and government submitted 450 questions which were then debated, voted on and ranked to define the 80 most urgent.

The final line-up includes major questions on future disease threats, including what role shifts in climate and land use might play, and whether data from social media platforms should be used to help detect the earliest signs of emerging pathogens.

Other key areas that experts believe should be a focus for investigation include questions around custom DNA synthesis and threats from “human-engineered agents”, the challenges posed by Brexit and vulnerabilities in transport and food systems, risks from “invasive alien species” in water and soil, and how best to incorporate biological security issues in scientific education.

Researchers say that these questions, published in the journal PLOS ONE, are critical to the UK’s biosecurity.

“In the year before the pandemic, the UK was ranked second in the world for global health security by the Global Health Security Index – a confidence underpinned by its 2018 Biological Security Strategy,” said Dr Luke Kemp from CSER who led the foresight research. “Clearly, improvements are needed, and not just to be ready for a future COVID-19-like crisis.”

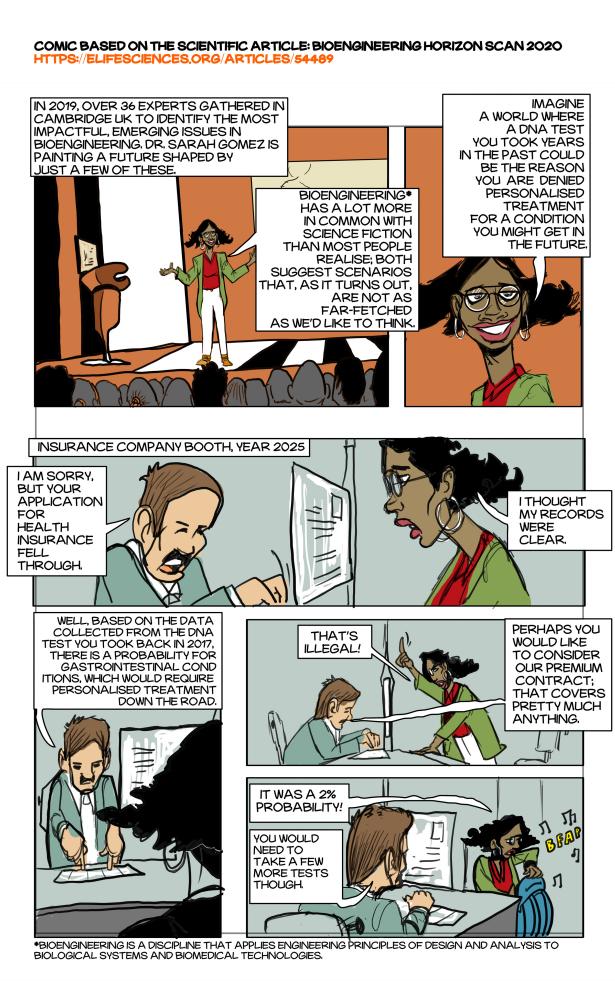

“We need to plan for a biosecure future that could see anything from brain-altering bioweapons and mass surveillance through DNA databases to low-carbon clothes produced by microorganisms. Many of these may seem to lie in the realm of science fiction but they do not. Such capabilities in bioengineering could prove even more impactful, for better or worse, than the current pandemic.”

Some of these questions are linked to an earlier ‘horizon scan’ process by many of the same experts (but part of an expanded, more global group) and also led by Kemp, which focused on the future of bioengineering.

An international team put forward issues, anonymously scored them, discussed and then voted to produce a list of twenty priority issues in the field, published in the middle of last year in the journal eLife.

The list is divided into those most immediate, and likely to come to the fore within the next five years, those on a 5-10 year timeline, and those a decade or more hence. Kemp describes this top twenty as running from the “promising to the petrifying”.

The horizon scan pointed toward the pressing concern (

“The possibility of using genetic databases for mass surveillance will only grow in coming years, particularly with the rise of new tracking and monitoring methods, powers and apps during the COVID-19 response.”

One of the highest-ranked issues for the longer-term future was the malicious uses of neurochemistry. The experts argue that advances in neuroscience and bioengineering could lead to new beneficial drugs and “nootropics”, but also new weapons.

“Imagine a world in which law enforcement uses to drugs to placate and control crowds, greatly diminishing the promise of non-violent protest movements on climate and social justice,” Kemp said.

“Regulation is critical at both the international and national level. We need to ensure that new insights into the human brain are not weaponised for either the army or police-force”.

On a more positive note, the panel of experts suggest that bioengineering will provide new ways of addressing climate change e.g. the bio-based production of materials that could lead to low-carbon plastics, clothes and construction with renewable microorganisms.

“Metabolic engineering could allow for the creation of plants and bacteria that efficiently draw-down masses of greenhouse gases. Such industrial outcomes are distant, but plausible, especially if actions such as carbon pricing are scaled up,” said Kemp.

He added: “The world, not just the UK, needs a thoughtful, transparent and evidence based way of identifying emerging issues in biosecurity and bioengineering. Whether it be a new flu pandemic, new bioweapons, or new ways to sequester carbon, forewarned is forearmed.”

###

Media Contact

Fred Lewsey

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.