Almost 100 billion nerve cells perform their service in the human brain. Each of these has an average of 1,000 contacts with other neurons. At these so-called synapses, information is passed on between the nerve cells.

Credit: © Group Schoch McGovern

Almost 100 billion nerve cells perform their service in the human brain. Each of these has an average of 1,000 contacts with other neurons. At these so-called synapses, information is passed on between the nerve cells.

However, synapses are much more than simple wiring. This can already be seen in their structure: They consist of a kind of transmitter device, the presynapse, and a receiver structure, the postsynapse. Between them lies the synaptic cleft. This is actually very narrow. Nevertheless, it prevents the electrical impulses from being easily transmitted. Instead, the neurons in a sense shout their information to each other across the gap.

For this purpose, the presynapse is triggered by incoming voltage pulses to release certain neurotransmitters. These cross the synaptic cleft and dock to specific “antennae” on the postsynaptic side. This causes them to also trigger electrical pulses in the receiver cell. “However, the amount of neurotransmitter released by the presynapse and the extent to which the postsynapse responds to it are strictly regulated in the brain,” explains Prof. Dr. Susanne Schoch McGovern of the Department of Neuropathology at University Hospital Bonn.

Sophisticated control mechanisms

For instance, certain synapses are strengthened during learning: Even a weak electrical stimulus from the transmitter neuron is then sufficient to trigger a strong response in the receiver cell. In contrast, little-used synapses atrophy. Furthermore, sophisticated control mechanisms prevent the electrical activity in the brain from spreading too far – or, conversely, from fading away too quickly. “We also speak of synaptic homeostasis,” explains Prof. Dr. Dirk Dietrich from the Department of Neurosurgery at the University Hospital. “It ensures that brain activity is always within a healthy range.”

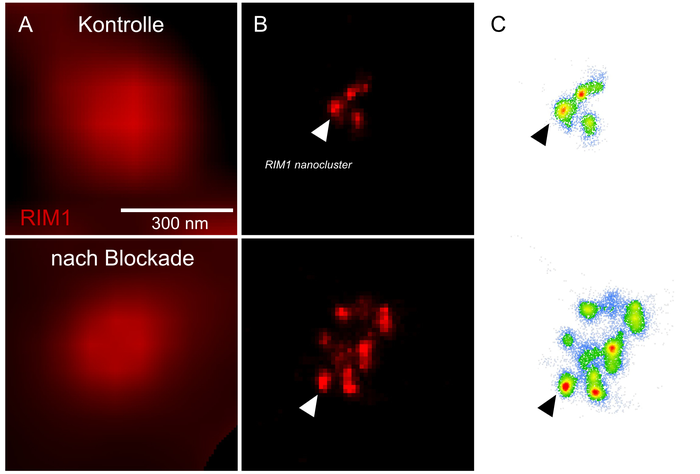

However, the processes that maintain this balance are only partially understood. One mechanism by which the brain responds to long-lasting changes in neuronal activity is known as homeostatic plasticity. “We have now shown that a protein called RIM1 plays a key role in this process,” says Schoch McGovern. RIM1 is clustered in the so-called “active zone” of the presynapse – the area where neurotransmitters are released.

Like any protein, RIM1 consists of a large number of contiguous amino acids. The researchers have now shown that some of these amino acids are linked by an enzyme to a chemical compound, a phosphate group. Depending on which amino acid is modified in this way, the presynapse can subsequently release more or less neurotransmitter. The phosphate groups form the “memory” of the synapses, so to speak, with which they remember the current activity level. “In the presynapse, transmitter-filled vesicles stand ready to be fired like the arrows of a taut bow,” Dietrich says. “As soon as a voltage pulse comes in, they are released at lightning speed. Phosphorylation changes the number of these vesicles.”

Synapse calls with louder voice

If the presynapse can “fire” more vesicles as a result, its call across the synaptic cleft becomes louder, figuratively speaking. If, on the other hand, the number of vesicles decreases sharply due to changes in the phosphorylation status of RIM1, the call is barely audible. “Which effect occurs depends on the phosphorylated amino acid,” says Dr. Johannes Alexander Müller of Schoch McGovern’s research group. He shares lead authorship of the study with his colleague Dr. Julia Betzin.

This means that the brain can presumably adjust the activity of individual synapses very precisely via RIM1. Another key role is played by the enzyme SRPK2: It attaches the phosphate groups to the amino acids of RIM1. However, there are also other players, such as enzymes that remove the phosphate groups again if necessary. “We assume that there is a whole network of enzymes that act on RIM1 and that these enzymes also control each other’s activity,” Dietrich explains.

The synaptic balance is immensely important; if it is disrupted, diseases such as epilepsy, but possibly also schizophrenia or autism can be the result. Interestingly, the genetic information for RIM1 is often altered in people with these psychiatric disorders. This may mean that the RIM1 protein is less effective in them. “We now want to further elucidate these relationships,” says Schoch McGovern, who is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area “Life and Health.” “Perhaps new therapeutic options for these diseases will emerge from our findings in the long term, although there is certainly a long way to go before that happens.”

Participating institutions and funding:

The study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the BONFOR program of the University Hospital Bonn, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), and the Cancer Research Foundation and Cancer Institute New South Wales. In addition to the University and the University Hospital Bonn, the University of Sydney and the Australian company i-Synapse were involved in the work.

Publication: Johannes Alexander Müller, Julia Betzin, Jorge Santos-Tejedor, Annika Mayer, Ana-Maria Oprişoreanu, Kasper Engholm-Keller, Isabelle Paulußen, Polina Gulakova, Terrence Daniel McGovern, Lena Johanna Gschossman, Eva Schönhense, Jesse R. Wark, Alf Lamprecht, Albert J. Becker, Ashley J. Waardenberg, Mark E. Graham, Dirk Dietrich, Susanne Schoch: A presynaptic phosphosignaling hub for lasting homeostatic plasticity; Cell Reports; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110696

Journal

Cell Reports

DOI

10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110696

Article Title

A presynaptic phosphosignaling hub for lasting homeostatic plasticity