A new group of symbiotic bacteria living with deep-sea mussels surprises with the way they fix carbon.

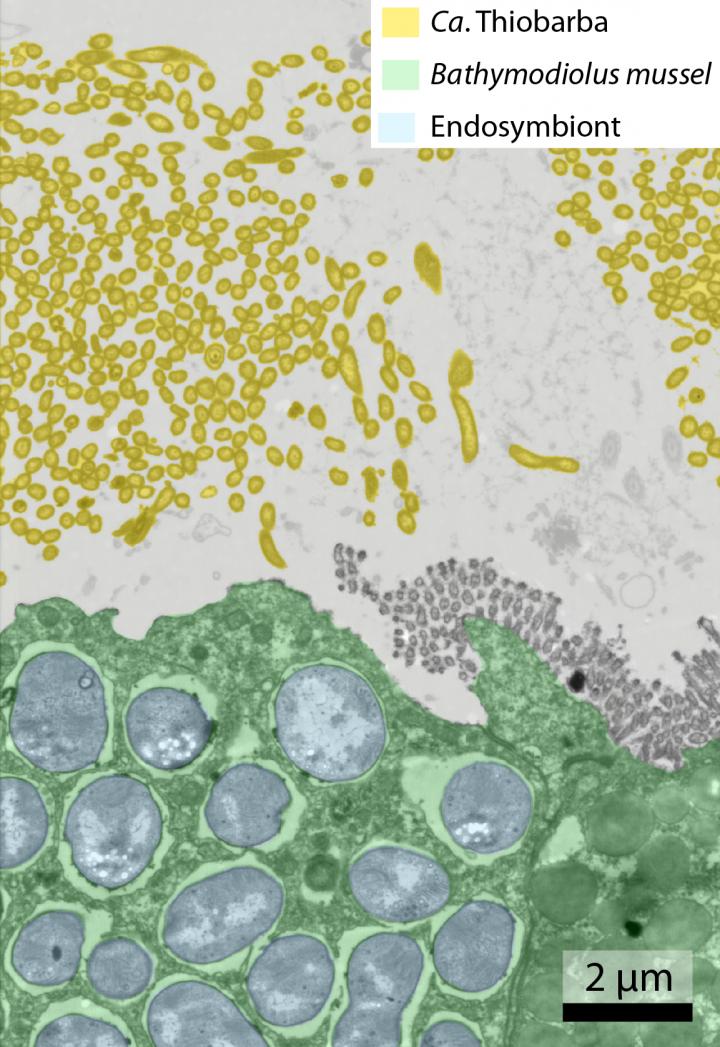

Credit: Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology / Nikolaus Leisch

In the deep sea, far away from the light of the sun, organisms use chemical energy to fix carbon. At hydrothermal vents – where hot, mineral-rich water gushes out of towering chimneys called black smokers – vibrant ecosystems are fueled by chemical energy in the vent waters. Mussels thrive in this seemingly hostile environment, nourished by symbiotic bacteria inside their gills. The bacteria convert chemicals from the vents, which the animals cannot use, into tasty food for their mussel hosts. Now an international group of scientists led by Nicole Dubilier from the Max Planck Institute of Marine Microbiology in Bremen and Jillian Petersen, now at the University of Vienna, reports in ISME Journal that carbon fixation in the deep sea is more diverse than previously thought.

Meet Thiobarba, the new bacterium on the block

It has long been known that deep-sea Bathymodiolus mussels, distant relatives of the edible, shallow-water blue mussel, harbor symbionts inside their gills. In 2016, Adrien Assié carried out his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and discovered symbiotic bacteria living between the mussel’s gills, calling them Thiobarba. Adrien’s further studies reveal that these bacteria not only belong to a family not yet known, but also feed in an unexpected way. “Thiobarba fixes carbon using the Calvin cycle,” explains Nikolaus Leisch, shared-first author of the study. “It is the first of this bacterial group to use this pathway for carbon fixation.” Usually this group uses a pathway known as the reverse TCA-cycle, which is much more energy efficient, to fix carbon. However, it does not work well in the presence of oxygen, which is abundant in the gills of these mussels. “This discovery calls into question current assumptions about which bacterial groups use which type of carbon fixation pathway,” Leisch continues.

Fixing CO2 their neighbors’ way

The Thiobarba family belongs to a group of bacteria called Epsilonproteobacteria, recently renamed as Campylobacterota. Members of this group were not known to live in symbiosis with mussels, or to use the Calvin cycle. But how did Thiobarba acquire the genetic toolbox for the Calvin cycle? “Our results, based on metagenomic sequencing, indicate that they obtained some of the required genes from other symbionts that also live inside the mussel’s gills”, says Adrien Assié, the other shared-first author of this study, who now works at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “Living within its tissue, the endosymbionts have evolved a much more intimate symbiotic relationship with the mussel. Before Thiobarba was able to successfully settle on the Bathymodiolus gills, one of its ancestors must have acquired the tools of the trade from the endosymbionts, allowing its descendants to colonize mussel hosts more efficiently.”

Symbiosis as a blueprint for evolutionary processes

The scientists next set off to look for similar processes in free-living Campylobacterota. And indeed, bacteria from water samples taken at hydrothermal vents contained the corresponding genes. Using the Calvin cycle might be more widespread in this group of bacteria than previously thought. “Our research on symbiotic bacteria has often revealed new insights that are also relevant for free-living bacteria. By studying symbioses, we can learn a lot about microbial life in general and its evolution,” project leader Nicole Dubilier concludes.

###

Media Contact

Fanni Aspetsberger

[email protected]

49-421-202-8947

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.