Research scientists led by the University of Kent have uncovered hidden diversity within a type of frog found only in the Seychelles, showing that those on each island have their own distinct lineage

Credit: Dr. Jim Labisko

Research scientists led by the University of Kent have uncovered hidden diversity within a type of frog found only in the Seychelles, showing that those on each island have their own distinct lineage.

The family tree of sooglossid frogs dates back at least 63 million years. They are living ancestors of those frogs that survived the meteor strike on earth approximately 66 million years ago, and their most recent common ancestor dates back some 63 million years, making them a highly evolutionarily distinct group.

However, recent work on their genetics led by Dr Jim Labisko from Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conversation revealed that until they can complete further investigations into their evolutionary relationships and verify the degree of differentiation between each island population, each island lineage needs to be considered as a potential new species, known as an Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU). As a result, Dr Labisko advises conservation managers they should do likewise and consider each as an ESU.

There are just four species of sooglossid frog; the Seychelles frog (Sooglossus sechellensis), Thomasset’s rock frog (So. thomasseti), Gardiner’s Seychelles frog (Sechellophryne gardineri) and the Seychelles palm frog (Se. pipilodryas).

Of the currently recognised sooglossid species, two (So. thomasseti and Se. pipilodryas) have been assessed as Critically Endangered, and two (So. sechellensis and Se. gardineri) as Endangered for the International Union for Conservation of Nature IUCN Red List. All four species are in the top 50 of ZSL’s (Zoological Society of London) Evolutionarily Distinct Globally Endangered (EDGE) amphibians.

Given the Red List and EDGE status of these unique frogs Dr Labisko and his colleagues are carrying out intensive monitoring to assess the level of risk from both climate change and disease to the endemic amphibians of the Seychelles.

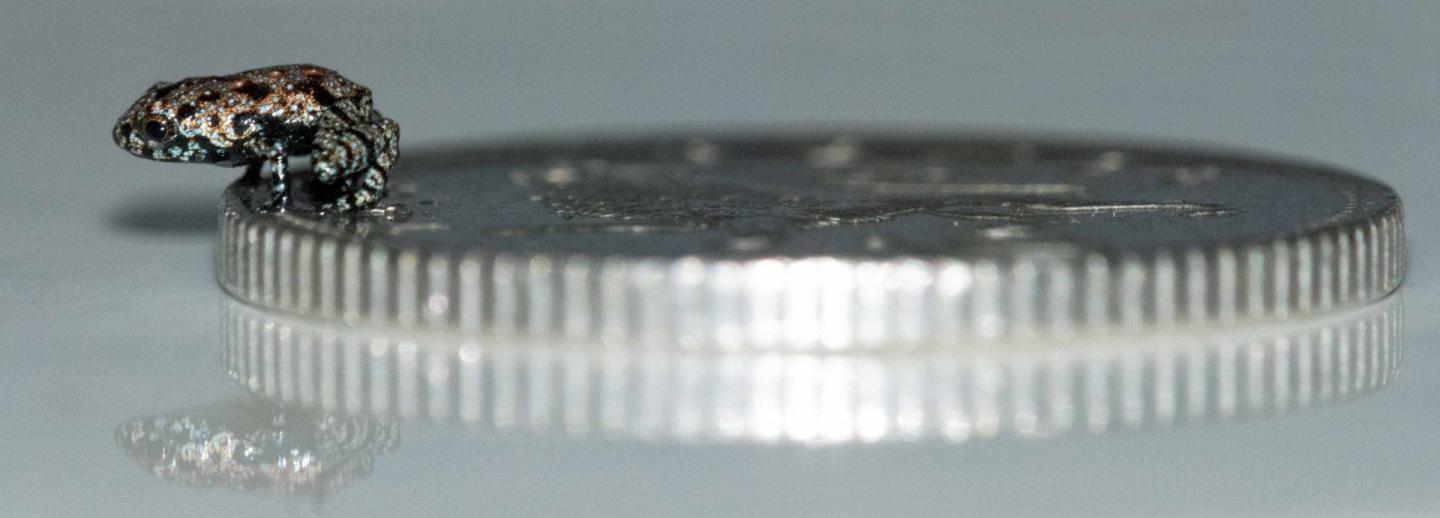

Dr Labisko, who completed his PhD on sooglossid frogs at Kent’s Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology in 2016 said many of these frogs are so small and good at hiding the only way to observe them is by listening for their calls. Although tiny, the sound they emit can be around 100 decibels, equivalent to the sound volume of a power lawnmower’.

Dr Labisko’s team are using sound monitors to record the vocal activity of sooglossid frogs for five minutes every hour, every day of the year, in combination with dataloggers that are sampling temperature and moisture conditions on an hourly basis

Dr Labisko said: ‘Amphibians play a vital role in the ecosystem as predators, munching on invertebrates like mites and mosquitos, so they contribute to keeping diseases like malaria and dengue in check. Losing them will have serious implications for human health.’

As a result of this study into the frogs, the research team will also contribute to regional investigations into climate change, making a local impact in the Seychelles.

Amphibians around the world are threatened by a lethal fungus known as chytrid. The monitoring of these sooglossid frogs will provide crucial data on amphibian behaviour in relation to climate and disease. If frogs are suddenly not heard in an area where they were previously, this could indicate a range-shift in response to warming temperatures, or the arrival of disease such as chytrid – the Seychelles is one of only two global regions of amphibian diversity where the disease is yet to be detected.

It may also impact on a variety of other endemic Seychelles flora and fauna, including the caecilians, a legless burrowing amphibian that is even more difficult to study than the elusive sooglossids.

Researchers know that caecilians can be found in similar habitats to the frogs, so they can use the frog activity and environmental data they are collecting to infer caecilian presence or absence and generate appropriate conservation strategies as a result.

Endemic, endangered and evolutionarily significant: cryptic lineages in Seychelles’ frogs (Anura: Sooglossidae) by Jim Labisko Richard A Griffiths Lindsay Chong-Seng Nancy Bunbury Simon T Maddock Kay S Bradfield Michelle L Taylor Jim J Groombridge is published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

###

https:/

https:/

https:/

For further information and interview or image requests contact Sandy Fleming at the University of Kent Press Office.

Tel: +44 (0)1227 823581

Email: [email protected]

News releases can also be found at http://www.

University of Kent on Twitter: http://twitter.

Notes to editors

The project is supported by the Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund and working with partners including Island Conservation Society, Seychelles Islands Foundation, and Seychelles National Parks Authority.

It and the work on the evolutionary relationships of sooglossid frogs also forms part of Dr Labisko’s teaching in Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conversation to both BSc and PG students.

Global caecilian experts from the Natural History Museum, London, and the University of Wolverhampton, as well as local expertise from Seychelles Natural History Museum and the Island Biodiversity and Conservation centre of the University of Seychelles are also involved in the project, and helping to design strategies to monitor both frogs and caecilians in Seychelles.

The work of Dr Labisko is part of a suite of research and conservation activities by the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology on Seychelles endemics that includes work on the Seychelles paradise flycatcher, and Seychelles black parrot, and stems from the Darwin Initiative Project ‘A cutting-EDGE approach to saving Seychelles’ evolutionarily distinct biodiversity’ that ran from 2012-2015, headed by Professor Jim Groombridge.

https:/

Established in 1965, the University of Kent – the UK’s European university – now has almost 20,000 students across campuses or study centres at Canterbury, Medway, Tonbridge, Brussels, Paris, Athens and Rome.

It was ranked 22nd in the Guardian University Guide 2018 and in June 2017 was awarded a gold rating, the highest, in the UK Government’s Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF).

In 2018 it was also ranked in the top 500 of Shanghai Ranking’s Academic Ranking of World Universities and 47th in the Times Higher Education’s (THE) new European Teaching Rankings.

Kent is ranked 17th in the UK for research intensity (REF 2014). It has world-leading research in all subjects and 97% of its research is deemed by the REF to be of international quality.

Along with the universities of East Anglia and Essex, Kent is a member of the Eastern Arc Research Consortium (http://www.

The University is worth £0.7 billion to the economy of the south east and supports more than 7,800 jobs in the region. Student off-campus spend contributes £293.3m and 2,532 full-time-equivalent jobs to those totals.

Kent has received two Queen’s Anniversary prizes for Higher and Further Education.

Media Contact

Sandy Fleming

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.