Combination of research methods reveals causes of capacity fading, giving scientists better insight to design advanced batteries for electric vehicles

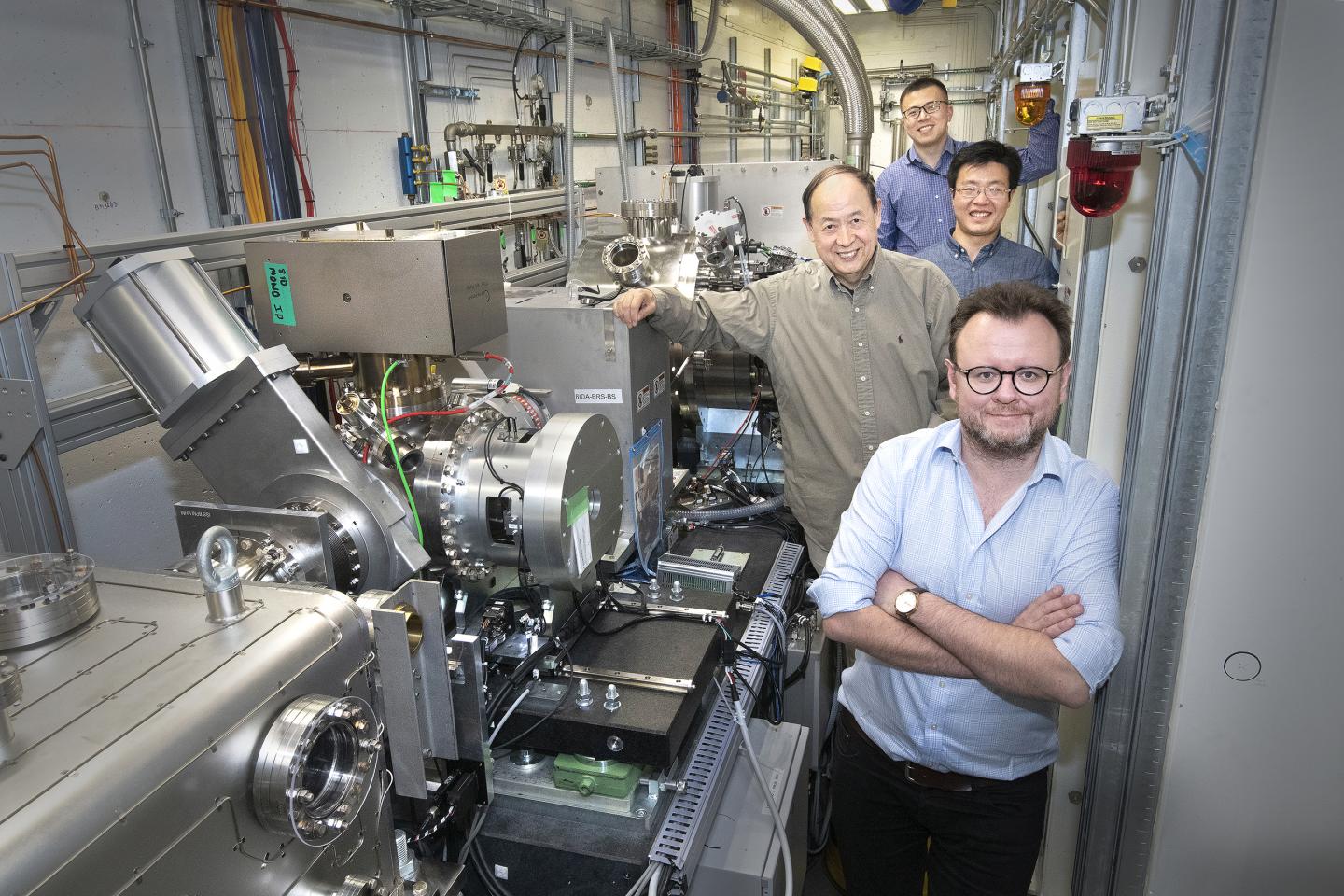

Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

A team of scientists including researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have identified the causes of degradation in a cathode material for lithium-ion batteries, as well as possible remedies. Their findings, published on Mar. 7 in Advanced Functional Materials, could lead to the development of more affordable and better performing batteries for electric vehicles.

Searching for high-performance cathode materials

For electric vehicles to deliver the same reliability as gas vehicles they need lightweight yet powerful batteries. Lithium-ion batteries are the most common type of battery found in electric vehicles today, but their high cost and limited lifetimes are limitations to the widespread deployment of electric vehicles. To overcome these challenges, scientists at many of DOE’s national labs are researching ways to improve the traditional lithium-ion battery.

Batteries are composed of an anode, a cathode, and an electrolyte, but many scientists consider the cathode to be the most pressing challenge. Researchers at Brookhaven are part of a DOE-sponsored consortium called Battery500, a group that is working to triple the energy density of the batteries that power today’s electric vehicles. One of their goals is to optimize a class of cathode materials called nickel-rich layered materials.

“Layered materials are very attractive because they are relatively easy to synthesize, but also because they have high capacity and energy density,” said Brookhaven chemist Enyuan Hu, an author of the paper.

Lithium cobalt oxide is a layered material that has been used as the cathode for lithium-ion batteries for many years. Despite its successful application in small energy storage systems such as portable electronics, cobalt’s cost and toxicity are barriers for the material’s use in larger systems. Now, researchers are investigating how to replace cobalt with safer and more affordable elements without compromising the material’s performance.

“We chose a nickel-rich layered material because nickel is less expensive and toxic than cobalt,” Hu said. “However, the problem is that nickel-rich layered materials start to degrade after multiple charge-discharge cycles in a battery. Our goal is to pinpoint the cause of this degradation and provide possible solutions.”

Determining the cause of capacity fading

Cathode materials can degrade in several ways. For nickel-rich materials, the problem is mainly capacity fading–a reduction in the battery’s charge-discharge capacity after use. To fully understand this process in their nickel-rich layered materials, the scientists needed to use multiple research techniques to assess the material from different angles.

“This is a very complex material. Its properties can change at different length scales during cycling,” Hu said. “We needed to understand how the material’s structure changed during the charge-discharge process both physically–on the atomic scale up–and chemically, which involved multiple elements: nickel, cobalt, manganese, oxygen, and lithium.”

To do so, Hu and his colleagues characterized the material at multiple research facilities, including two synchrotron light sources–the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) at Brookhaven and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at SLAC. Both are DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

“At every length scale in this material, from angstroms to nanometers and to micrometers, something is happening during the battery’s charge-discharge process,” said co-author Eli Stavitski, beamline scientist at NSLS-II’s Inner Shell Spectroscopy (ISS) beamline. “We used a technique called x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) here at ISS to reveal an atomic picture of the environment around the active metal ions in the material.”

Results from the XAS experiments at NSLS-II led the researchers to conclude that the material had a robust structure that did not release oxygen from the bulk, challenging previous beliefs. Instead, the researchers identified that the strain and local disorder was mostly associated with nickel.

To investigate further, the team conducted transmission x-ray microscopy (TXM) experiments at SSRL, mapping out all the chemical distributions in the material. This technique produces a very large set of data, so the scientists at SSRL applied machine learning to sort through the data.

“These experiments produced a huge amount of data, which is where our computing contribution came in,” said co-author Yijin Liu, a SLAC staff scientist. “It wouldn’t have been practical for humans to analyze all of this data, so we developed a machine learning approach that searched through the data and made judgments on which locations were problematic. This told us where to look and guided our analysis.”

Hu said, “The major conclusion we drew from this experiment was that there were considerable inhomogeneities in the oxidation states of the nickel atoms throughout the particle. Some nickel within the particle maintained an oxidized state, and likely deactivated, while the nickel on the surface was irreversibly reduced, decreasing its efficiency.”

Additional experiments revealed small cracks formed within the material’s structure.

“During a battery’s charge-discharge process, the cathode material expands and shrinks, creating stress,” Hu said. “If that stress can be released quickly then it does not cause a problem but, if it cannot be efficiently released, then cracks can occur.”

The scientists believed that they could possibly mitigate this problem by synthesizing a new material with a hollowed structure. They tested and confirmed that theory experimentally, as well as through calculations. Moving forward, the team plans to continue developing and characterizing new materials to enhance their efficiency.

“We work in a development cycle,” Stavitski said. “You develop the material, then you characterize it to gain insight on its performance. Then you go back to a synthetic chemist to develop an advanced material structure, and then you characterize that again. It’s a pathway to continuous improvement.”

Additionally, as NSLS-II continues to build up its capabilities, the scientists plan to complete more advanced TXM experiments on these kinds of materials, taking advantage of NSLS-II’s ultrabright light.

###

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation and DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Operations at NSLS-II and SSRL are supported by DOE’s Office of Science.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

Media Contact

Stephanie Kossman

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.