The finding could improve recovery from abdominal and pelvic surgery

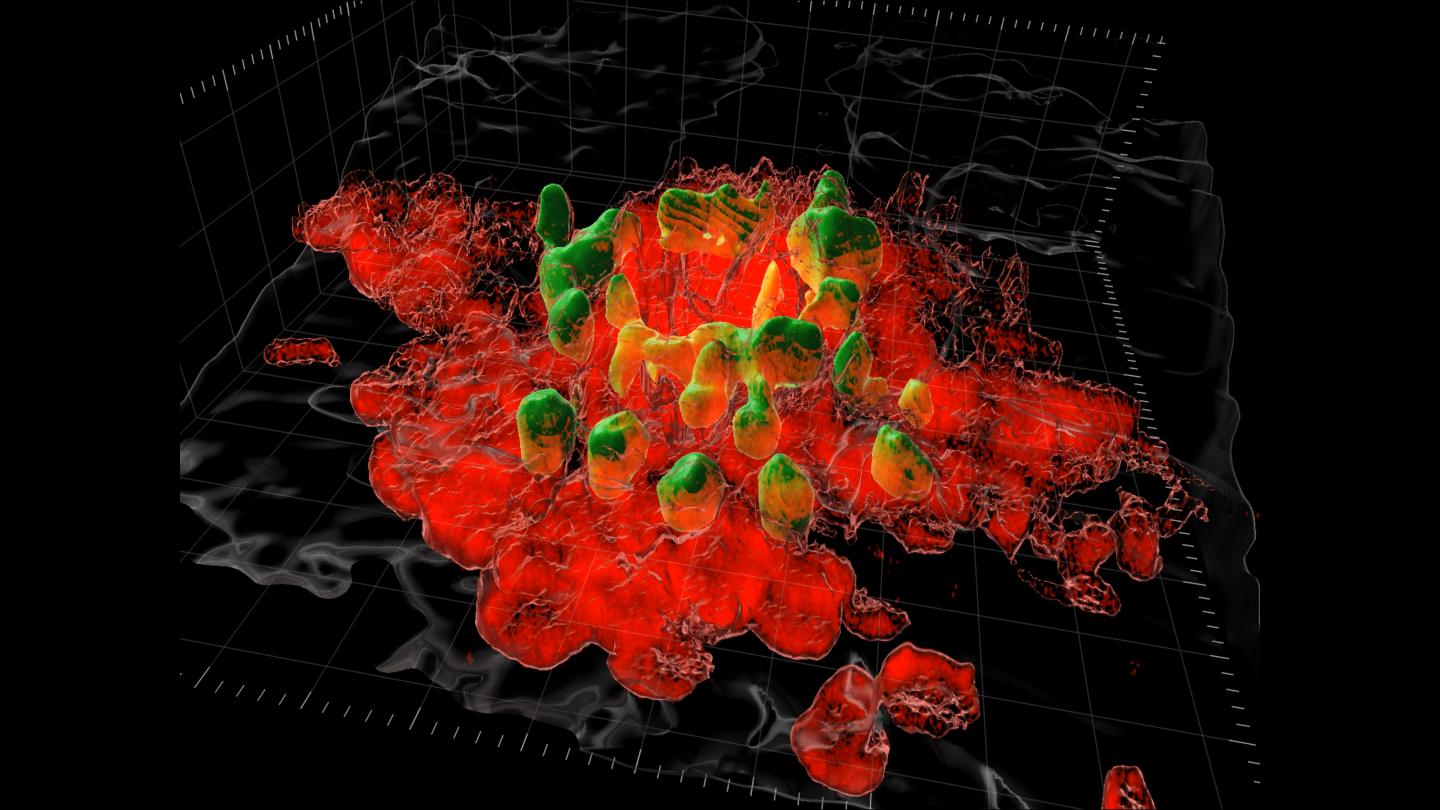

Credit: Supplied by Kubes’ Lab, Snyder Institute for Chronic Disease, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what’s causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

“This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women,” says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University of Bern, Switzerland, and first author on the study who worked on this research as a Swiss National Science Foundation research fellow at the University of Calgary. “People sometimes require a second surgery.”

The research published in Science, was conducted in mice and shows the excess scarring is caused by macrophages, a type of white blood cell that rushes to the surgical site to start to repair the injury.

“Joel developed a new method using the highly specialized imaging equipment in my lab that gave scientists the first look at what these macrophages are doing in real-time,” says Dr. Paul Kubes, PhD, principal investigator on the study and professor at the Cumming School of Medicine. “We are still working to understand why the macrophages take on this repair work as they are known for attacking pathogens. Whatever they are responding to, it’s clear their involvement is causing the scarring problem.”

The researchers also discovered two ways to inhibit this natural response. They either removed the macrophages, or they introduced a drug to block the macrophage stickiness. Both processes were very effective in stopping the adhesions.

“We believe the macrophage response has not made the evolutionary leap to understand that surgery is beneficial and not a threat to survival,” says Kubes. “It’s possible, that the body is reacting to the surgery, that having the organs exposed to the environment is interpreted as a threat, like an attack from a predator. The body doesn’t understand that the surgeon will do the critical repair work.”

Macrophages are also present in humans, and the research team believes the response seen in mice is likely to translate to both adults and children. They hope to move to trials on human cells, soon, and eventually clinical trials.

“Every surgeon does operations for people who have these abdominal adhesions,” says Zindel. “It would be amazing to be able to prevent this surgical complication. It would not only benefit individuals, it would create significant savings for the healthcare system, by reducing hospital costs for readmission and surgery.”

###

The basic research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council while the clinical application was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Kubes is supported by Heart & Stroke and the CIHR Canada Research Chairs Program and Zindel is supported from a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

This research was possible with support from the Nicole Perkins Microbial Communities Core Lab, the Live Cell Imaging Resource Laboratory at the Cumming School of Medicine, and the Microscopy Imaging Center (MIC) of the University of Bern.

Media Contact

Kelly Johnston

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.