UC biologists create a novel device to determine how well animals discern color

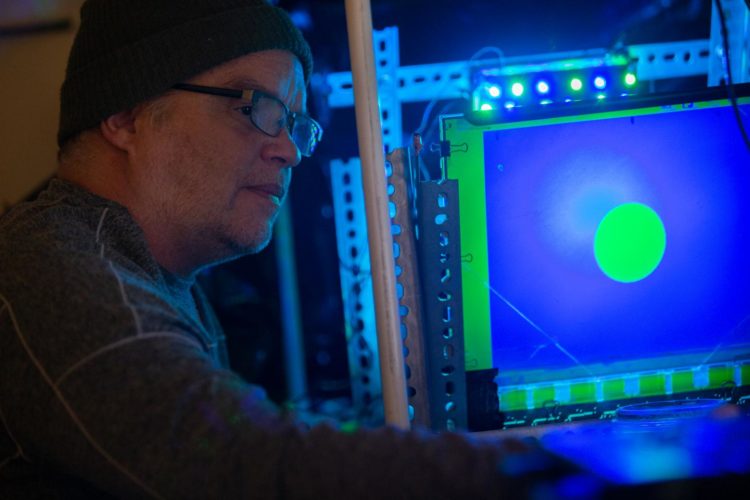

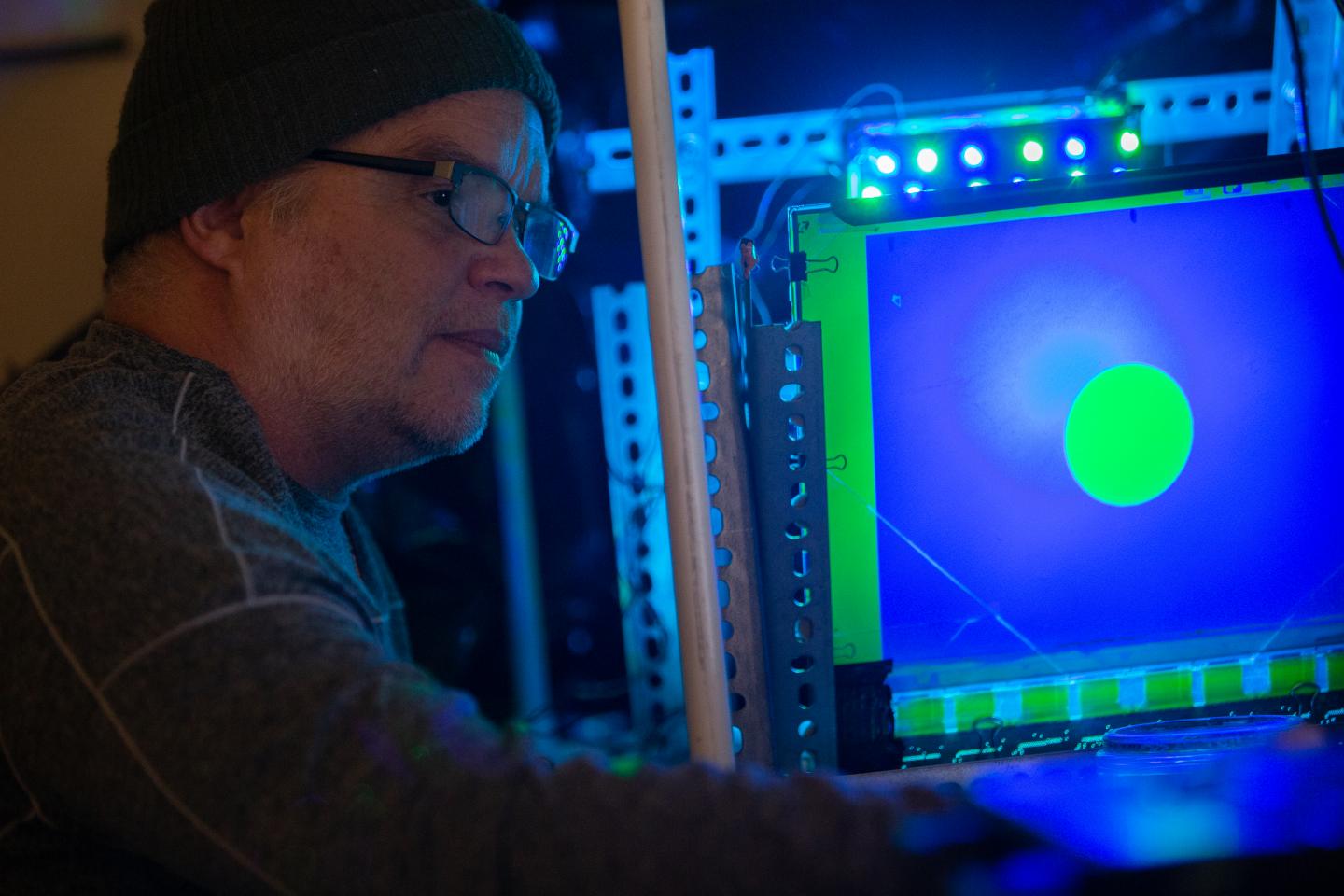

Credit: Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

Fiddler crabs have a simple solution to life’s daily perils: run.

University of Cincinnati biologists are using this compulsion to test the crabs’ color vision using simple modified electronics.

Most people can detect a huge variety of colors – more than 1 million. We can even tell when one shade is slightly different from another. UC biologist John Layne wants to know if crabs can do likewise.

Layne and his students created a miniature movie theater that uses a stripped-down liquid crystal display like the kind found in many computer monitors. A crab is placed in a little glass arena under a tilted screen projecting a video illuminated in color by blue and green light-emitting diodes.

?The video shows a looming stimulus — a round ball that appears to approach the crabs quickly on screen — like the famous boulder scene in “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

And like Indiana Jones, the crabs react in kind.

“They run like a bat out of hell. Their reaction is not subtle. They will sprint really fast and bang into the wall,” Layne said.

The consistent reaction to the approaching virtual ball helps UC biologists measure the spectrum of visible light the crabs can see.

“We’re using it to test color discrimination. For an animal to have color vision, what that really means is the ability to discriminate different wavelengths of light,” Layne said. “They can see green light. They can see blue light. But can they tell the difference? That’s the test.”

Layne and student co-authors Jeremiah Didion and Karleigh Smith described their vision-testing device in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution.

Researchers have only begun to explore the complex visual abilities of animals. While we can see about 1 million colors, some spiders are believed to see 100 times that. And the reigning record holder? Scientists believe it’s the mantis shrimp, which has four times as many color receptors as we do.

“Just having these color cells doesn’t mean they use them for color vision like we do. They might just have these cells that cover more of the spectrum to capture more light,” Layne said. “That would be advantageous for animals that live in dim or dark conditions.”

Fiddler crabs usually have the opposite problem: too much light, Layne said. Their eyes sit on tall eyestalks that serve as periscopes to peer across the mudflats. Their eyes wrap around the tips of these eyestalks.

“Part of their eye is staring at the sun at all times. That is a problem for them,” Layne said.

They compensate with screening pigments that prevent their vision cells from getting fried by excessive solar radiation, he said.

Layne keeps his fiddler crabs in ingenious tanks that mimic the changing tides, draining from one tank to the other and back in slightly more than six-hour intervals. At “low tide,” the tank’s algae-covered rocks are exposed for the crabs. A second tank is full of deep sand so the crabs can dig burrows that periodically flood with rising tide.

The male crabs skitter sideways, holding their larger “fiddle” claw in front of them like a gladiator’s shield. Some are right-clawed; some left-clawed. It’s random. Females have two equally small front claws.

Didion is continuing his biology studies at Case Western Reserve University. He said insights we gain from animals can lead in surprising directions.

“The value of studying the animal kingdom is exploration. You feel like a modern-day explorer,” Didion said. “You never know where the next big contribution to science will come from.”

###

Media Contact

Michael Miller

[email protected]

513-556-6757

Related Journal Article

http://dx.