Segmented filamentous bacteria, a specific bacterium within the healthy gut microbiome, significantly influences the immune system to impair bone mass accrual during post-pubertal skeletal development

Credit: Dr. Chad M. Novince from the Medical University of South Carolina

Microbes are often seen as pathogens that cause disease, but the picture is actually more complex than that limited view. The gut microbiome, which is the collection of microorganisms that colonize the healthy gut, is considered a supporting organ that can regulate host biological functions, including skeletal health. Researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) who study osteoimmunology, the interface of the skeletal and immune systems, have examined the impact of a specific microorganism, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), on post-pubertal skeletal development. Their results, published online on Jan. 10 in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research Plus, showed that SFB elevated the response of specific immune cells in the gut and liver. This response led to increased osteoclast activity and decreased osteoblast activity, cumulatively impairing bone mass accrual.

“This is the first known report to show that within the complex gut microbiome, specific microbes have the capacity to effect normal skeletal growth and maturation,” said Chad M. Novince, D.D.S., Ph.D., an assistant professor in the colleges of Medicine and Dental Medicine, who studies the impact of the microbiome on osteoimmunology and skeletal development.

The Novince lab focuses on the post-pubertal phase of skeletal development, the critical window of plasticity that supports the accrual of approximately 40% of a person’s peak bone mass. Recent work from the lab showed that the gut microbiome heightens immune responses in the liver and bone environment, which impairs skeletal bone mass. SFB has been shown by other groups to activate the immune response of TH17 cells in an interleukin-17A (IL-17A) dependent manner. The research aimed to link these aspects of SFB-mediated immunity determine if specific gut microbes have the ability to affect skeletal health.

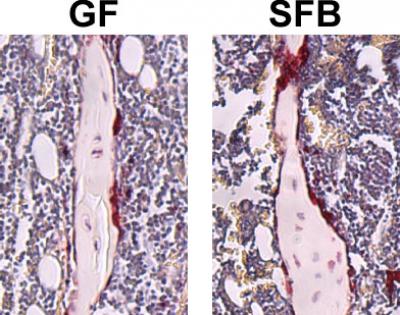

To study the effects of SFB and the gut microbiome on skeletal health, the Novince lab utilized a mouse model with a defined microbiota. This research was facilitated by MUSC’s Gnotobiotic Animal Core, which is directed by Caroline Westwater, Ph.D., co-author and professor in the College of Dental Medicine. Available through the unique animal core, germ-free mice (no microbiota) and gnotobiotic mice (defined microbiota) provide an excellent model for studying the contributions of the microbiome to skeletal development.

“Whenever we think of bone, it’s always the balance of osteoblasts and osteoclasts; the osteoblasts form the bone, and the osteoclasts resorb the bone,” said Novince. “SFB colonization caused a shift in both sides of the axis: the osteoclast activity went up, and the osteoblast activity went down, which is detrimental to the skeleton.”

To begin its studies, the Novince lab compared germ-free mice to SFB-monoassociated mice. Mice that had SFB exhibited a 20% reduction in trabecular bone volume – the type of bone that undergoes high rates of bone metabolism. Further examination of these mice showed that SFB colonization led to increased IL-17A levels in the gut and circulation, and enhanced osteoclast potential.

Next, the Novince lab examined whether the presence of SFB within a complex gut microbiota could influence normal skeletal development. They compared Taconic specific-pathogen-free mice that had SFB as part of their microbiome to Taconic specific-pathogen-free mice that lacked SFB.

The presence of SFB within a complex microbiota led to reduced trabecular bone volume, which was attributed to increased osteoclast activity and decreased osteoblast activity. SFB colonization led to a proinflammatory immune state in the gut, with increased numbers of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and M1-macrophages in the lymph nodes associated with the gut. Moreover, SFB colonization increased IL-17A levels in the gut and circulation.

Interestingly, the SFB presence in a complex gut microbiota also profoundly stimulated hepatic immunity. SFB colonization upregulated proinflammatory immune factors in the liver and increased TH17 cells in the liver draining lymph nodes. Furthermore, the presence of SFB led to higher levels of acute phase reactants – immune factors that are made in the liver and secreted into the circulation. Lipocalin-2 (LCN2) was particularly interesting because it is an antimicrobial peptide that influences bone metabolism.

SFB colonization resulted in increased circulating levels of IL-17A and LCN2, which are both factors that support osteoclast activity and suppress osteoblast activity. Taken together, these data show that SFB plays a critical role in regulating the immune response in both the gut and liver which has significant effects on the skeleton and provides strong support that gut microbiota actions on the skeleton are mediated in part through a Gut-Liver-Bone Axis.

Additionally, the contribution of SFB to skeletal health may have significant clinical implications.

“If we can prevent the colonization or deplete specific microbes such as SFB from the microbiome, there is a clinical potential to optimize bone mass accrual during post-pubertal skeletal development,” said Novince.

It is known that diet, probiotics and antibiotics have significant effects on the make-up of the microbiome, including SFB colonization. A majority of a person’s bone mass accrues during adolescence, or postpubescently. As people age, they slowly begin to lose bone mass, which puts them at risk for fractures and osteoporosis. Modulation of SFB, through non-invasive interventions such as diets or probiotics, could allow for the build-up or optimization of peak bone mass accrual during adolescence. This would limit the risk for aging associated low bone mass and related fractures.

In summary, Novince’s group has shown that within the complex microbiome, a specific commensal microbe, SFB, has the capacity to critically change the way the microbiome interacts with the host immune system and skeleton. This immune response, mediated through a Gut-Liver-Bone Axis, induces a pro-osteoclast and anti-osteoblast environment in the bone, which impairs normal skeletal growth and maturation. The strong contribution of hepatic immunity warrants further investigation into how the acute phase products may have a feedback effect on the microbiome or additional effects on the host.

###

About MUSC

Founded in 1824 in Charleston, MUSC is the oldest medical school in the South, as well as the state’s only integrated, academic health sciences center with a unique charge to serve the state through education, research and patient care. Each year, MUSC educates and trains more than 3,000 students and 700 residents in six colleges: Dental Medicine, Graduate Studies, Health Professions, Medicine, Nursing and Pharmacy. The state’s leader in obtaining biomedical research funds, in fiscal year 2018, MUSC set a new high, bringing in more than $276.5 million. For information on academic programs, visit http://musc.

As the clinical health system of the Medical University of South Carolina, MUSC Health is dedicated to delivering the highest quality patient care available while training generations of competent, compassionate health care providers to serve the people of South Carolina and beyond. Comprising some 1,600 beds, more than 100 outreach sites, the MUSC College of Medicine, the physicians’ practice plan and nearly 275 telehealth locations, MUSC Health owns and operates eight hospitals situated in Charleston, Chester, Florence, Lancaster and Marion counties. In 2019, for the fifth consecutive year, U.S. News & World Report named MUSC Health the No. 1 hospital in South Carolina. To learn more about clinical patient services, visit http://muschealth.

Media Contact

Heather Woolwine

[email protected]

843-792-7669

Related Journal Article

http://dx.