Credit: Copyright: NIOZ

For the first time, researchers from the SponGES project collected year-round video footage and hydrodynamic data from the mysterious world of a deep-sea sponge ground in the Arctic. Deep-sea sponge grounds are often compared to the rich ecosystems of coral reefs and form true oases. In a world where all light has disappeared and without obvious food sources, they provide a habitat for other invertebrates and a refuge for fish in the otherwise barren landscape. It is still puzzling how these biodiversity hotspots survive in this extreme environment as deep as 1500 metres below the water surface. With over 700 hundred hours of footage and data on food supply, temperature, oxygen concentration, and currents, NIOZ scientists Ulrike Hanz and Furu Mienis found clues that could help find some answers.

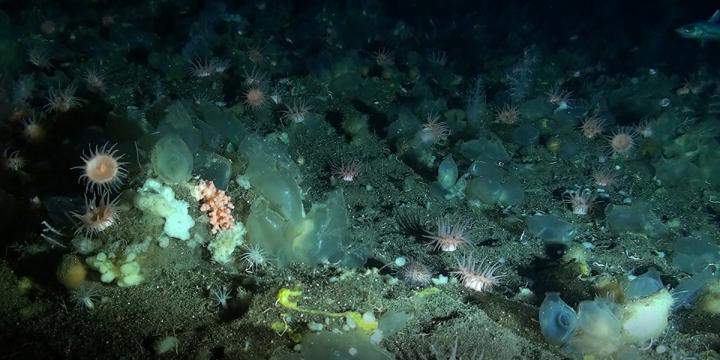

Colourful, thriving communities

‘The deep sea, in most places, is barren and flat’, says marine geologist Furu Mienis. ‘And then, suddenly, we have these sponge grounds that form colourful, thriving communities. It is intriguing how this system sustains itself in such a place.’ To better understand this unexpected success, the research team deployed a bottom lander equipped with sensors and an underwater camera specially designed for the extreme environment by NIOZ engineers and technicians. The location: an enormous seamount in the Norwegian Sea that is part of the Mid Atlantic ridge, known as the Schulz Bank. A year later they picked it up. What they saw and measured was a world where sponges survived in temperatures below zero degrees Celsius and withstood potential food deprivation, high current speeds and 200-metre-high underwater waves.

Mienis: ‘We still don’t get why they grow where they grow, but we are off to a good start of a better understanding. Apparently, this seamount and the hydrodynamic conditions create a beneficial system for the sponges.’ A major finding located the sponge ground at the interface between two water masses where strong internal tidal waves can spread widely? and interact with the bottom landscape. The data from the sensors showed that the water flow at the summit of the seamount interacts with the seamount itself, producing turbulent conditions with temporarily high current speeds reaching up to 0.7 meter per second, which can be considered as “stormy” conditions in the deep sea.

At the same time, water movements around the seamount supply the sponge ground with food and nutrients from water layers above and below. The team measured the amount of food sinking from the surface to the sponge grounds and found that in this vertical direction, fresh food was delivered only once during a major event in the summer when the phytoplankton bloomed. Hanz: ‘This isn’t enough to sustain the sponge grounds, which is why we expect that additionally, bacteria and dissolved matter keep the sponges and associated fauna from starving.

Extreme environment

The long-term record shows that the sponges on Schulz Bank thrive at temperatures around zero degrees Celsius. This is at least 4 °C lower than stony cold-water corals that are also found in the deep sea. Hanz: ‘It is striking that they are alive with temperatures at zero degrees or even less. This is quite extreme, even for the deep sea.’ In this food-deprived environment, the cold might actually play a role in the sponge’s survival by lowering its metabolism. And the cold isn’t the only extremity they face. Video recordings of the highest current speed events in winter show that these ‘storms’ further push the sponges to their limit. Hanz: ‘The speeds that we witnessed, might be close to the maximum that they can endure. At the highest speed, we saw some sponges as well as anemones being ripped from the seafloor.’

And the most remarkable thing after watching hundreds of hours of footage? Hanz: ‘The image that I started with was almost the same as the image in the end. One year had gone by and everything looked almost the same. It’s just so cold out there that no crazy things are going on. The reef is still very pristine.’ However, Hanz and Mienis stress that it is a very vulnerable ecosystem. Hanz: ‘Sponges can be up to two hundred years old, once damaged it takes ages for them to recover.’ And there are potential threats. Hanz: ‘Fishery seems to be the biggest one, but there is also the future possibility of deep-sea mining and changes in temperature and turbulence caused by climate change. Mienis: ‘It is a fragile equilibrium that consists of many tiny components. Take one of those away and the whole system can collapse.’ Their research contributes to a first baseline that might become essential in future protection. Mienis: ‘We now identified the first natural ranges, and gathered a bit of the information on how these rich sponge grounds can thrive.’

###

Media Contact

NIOZ Communicatie

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.