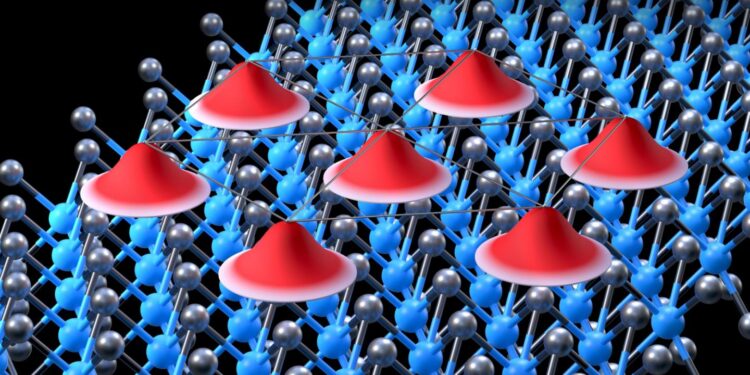

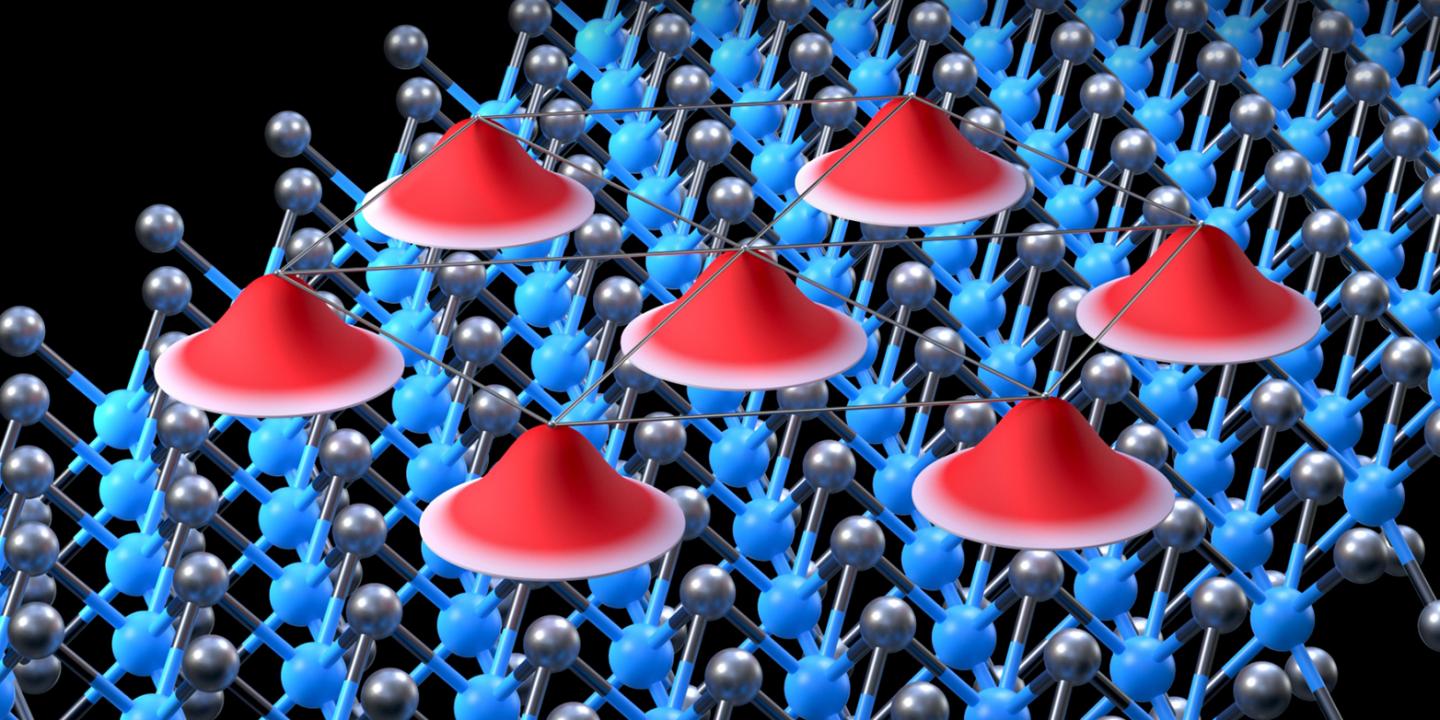

Credit: ETH Zurich

Crystals have fascinated people through the ages. Who hasn’t admired the complex patterns of a snowflake at some point, or the perfectly symmetrical surfaces of a rock crystal The magic doesn’t stop even if one knows that all this results from a simple interplay of attraction and repulsion between atoms and electrons. A team of researchers led by Atac Imamoglu, professor at the Institute for Quantum Electronics at ETH Zurich, have now produced a very special crystal. Unlike normal crystals, it consists exclusively of electrons. In doing so, they have confirmed a theoretical prediction that was made almost ninety years ago and which has since been regarded as a kind of holy grail of condensed matter physics. Their results were recently published in the scientific journal “Nature“.

A decades-old prediction

“What got us excited about this problem is its simplicity”, says Imamoglu. Already in 1934 Eugene Wigner, one of the founders of the theory of symmetries in quantum mechanics, showed that electrons in a material could theoretically arrange themselves in regular, crystal-like patterns because of their mutual electrical repulsion. The reasoning behind this is quite simple: if the energy of the electrical repulsion between the electrons is larger than their motional energy, they will arrange themselves in such a way that their total energy is as small as possible.

For several decades, however, this prediction remained purely theoretical, as those “Wigner crystals” can only form under extreme conditions such as low temperatures and a very small number of free electrons in the material. This is in part because electrons are many thousands of times lighter than atoms, which means that their motional energy in a regular arrangement is typically much larger than the electrostatic energy due to the interaction between the electrons.

Electrons in a plane

To overcome those obstacles, Imamoglu and his collaborators chose a wafer-thin layer of the semiconductor material molybdenum diselenide that is just one atom thick and in which, therefore, electrons can only move in a plane. The researchers could vary the number of free electrons by applying a voltage to two transparent graphene electrodes, between which the semiconductor is sandwiched. According to theoretical considerations the electrical properties of molybdenum diselenide should favour the formation of a Wigner crystal – provided that the whole apparatus is cooled down to a few degrees above the absolute zero of minus 273.15 degrees Celsius.

However, just producing a Wigner crystal is not quite enough. “The next problem was to demonstrate that we actually had Wigner crystals in our apparatus”, says Tomasz Smolenski, who is the lead author of the publication and works as a postdoc in Imamoglu’s laboratory. The separation between the electrons was calculated to be around 20 nanometres, or roughly thirty times smaller than the wavelength of visible light and hence impossible to resolve even with the best microscopes.

Detection through excitons

Using a trick, the physicists managed to make the regular arrangement of the electrons visible despite that small separation in the crystal lattice. To do so, they used light of a particular frequency to excite so-called excitons in the semiconductor layer. Excitons are pairs of electrons and “holes” that result from a missing electron in an energy level of the material. The precise light frequency for the creation of such excitons and the speed at which they move depend both on the properties of the material and on the interaction with other electrons in the material – with a Wigner crystal, for instance.

The periodic arrangement of the electrons in the crystal gives rise to an effect that can sometimes be seen on television. When a bicycle or a car goes faster and faster, above a certain velocity the wheels appear to stand still and then to turn in the opposite direction. This is because the camera takes a snapshot of the wheel every 40 milliseconds. If in that time the regularly spaced spokes of the wheel have moved by exactly the distance between the spokes, the wheel seems not to turn anymore. Similarly, in the presence of a Wigner crystal, moving excitons appear stationary provided they are moving at a certain velocity determined by the separation of the electrons in the crystal lattice.

First direct observation

“A group of theoretical physicists led by Eugene Demler of Harvard University, who is moving to ETH this year, had calculated theoretically how that effect should show up in the observed excitation frequencies of the excitons – and that’s exactly what we observed in the lab”, Imamoglu says. In contrast to previous experiments based on planar semiconductors, in which Wigner crystals were observed indirectly through current measurements, this is a direct confirmation of the regular arrangement of the electrons in the crystal. In the future, with their new method Imamoglu and his colleagues hope to investigate exactly how Wigner crystals form out of a disordered “liquid” of electrons.

###

Reference

Smolenski, T., Dolgirev, P.E., Kuhlenkamp, C. et al. Signatures of Wigner crystal of electrons in a monolayer semiconductor. Nature 595, 53-57 (2021). https:/

Media Contact

Ataç Imamoglu

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/

Related Journal Article

http://dx.