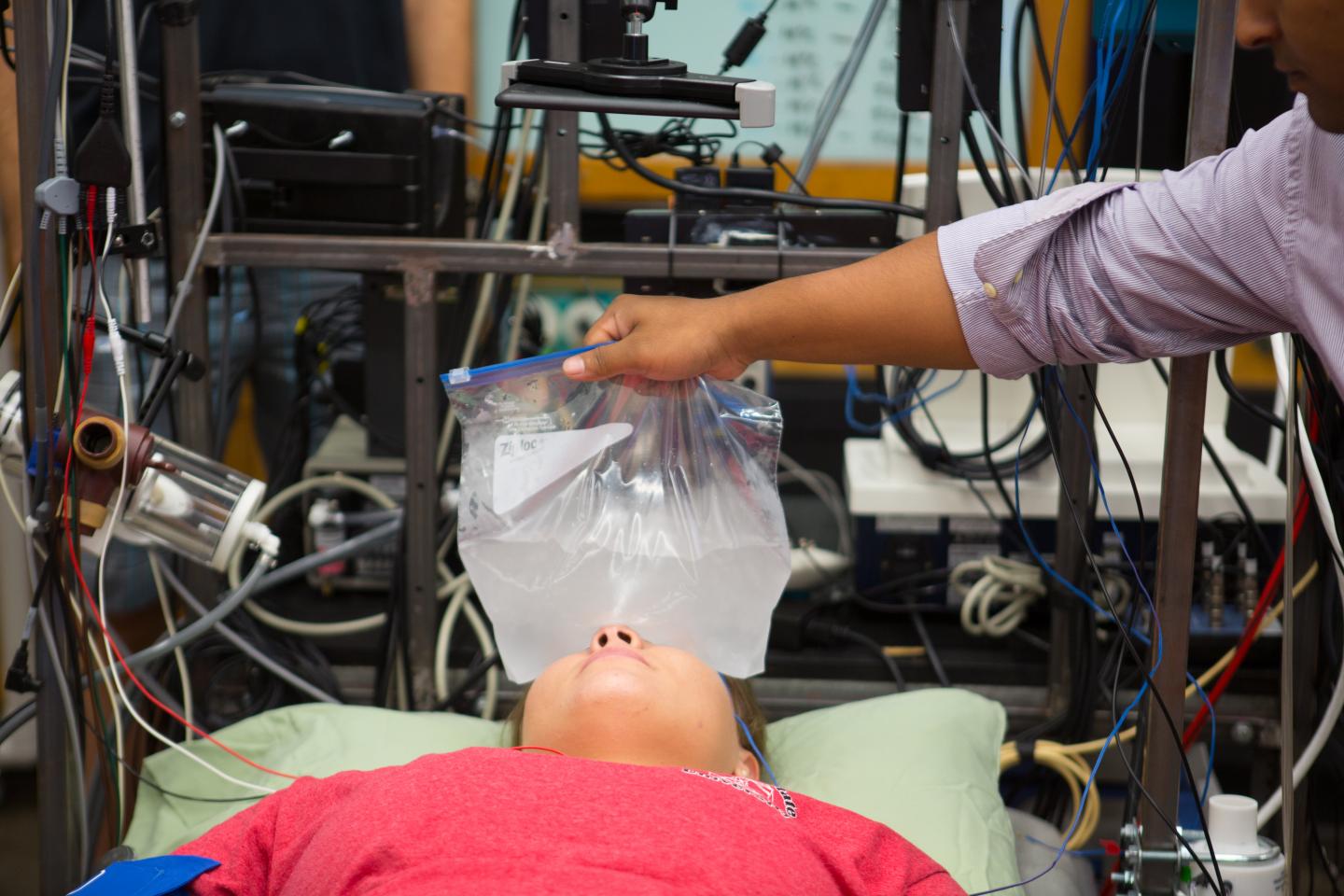

Credit: Douglas Levere, University at Buffalo

BUFFALO, N.Y. — A physiological process used commonly by mammals like seals and dolphins inspired the potentially life-saving method University at Buffalo researchers successfully tested to raise blood pressure in a simulation of trauma victims experiencing blood loss.

The pre-hospital intervention is simple — place a bag of ice on the victim's forehead, eyes and cheeks. In a small study, this method was shown to increase and maintain a person's blood pressure during simulated blood loss. The researchers have presented these findings at several recent conferences, and their paper will be published in a peer-reviewed journal later this year.

"There is a slight reduction in blood pressure during the simulation and we wanted to see if face cooling would reverse that. It turns out, it does. It raises blood pressure during a simulated hemorrhage situation," said Zachary Schlader, the study's lead author and an assistant professor of exercise and nutrition sciences in UB's School of Public Health and Health Professions.

Mammals like seals and dolphins — and, to a much lesser extent, humans — have what's called the "mammalian diving reflex." It's a physiological function that the animals employ for submersion in water.

During the reflex, which is partially activated when the face is immersed in cold water, certain bodily functions temporarily change to conserve oxygen, allowing the animals to remain underwater for long periods of time.

"The idea is, can we utilize a physiological phenomenon to have practical benefit? We're talking about pre-hospital interventions, so it has to be quick and easy for EMTs, military medics and other first responders," Schlader, PhD, said.

"We're not changing paradigms. But the biggest thing is, no one's ever put two and two together. No one's said I wonder if this could be used as a tool in clinical practice as opposed to simply a tool to probe physiology," he added.

Face cooling works because it constricts the blood vessels, which sends blood back to the heart, increasing blood output from the heart. The result is increased blood pressure.

Researchers tested their theory in UB's Center for Research and Education in Special Environments (CRESE) using 10 healthy participants. The team simulated blood loss in the study participants through a non-invasive process called "lower body negative pressure" (LBNP).

Participants were placed in a tube-shaped LBNP device resembling a CAT scan machine. A pump sucks air from the device to create negative pressure inside. As a result, blood is pulled to the person's legs from the upper body, simulating a hemorrhage event akin to tourniquet-controlled blood loss.

After six minutes of this, researchers placed a plastic baggy filled with ice water on the participant's forehead, eyes and cheeks for 15 minutes and then monitored whether blood pressure was elevated and maintained. The temperature of the ice water slurry was about freezing. "Think of it as brain freeze times 10," Schlader says. "It's not very comfortable, but it could buy you another 15 minutes."

The current study builds off previous research conducted by paper co-author Blair Johnson, an assistant professor of exercise and nutrition sciences at UB, who, like Schlader, is also a CRESE investigator.

"We were discussing that if you cool the forehead and the eyes, you evoke the mammalian diving reflex. And we thought, what if we can use that reflex to help bump up blood pressure during a hemorrhagic injury?" Johnson, PhD, said.

Schlader and his team plan to continue pursuing funding for future studies, one of which would examine whether chemical ice packs have the same effect on blood pressure as the ice water slurry.

What is clear is the need for this type of research. Trauma is the No. 1 cause of death in people under 40, Schlader says. In addition, hemorrhage is the leading cause of trauma deaths in the general population and the leading cause of preventable deaths on the battlefield.

"There's a need to figure out how to prolong survival in instances of severe blood loss. What it comes down to is maintaining blood pressure. As you lose more blood, you compromise your ability to maintain blood pressure," Schlader said.

Several interventions have been proposed previously, but these have proven to be less effective and not as practical for civilian and military applications as the face cooling method, Schlader said.

###

UB exercise science PhD candidate James Sackett and UB master of public health graduate Suman Sarker are also co-authors on the paper. Seed funding for the study was provided by the university's Innovative Micro-Programs Accelerating Collaboration in Themes (IMPACT) fund.

Media Contact

David Hill

[email protected]

716-645-4651

@UBNewsSource

http://www.buffalo.edu

Original Source

http://www.buffalo.edu/news/releases/2017/07/013.html