A University of Colorado Cancer Center study published in the journal Breast Cancer Research and Treatment shows that breast cancer patients whose health insurance plans included prescription drug benefits were 10 percent more likely to start important hormonal therapy than patients who did not have prescription drug coverage. Women with household income below $40,000 were less than half as likely as women with annual household income greater than $70,000 to continue hormonal therapy. Hormonal therapy for patients with estrogen- or progesterone-positive breast cancers can reduce the risk of cancer recurrence by as much as 50 percent.

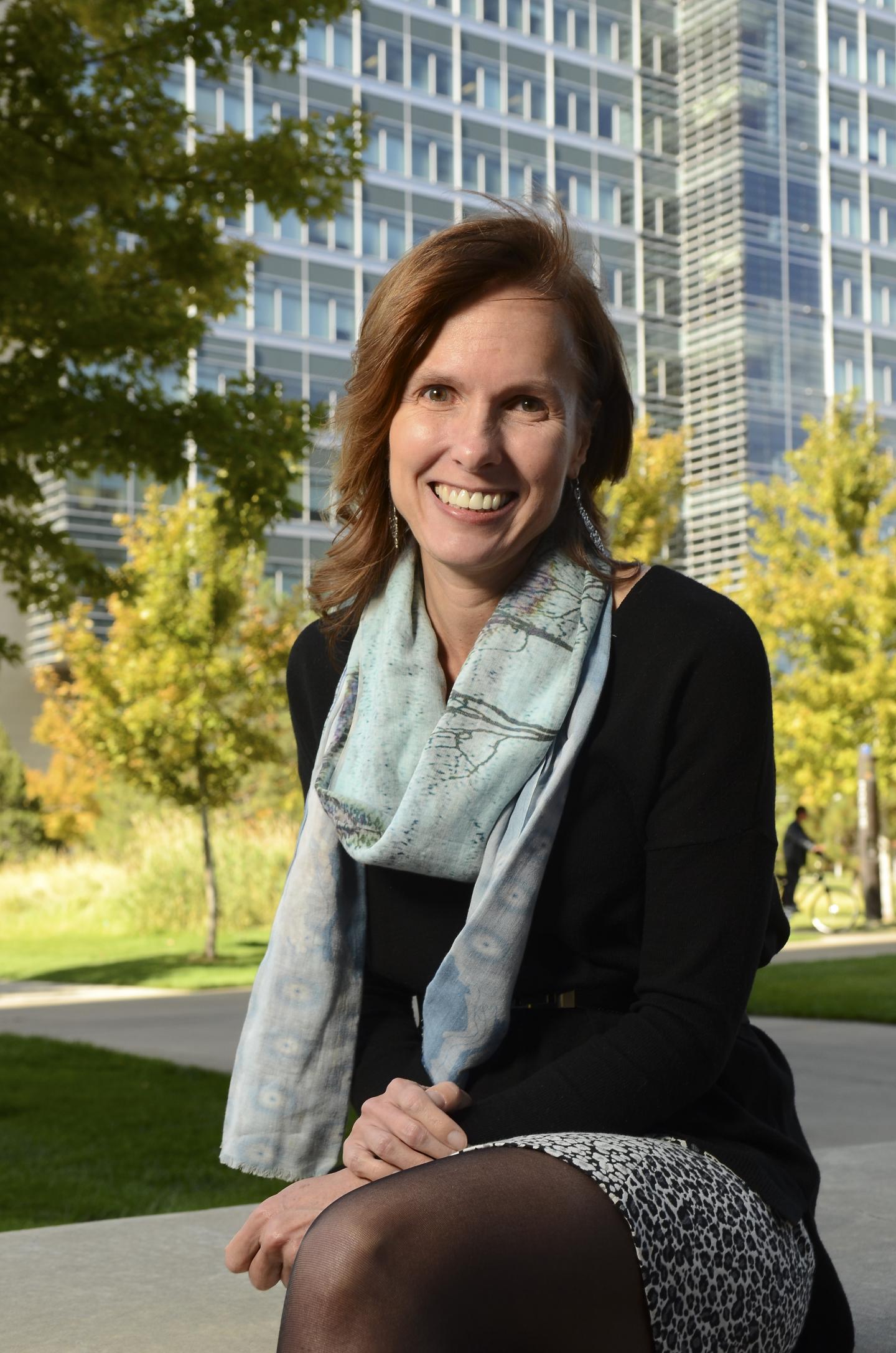

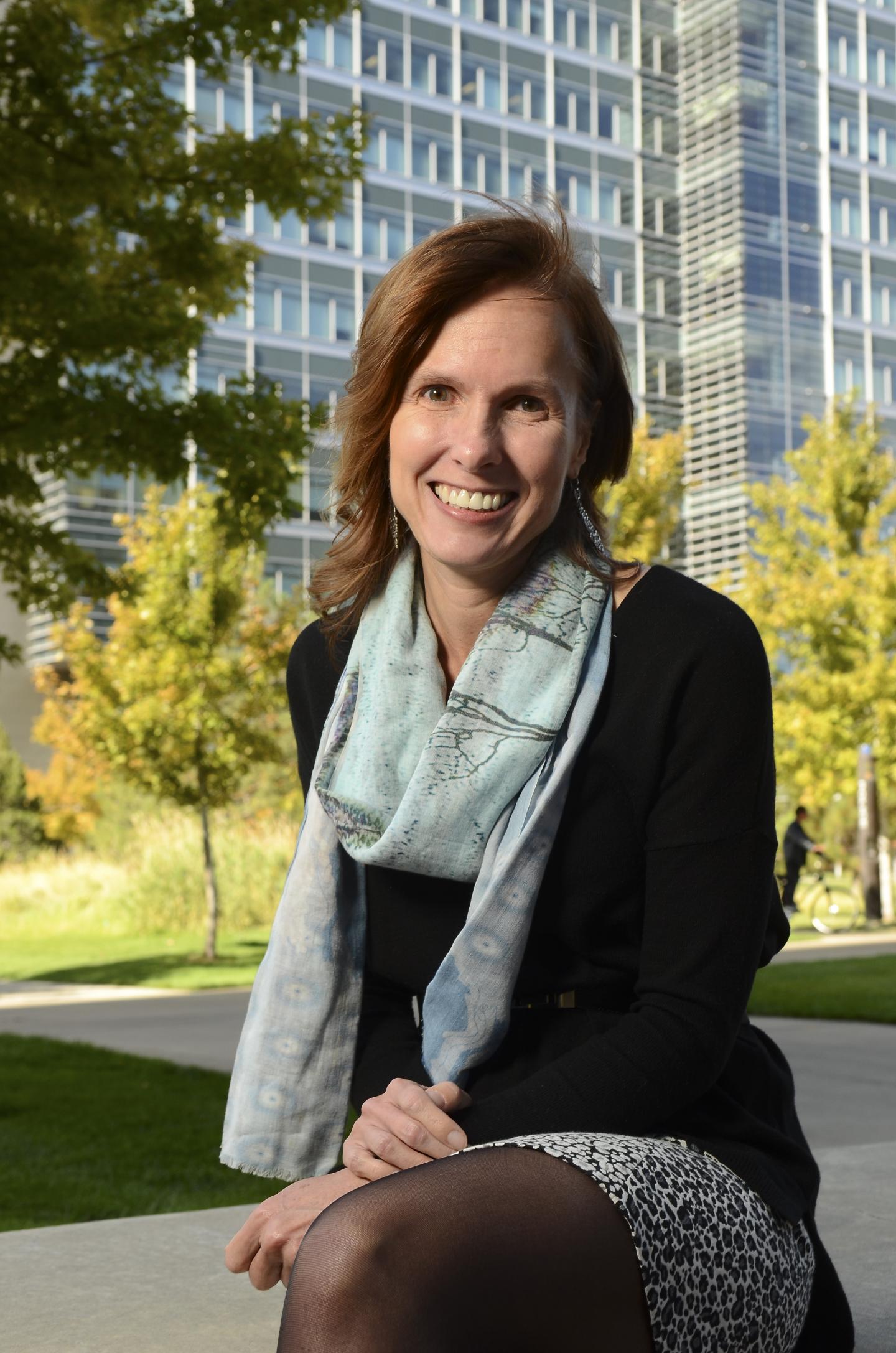

"I think what this research says is that general health insurance isn't enough. You have to have prescription drug coverage," says Cathy J. Bradley, PhD, associate director for Population Studies at the CU Cancer Center, professor in the Colorado School of Public Health, and the paper's first author.

The study used surveys to explore the initiation and continuation of prescribed hormonal therapy, reaching 712 women 9 months after a breast cancer diagnosis and then again 4 years later (this maintenance therapy generally lasts 5-10 years). Of women with prescription drug coverage, 90 percent started recommended hormonal therapy and 81 percent continued through the study. Of women without prescription drug coverage, 82 percent started hormonal therapy and 66 percent continued. Women with annual household income of less than $40,000 were only about 40 percent as likely as women from wealthier households to follow through with a doctor's recommendation to start hormonal therapy.

The study takes place in the context of two important changes to the landscape of oncology treatment: the development of new, targeted treatments for cancer, which tend to be very expensive and also tend to be taken orally and in patients' homes, and the Affordable Care Act, which has increased access to health insurance.

"Targeted cancer therapies tend to come in the form of pills taken at home. Many of these new therapies are expensive. This combination of more expensive medicines taken outside the hospital setting means less compliance. Or we see people choosing to alter their prescribed regimens by skipping doses. When you start to dial back from recommended doses, at some point the drug loses its effectiveness," Bradley says.

Bradley points to increasing costs of cancer care as a reason for insurers and healthcare consumers to rethink the definition of "catastrophic" illness. Her findings show that women without prescription drug coverage, especially if they are from low-income households, may choose not to comply even with a relatively low-cost treatment regimen.

"When someone thinks about coverage for high cost care, they're usually thinking about that trip to the hospital that costs $80,000 that could leave them bankrupt. But the fact is that the cost of prescription medicines–even fairly low cost medications – can also be 'catastrophic'," Bradley says.

She also notes that efforts under the Affordable Care Act are underway to provide prescription coverage that would guard against undue financial hardship in the case that expensive medicines become necessary.

"We have good evidence that when people feel that a drug is too expensive, they stop taking it," Bradley says. "This study suggests that reluctance to insure prescription drugs may result in increased recurrence and poor survival among women with breast cancer, one of the largest groups of cancer survivors."

###