A new study by a University of Texas at Arlington physics team in collaboration with bioengineering and psychology researchers shows for the first time how a small area of the brain can be optically stimulated to control pain.

Samarendra Mohanty, an assistant professor of physics, leads the Biophysics and Physiology Lab in the UT Arlington College of Science. He is co-author on a paper published online Wednesday by the journal PLOS ONE.

Samarendra Mohanty, an assistant professor of physics, leads the Biophysics and Physiology Lab in the UT Arlington College of Science. Photo Credit: UT Arlington

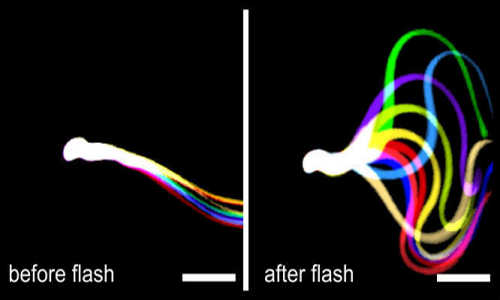

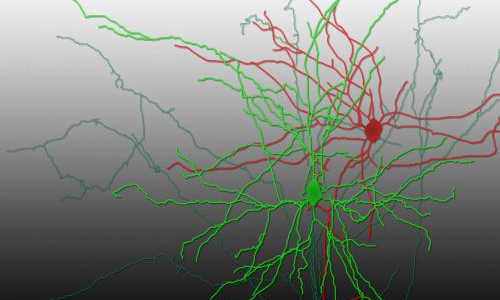

Researchers found that by using specific frequency of light to modulate a very small region of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex, or ACC, they could considerably lessen pain in laboratory mice. Existing electrode based ACC stimulation lacks specificity and leads to activation of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons.

“Our results clearly demonstrate, for the first time, that optogenetic stimulation of inhibitory neurons in ACC leads to decreased neuronal activity and a dramatic reduction of pain behavior,” Mohanty said. “Moreover, we confirmed optical modulation of specific electrophysiological responses from different neuronal units in the thalamus part of the brain, in response to particular types of pain-stimuli.”

The research focused on chemical irritants and mechanical pain, such as that experienced following a pinprick or pinch. Mohanty said the results could lead to increased understanding of pain pathways and strategies for managing chronic pain, which often leads to severe impairment of normal psychological and physical functions.

“While reducing the sensation for chronic pain by optical stimulation, we still want to sense certain types of pain because they tell us to move our hands or legs away from something that is too hot or that might otherwise hurt us if we get too close,” Mohanty said.

Young-tae Kim, a UT Arlington associate professor of bioengineering and study co-author, said the research could “possibly lead to less invasive methods for treating more severe types of pain without losing important emotional, sensing and behavioral functions.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Texas at Arlington.