According to a generally-accepted model of synaptic plasticity, a neuron that communicates with others of the same kind emits an electrical impulse as well as activating its synapses transiently.

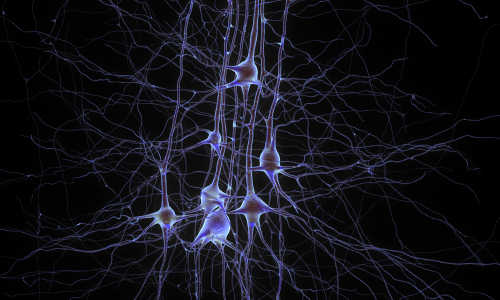

This is a group of neurons. Photo Credit: EPFL/Human Brain Project

This electrical pulse, combined with the signal received from other neurons, acts to stimulate the synapses. How is it that some neurons are caught up in the communication interplay even when they are barely connected? This is the chicken-or-egg puzzle of synaptic plasticity that a team at UNIGE is aiming to solve.

When we learn, we associate a sensory experience either with other stimuli or with a certain type of behavior. The neurons in the cerebral cortex that transmit the information modify the synaptic connections that they have with the other neurons. According to a generally-accepted model of synaptic plasticity, a neuron that communicates with others of the same kind emits an electrical impulse as well as activating its synapses transiently. This electrical pulse, combined with the signal received from other neurons, acts to stimulate the synapses. How is it that some neurons are caught up in the communication interplay even when they are barely connected? This is the crucial chicken-or-egg puzzle of synaptic plasticity that a team led by Anthony Holtmaat, professor in the Department of Basic Neurosciences in the Faculty of Medicine at UNIGE, is aiming to solve.

The results of their research into memory in silent neurons can be found in the latest edition of Nature.

Learning and memory are governed by a mechanism of sustainable synaptic strengthening. When we embark on a learning experience, our brain associates a sensory experience either with other stimuli or with a certain form of behavior. The neurons in the cerebral cortex responsible for ensuring the transmission of the relevant information, then modify the synaptic connections that they have with other neurons. This is the very arrangement that subsequently enables the brain to optimize the way information is processed when it is met again, as well as predicting its consequences.

Neuroscientists typically induce electrical pulses in the neurons artificially in order to perform research on synaptic mechanisms.

The neuroscientists from UNIGE, however, chose a different approach in their attempt to discover what happens naturally in the neurons when they receive sensory stimuli. They observed the cerebral cortices of mice whose whiskers were repeatedly stimulated mechanically without an artificially-induced electrical pulse. The rodents use their whiskers as a sensor for navigating and interacting; they are, therefore, a key element for perception in mice.

An extremely low signal is enough

By observing these natural stimuli, professor Holtmaat’s team was able to demonstrate that sensory stimulus alone can generate long-term synaptic strengthening without the neuron discharging either an induced or natural electrical pulse. As a result – and contrary to what was previously believed – the synapses will be strengthened even when the neurons involved in a stimulus remain silent.In addition, if the sensory stimulation lasts over time, the synapses become so strong that the neuron in turn is activated and becomes fully engaged in the neural network. Once activated, the neuron can then further strengthen the synapses in a forwards and backwards movement. These findings could solve the brain’s “What came first?” mystery, as they make it possible to examine all the synaptic pathways that contribute to memory, rather than focusing on whether it is the synapsis or the neuron that activates the other.

The entire brain is mobilized

A second discovery lay in store for the researchers. During the same experiment, they were also able to establish that the stimuli that were most effective in strengthening the synapses came from secondary, non-cortical brain regions rather than major cortical pathways (which convey actual sensory information). Accordingly, storing information would simply require the co-activation of several synaptic pathways in the neuron, even if the latter remains silent. These findings may also have important implications both for the way we understand learning mechanisms and for therapeutic possibilities, in particular for rehabilitation following a stroke or in neurodegenerative disorders. As professor Holtmaat explains: “It is possible that sensory stimulation, when combined with another activity (motor activity, for example), works better for strengthening synaptic connections”. The professor concludes: “In the context of therapy, you could combine two different stimuli as a way of enhancing the effectiveness.”

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Geneva.