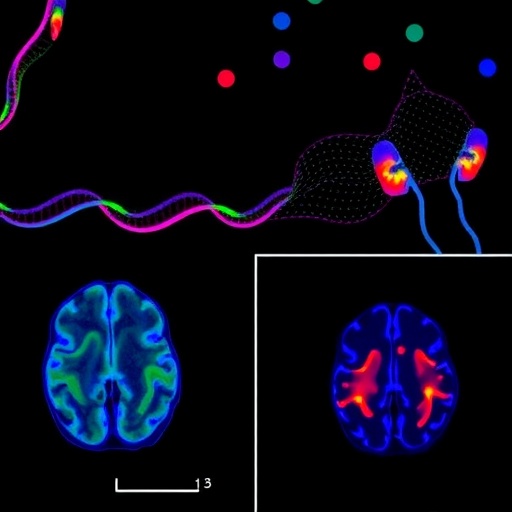

For decades, the medical community has viewed Multiple Sclerosis as a relentless storm of the immune system attacking the protective sheaths of the brain, yet a profound mystery remained regarding why the disease continues to worsen even when clinical inflammation is suppressed. Recent groundbreaking research published in Experimental & Molecular Medicine by researchers Blenkle, Geladaris, and Weber has finally pulled back the curtain on this enigma, focusing on the dark side of the brain’s own resident immune cells. Known as microglia, these once-ignored cells are now being identified as the primary architects of disease progression, shifting the entire paradigm of how we understand neurodegeneration in the human central nervous system. This study does not merely observe; it utilizes high-fidelity human in vitro models to pinpoint how these cells transition from protectors to silent killers, offering a glimpse into a future where the steady decline of MS patients can finally be halted.

The core of this scientific breakthrough lies in the realization that while current MS therapies are exceptionally effective at preventing relapses, they often fail to address the underlying, smoldering progression that leads to long-term disability. The researchers argue that this progression is driven by a state of chronic activation within the microglia, which creates a toxic environment that prevents the natural repair of myelin and leads to the irreversible death of neurons. By developing sophisticated human-based laboratory models, the team has managed to mimic the complex microenvironment of the MS brain, allowing them to observe the subtle molecular shifts that occur during the transition to progressive stages. This approach bypasses the limitations of traditional animal models, providing a direct and more accurate window into the specific biological pathways that define the human experience of this devastating neurological condition.

One of the most striking technical revelations of this research is the identification of distinct transcriptomic signatures that characterize “disease-associated microglia,” which appear to lose their homeostatic functions in favor of a pro-inflammatory profile. These cells begin to express a specific set of genes that trigger the release of reactive oxygen species and neurotoxic cytokines, which effectively dissolve the connections between brain cells over time. The study highlights that these changes are not random but follow a predictable molecular trajectory that can be intercepted with the right therapeutic strategy. By mapping these pathways with such precision, the research team has opened up a treasure trove of potential drug targets that were previously invisible to scientists. This marks a significant shift from broad immunosuppression to highly targeted neuroprotection, focusing on the specific metabolic and genetic switches that control microglial behavior.

Furthermore, the study delves into the fascinating world of therapeutic engagement, demonstrating that it is possible to “re-program” these rogue microglia back into an anti-inflammatory or regenerative state. Using their human in vitro models, the scientists tested various compounds that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and directly influence microglial signaling, showing that the damage is not necessarily inevitable. This emphasizes the role of precision medicine in neurology, where a patient’s unique microglial profile could eventually dictate their treatment plan. The ability to manipulate these cells in a controlled environment allows researchers to screen for drugs that specifically inhibit the destructive enzymes while sparing the cells’ vital roles in maintaining brain health. This delicate balance is the holy grail of neuroimmunology, and this research provides the most detailed roadmap toward achieving it to date.

The technical complexity of the human in vitro models used in this study cannot be overstated, as they incorporate induced pluripotent stem cells to create a living replica of human brain tissue. This allows the researchers to observe the interactions between microglia and other vital cells like astrocytes and neurons in real-time, providing a holistic view of the neurodegenerative process. By simulating the inflammatory conditions of a progressive MS brain, they have been able to identify the exact moment when microglial cells stop helping and start harming. This level of detail is crucial for clinical translation, as it ensures that the findings are directly relevant to human patients rather than being lost in translation between species. The sophistication of these models represents a new era in biomedical research where the human brain is no longer a “black box” but a system that can be modeled and modulated.

Another critical aspect of the findings is the role of metabolic reprogramming within these immune cells, as the researchers discovered that progressive MS microglia undergo a shift in how they generate energy. This metabolic “switch” is what empowers them to remain in a chronically active state for years, fueled by a process known as glycolysis rather than the more efficient oxidative phosphorylation. By targeting the enzymes that facilitate this inefficient energy production, the researchers suggest that we could effectively “starve” the neuroinflammatory response without harming the rest of the body’s immune system. This insight is revolutionary because it suggests that MS progression is as much a metabolic disorder within the brain as it is an immunological one. It provides a concrete biological mechanism for why the disease feels so relentless and offers a tangible target for long-term stabilization.

As we look toward the future of neurology, the implications of this study reach far beyond Multiple Sclerosis, potentially offering clues for other neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, where microglia are also implicated. The viral significance of this research lies in its promise to end the era of “hidden” progression, where patients felt their bodies failing despite being told their scans showed no new inflammation. By placing microglia at the center of the narrative, Blenkle and her colleagues have validated the lived experience of thousands of patients while providing the scientific community with the tools to change that experience forever. The study stands as a bold testament to the power of human-centric research and the incredible potential of biotechnology to solve the most complex puzzles of the human mind. It is a clarion call for a new generation of therapies that protect the soul of the brain by managing its most intimate defenders.

The researchers also highlight the importance of the extracellular matrix and how its degradation by microglia contributes to a feedback loop that sustains inflammation. In a healthy brain, the environment surrounding the cells provides structural support and signals that keep immune cells in check, but in the progressive MS brain, this matrix is dismantled, reinforcing the microglial dysfunction. This discovery suggests that future treatments might need to be multi-faceted, not only targeting the cells themselves but also repairing the structural integrity of the brain tissue. By understanding the mechanical and chemical cues that drive this feedback loop, scientists can develop therapies that “reset” the brain environment, making it hospitable for repair and inhospitable for degeneration. This holistic view of the brain as an ecosystem is a major theme of the paper and represents the cutting edge of modern neuroscience.

Technically, the study identifies specific molecules such as CCL2 and various interleukins that act as the primary messengers for this microglial destruction, providing a clear list of “villains” for pharmaceutical development. The research demonstrates that blocking these specific signals can prevent the recruitment of more inflammatory cells to the site of injury, effectively containing the “fire” of progression before it spreads to healthy areas of the brain. The ability to visualize these microscopic interactions in a laboratory setting has transformed our understanding from abstract concepts into concrete biological processes that can be measured and manipulated. This is the difference between guessing how a disease works and actually seeing the gears turn, and it represents a massive leap forward in the fight against chronic disability. The researchers’ use of high-throughput screening on these human models further accelerates the timeline for bringing these discoveries from the lab bench to the patient’s bedside.

Moreover, the study addresses the paradoxical nature of microglia, which are actually essential for the repair of myelin, the insulating layer that allows nerves to transmit signals. When MS progression occurs, these cells lose their ability to clear away myelin debris, which acts as a barrier to the cells that could actually fix the damage. The researchers show that by therapeutically engaging certain receptors on the microglia, they can restore this “garbage collection” function, essentially clearing the way for the brain to heal itself. This dual approach—stopping the damage and facilitating the repair—is the hallmark of the therapeutic strategy proposed in this work. It shifts the goal of MS treatment from simply slowing down the decline to actively promoting recovery and restoration of lost function, a hope that was previously thought to be impossible for those in the advanced stages of the disease.

The international scientific community is already buzzing about the potential for these human in vitro models to replace traditional animal testing in the early stages of drug development. Because these models are derived from human cells, they avoid the biological inconsistencies that often lead to drug failure in human clinical trials. This efficiency could shave years off the development process for new MS drugs, bringing life-changing treatments to patients much faster than ever before. The viral nature of this discovery is tied to this sense of urgency and the feeling that we are on the precipice of a major victory in medicine. The researchers emphasize that the speed of progress in this field is now limited only by our ability to fund and scale these advanced modeling techniques, as the biological targets have been identified and the path forward is clear.

In analyzing the specific genetic triggers mentioned in the paper, it becomes clear that the team has identified a “master switch” for microglial aggression. This genetic regulatory network appears to be controlled by a small group of transcription factors that, when suppressed, can neutralize the entire inflammatory program of the cell. This is perhaps the most exciting technical detail of the study, as it suggests that we don’t need to block dozens of different symptoms but can instead turn off the source of the problem at its genetic core. The precision of this approach would likely minimize side effects, as it specifically targets the pathological state of the cell rather than interfering with its healthy biological functions. It is a masterclass in modern molecular biology and a shining example of how deep-dive genetic research can yield practical, world-changing results.

Finally, the study touches on the psychological impact of these findings for the MS community, providing a sense of hope that is grounded in rigorous, verifiable science. For too long, the progression of MS felt like an invisible ghost, something that couldn’t be seen on an MRI but could be felt in the increasing difficulty of walking or thinking. By giving this “ghost” a name—microglial-associated progression—and a biological face, the researchers have reclaimed the narrative of the disease. The paper concludes with a powerful call to action for the integration of these human in vitro models into standard drug discovery pipelines, ensuring that the next generation of MS therapies is built on the most accurate possible understanding of human biology. This is not just a scientific paper; it is a manifesto for a new way of treating the human brain and a promise of a future where MS no longer means a slow loss of self.

As we move into 2026 and beyond, the work of Blenkle, Geladaris, and Weber will undoubtedly be cited as a turning point in the history of neurology. Their ability to synthesize complex genetic data with practical therapeutic applications has set a new bar for what is possible in the field of neuroimmunology. The tech-heavy approach of using stem-cell-derived brain models has proven that we no longer need to rely on approximations; we can now study the human brain with the precision it deserves. This research is a viral sensation because it speaks to the universal human desire to conquer the diseases that steal our independence and our quality of life. Through the lens of these microscopic cells, we are finally seeing the big picture of how to protect the human nervous system from the inside out, turning the tide in the battle against Multiple Sclerosis for millions of people worldwide.

Subject of Research: The role of microglia in the progression of Multiple Sclerosis and the development of human in vitro models for therapeutic targeting.

Article Title: Microglia-associated progression of multiple sclerosis: target identification and therapeutic engagement in human in vitro models.

Article References:

Blenkle, A., Geladaris, A. & Weber, M.S. Microglia-associated progression of multiple sclerosis: target identification and therapeutic engagement in human in vitro models.

Exp Mol Med (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-026-01647-w

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: 10.1038/s12276-026-01647-w

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis, Microglia, Neurodegeneration, Human In Vitro Models, Therapeutic Targeting, Neuroimmunology, Myelin Repair, Progressive MS.

Tags: chronic inflammation in MS progressionexperimental research in multiple sclerosishalting MS disease progressionhuman in vitro models in MS researchimmune system and neurodegenerationinnovative therapies for multiple sclerosismicroglia in multiple sclerosisneuroinflammation and neurodegeneration connectionparadigm shift in multiple sclerosis treatmentrole of microglia in chronic diseasetargeting microglia for neuroprotectionunderstanding resident immune cells in the brain