In a striking challenge to long-held assumptions about brain organization, new research reveals that the precise spatial positioning of neurons may not be as critical to their function as previously believed. A study published in Nature Neuroscience by Roig-Puiggros et al. explores how neurons displaced beneath the cortical surface—known as heterotopic neurons—retain their molecular identity, connectivity, and function, despite their abnormal location. This breakthrough adds a new layer of complexity to our understanding of brain architecture, suggesting that equivalent neural circuits can be constructed in distinct spatial arrangements, potentially reshaping theories on brain evolution and developmental neurobiology.

Neuronal positioning within the brain has traditionally been considered fundamental for circuit formation and function. The cerebral cortex, known for its intricate laminar and columnar architecture, is organized with remarkable precision, where neuron types are thought to be intrinsically linked to their specific cortical layers or regions. However, the extent to which the physical location of neurons constrains their identity and operational circuitry has remained enigmatic. This question gains urgency given the myriad brain structures across species, which vary greatly in their architectural configurations yet maintain comparable functional outcomes.

The investigative team turned to a genetically modified mouse model deficient in Eml1, a gene vital for proper neuronal migration during brain development. In these Eml1 knockout mice, many neurons fail to reach their intended cortical layers and instead form ectopic clusters beneath the cortex, widely referred to as heterotopia. These clusters serve as a natural platform to interrogate whether positional disruption impacts the neurons’ molecular profiles and their ability to forge appropriate neural networks. Previous literature had identified such heterotopias but lacked a comprehensive functional or molecular characterization.

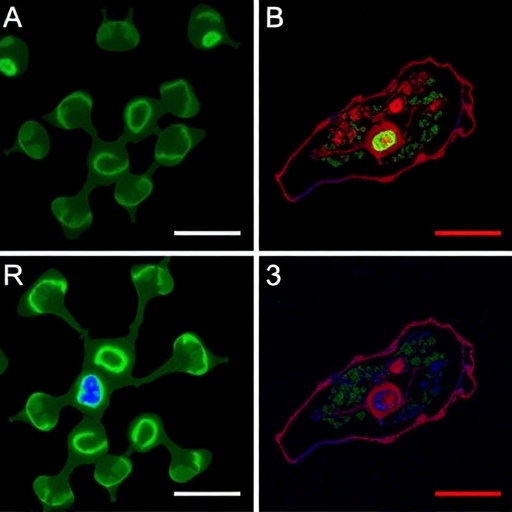

Using molecular profiling techniques, the researchers discovered that heterotopic neurons remarkably preserved their expected molecular signatures corresponding to their putative cortical layers. Despite their mislocation, these neurons maintained their transcriptional identities, expressing characteristic markers that aligned with their functional roles within the cortex. This finding contradicts the notion that positional cues are the sole or primary determinants of neuronal identity. Instead, intrinsic genetic programs appear to guide molecular identity, even in the face of anatomical misplacement.

Beyond molecular profiling, the study delved into the connectivity patterns of heterotopic neurons. Advanced tracing methodologies revealed that these misplaced neurons established long-range connections typical of their cortical counterparts. They formed axonal projections to appropriate target regions, suggesting that wiring specificity is preserved independently of spatial context. The preservation of these circuits indicates a robustness in developmental programs that can compensate for displacement and maintain essential communication pathways in the brain.

Electrophysiological recordings further illuminated the functional cohesion of heterotopic neurons. Measurements showed that these neurons fired in coordinated patterns analogous to those observed in normal cortical neurons. The heterotopic neuronal populations displayed synchronized activity, underscoring their integration into functional ensembles. These coherent electrical properties are crucial for sensory processing and higher-order cognitive functions, reinforcing that heterotopias are not mere anatomical anomalies but active components of neural computation.

Crucially, the research probed the role of heterotopic neurons in sensory information processing. Using somatosensory paradigms, the team demonstrated that these neurons organized themselves into sensory-processing centers that mirrored the topographic arrangement found in the neocortex. Somatotopic maps—spatial representations of sensory input locations on the body—were conserved within the heterotopias, allowing these misplaced neurons to respond selectively to tactile stimuli. This preservation of sensory mapping highlights the possibility that functional architectures can arise in noncanonical brain territories.

A particularly compelling facet of the research involved cortical silencing experiments. By selectively inhibiting activity in the overlying cortical layers, researchers assessed whether sensory discrimination depended on the conventional cortical circuitry or on the heterotopic neurons beneath. Unlike expectations, sensory discrimination remained intact during cortical silencing, implicating the heterotopic neurons as the primary drivers of this function. This groundbreaking observation unveils a previously unrecognized adaptability in sensory processing circuits, where displaced neuronal populations can independently underpin perceptual capabilities.

The implications of this study extend far beyond mouse models. Brain organization varies drastically across the animal kingdom, with species exhibiting diverse cortical and subcortical architectures yet achieving comparable sensory and cognitive functions. The revelation that equivalent circuits can develop in different spatial configurations opens new avenues for understanding how evolution might mold brain structures. It suggests a flexibility in circuit assembly that could accommodate environmental pressures, genetic variation, and developmental perturbations, enhancing the robustness of brain function across species.

Moreover, these findings may have profound consequences for neurological and developmental disorders characterized by aberrant neuronal migration and heterotopia formation. Conditions such as epilepsy and certain forms of intellectual disability are linked to cortical malformations, including misplaced neuronal clusters. Understanding that heterotopic neurons can retain function and connectivity encourages reevaluation of their potential contributions to pathology and neural plasticity. Therapeutic strategies might leverage this intrinsic organizational capability for circuit repair or functional restoration.

From a developmental neuroscience perspective, the preservation of molecular identity and circuit integration in heterotopias underscores the potency of intrinsic genetic and molecular programs in neuron specification. While the extracellular environment and positional signals undoubtedly influence brain patterning, this research demonstrates that cell-intrinsic determinants can override spatial displacement effects. This insight challenges classical developmental models reliant heavily on positional information and calls for a reassessment of how neuronal fate and connectivity are programmed.

Technically, the multidisciplinary approach combining genetic manipulation, molecular analysis, connectivity mapping, electrophysiology, and behavior represents a tour de force in modern neuroscience. The precise tracing of axonal projections alongside in vivo recordings and functional assays provides a comprehensive picture of neuronal identity and functionality despite anomalous localization. This integrative methodology sets a benchmark for future investigations into brain plasticity, development, and evolution.

In conclusion, Roig-Puiggros and colleagues have unveiled a remarkable degree of functional and molecular resilience within the neocortical system. Their results decisively show that neocortical neuron identity, connectivity, and sensory function can emerge independently of exact spatial positioning. This paradigm shifts how neuroscience views the relationship between brain structure and function, illustrating that spatial constraints are not as absolute as once thought. Instead, multiple architectural configurations can support convergent functional outcomes, explaining the diversity of brain morphologies seen across the animal kingdom.

This study heralds a new era of exploration into the principles of brain assembly, offering hope for understanding brain development disorders and inspiring novel bioengineering approaches for building functional circuits. The position-independent emergence of neural identity and functionality underscores nature’s adaptability, revealing that the brain’s blueprint is robustly encoded within the neurons themselves, not just their physical arrangement. As the field delves deeper, these insights pave the way for unlocking mysteries of cognition and consciousness rooted in the architecture and function of our most enigmatic organ—the brain.

Subject of Research: Neuronal positioning, molecular identity, connectivity, and function in neocortical neurons using an Eml1 knockout mouse model.

Article Title: Position-independent emergence of neocortical neuron molecular identity, connectivity and function.

Article References:

Roig-Puiggros, S., Guyoton, M., Suchkov, D. et al. Position-independent emergence of neocortical neuron molecular identity, connectivity and function. Nat Neurosci (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02142-7

Image Credits: AI Generated

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-025-02142-7

Tags: brain architecture and evolutionbrain structure across speciescerebral cortex organizationchallenges to traditional neuroscience theoriesdevelopmental neurobiology breakthroughsgenetic influences on neuron identityheterotopic neurons and brain functionimplications for brain researchmolecular identity of neuronsneocortical neuron identityneuronal positioning and circuit formationunderstanding neural connectivity