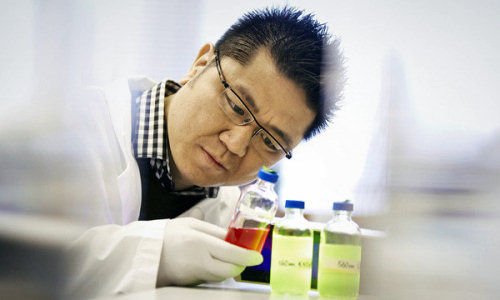

A team of researchers at the University of Toronto has discovered a method of assembling “building blocks” of gold nanoparticles as the vehicle to deliver cancer medications or cancer-identifying markers directly into cancerous tumors. The study, led by Warren Chan, Professor at the Institute of Biomaterials & Biomedical Engineering (IBBME) and the Donnelly Centre for Cellular & Biomolecular Research (CCBR), appears in an article in Nature Nanotechnology this week.

“To get materials into a tumor they need to be a certain size,” explains Chan. “Tumors are characterized by leaky vessels with holes roughly 50 — 500 nanometers in size, depending on the tumor type and stage. The goal is to deliver particles small enough to get through the holes and ‘hang out’ in the tumor’s space for the particles to treat or image the cancer. If particle is too large, it can’t get in, but if the particle is too small, it leaves the tumor very quickly.”

Chan and his researchers solved this problem by creating modular structures ‘glued’ together with DNA. “We’re using a ‘molecular assembly’ model — taking pieces of materials that we can now fabricate accurately and organizing them into precise architectures, like putting LEGO blocks together,” cites Leo Chou, a 5th year PhD student at IBBME and first author of the paper. Chou was awarded a 2012-13 Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation Ontario Region Fellowship for his work with nanotechnology.

“The major advantage of this design strategy is that it is highly modular, which allows you to ‘swap’ components in and out. This makes it very easy to create systems with multiple functions, or screen a large library of nanostructures for desirable biological behaviors,” he states.

The long-term risk of toxicity from particles that remain in the body, however, has been a serious challenge to nanomedical research.

“Imagine you’re a cancer patient in your 30s,” describes Chan. “And you’ve had multiple injections of these metal particles. By the time you’re in your mid-40s these are likely to be retained in your system and could potentially cause other problems.”

DNA, though, is flexible, and over time, the body’s natural enzymes cause the DNA to degrade, and the assemblage breaks apart. The body then eliminates the smaller particles safely and easily.

But while the researchers are excited about this breakthrough, Chan cautions that a great deal more needs to be known.

“We need to understand how DNA design influences the stability of things, and how a lack of stability might be helpful or not,” he argues.

“The use of assembly to build complex and smart nanotechnology for cancer applications is still in the very primitive stage of development. Still, it is very exciting to be able to see and test the different nano-configurations for cancer applications,” Chan adds.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by University of Toronto, Erin Vollick.