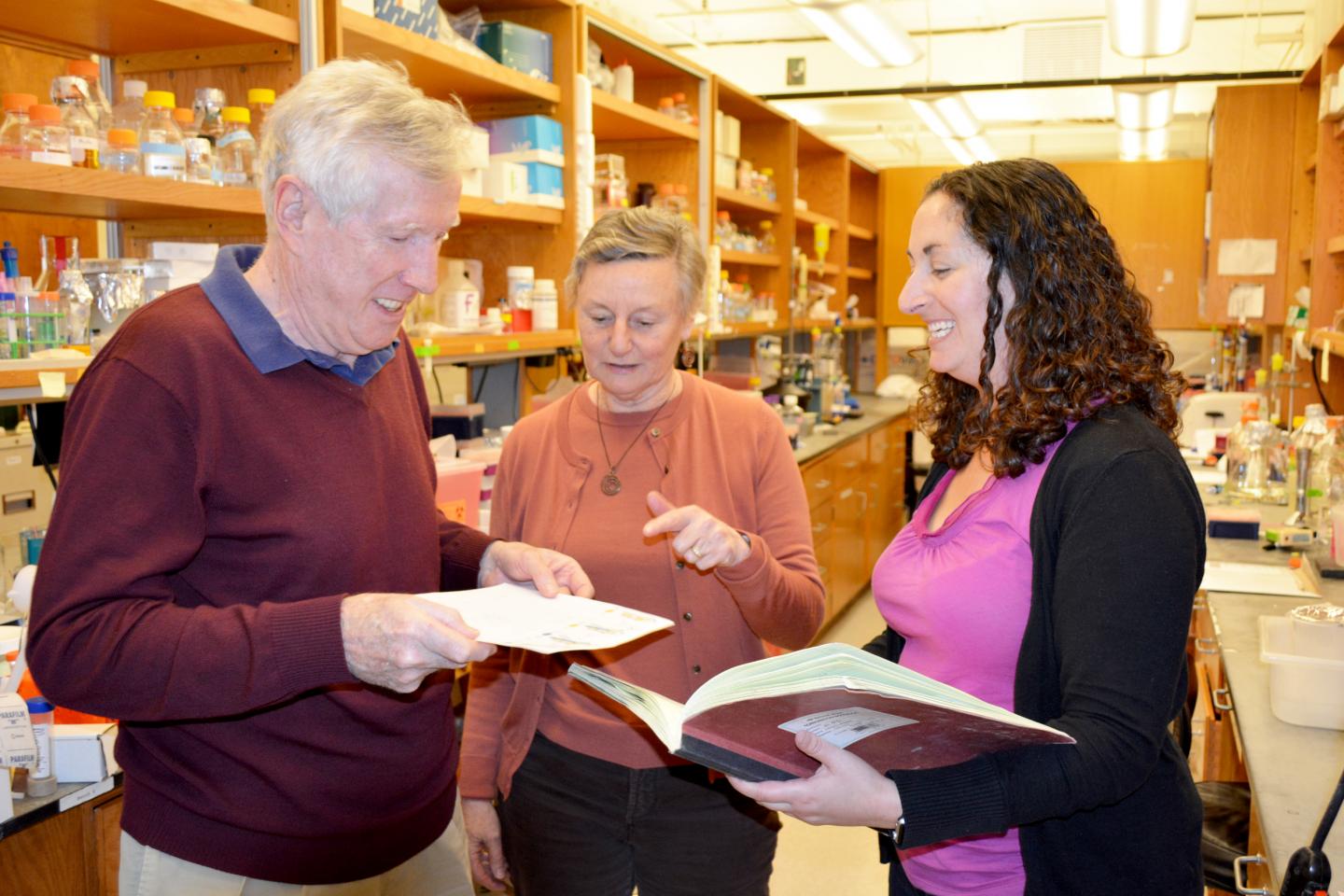

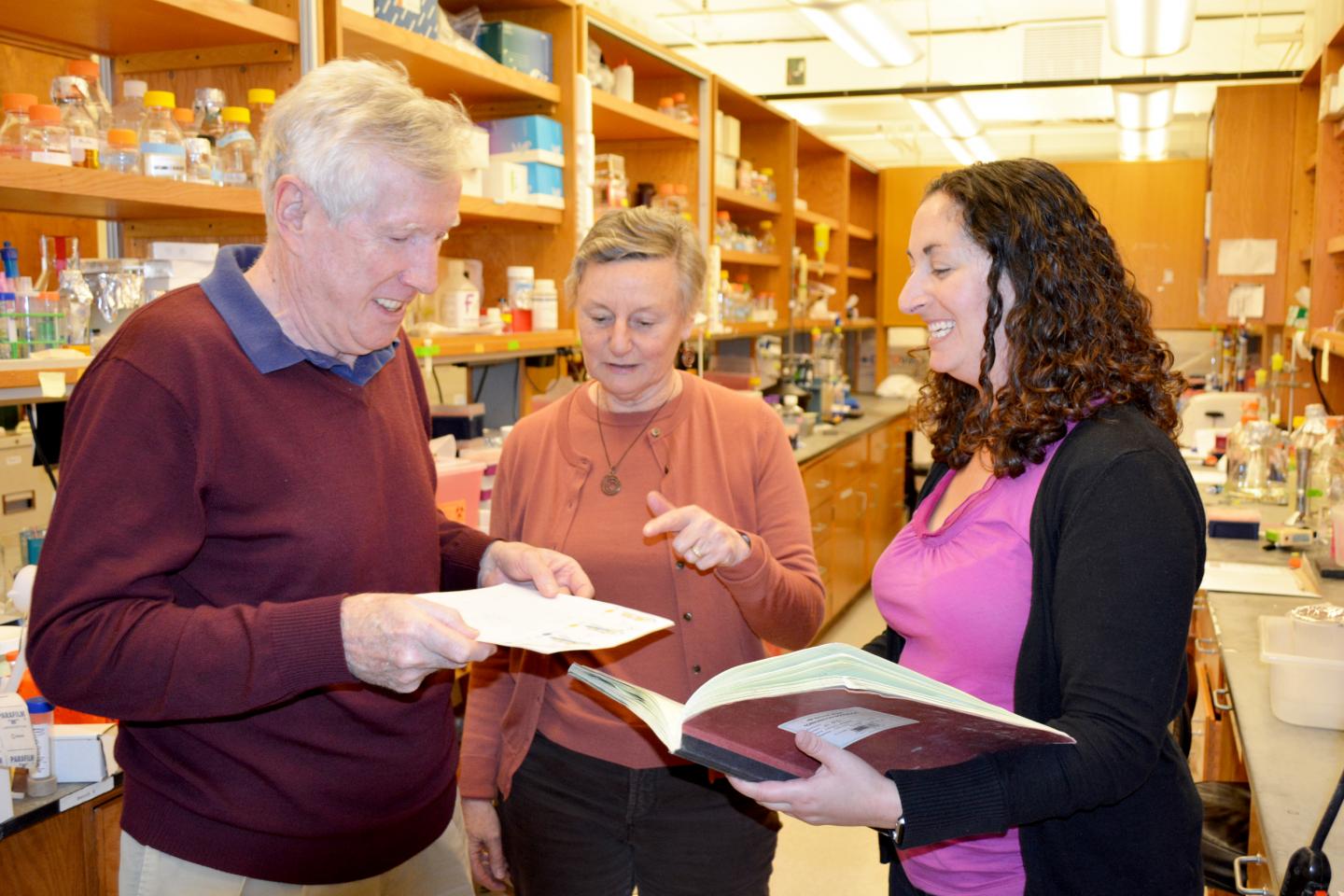

Credit: The Scripps Research Institute

LA JOLLA, CA – March 8, 2017 – Research findings that first had scientists scratching their heads have turned out to be "quite revolutionary," according to study leaders at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI).

The scientists found that in a competition between two apparently equivalent proteins, one protein wins out every time as it swoops in to claim a cellular binding target. This protein is of special interest to researchers because it can trigger cancer cells to kill themselves. In fact, the researchers now hope future therapeutics that mimic this protein may work as potential cancer drugs.

"This work at the molecular level has a real potential to benefit patients," said TSRI Research Associate Rebecca Berlow, first author of the new study, published online today in the journal Nature.

A Puzzling Finding

Human cells, including cancer cells, can activate a set of genes that enable them to go into "survival mode" when deprived of an oxygen-carrying blood supply. This mode switches on when a protein called HIF1α binds to a part, called TAZ1, of a second protein, called CBP.

Cells have an "off" switch too. To turn off the "hypoxic response" to low oxygen, a protein called CITED2 jumps in to bind to TAZ1 when oxygen levels go back to normal.

As intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), neither HIF1α nor CITED2 folds into a stable shape by itself; instead, these domains remain unstructured, ready to change conformations to wedge themselves into the right binding site on TAZ1.

HIF1α and CITED2 have an equal affinity for TAZ1, and scientists didn't expect one to bind more effectively than the other. So TSRI Research Associate Rebecca Berlow was surprised to discover that, when forced to compete, CITED2 pushes HIF1α out of the way every time.

"This finding totally violated everything we know about equilibrium," said Berlow. "My first reaction was 'how did I mess this up?' "

CITED2's behavior seemed to contradict a tenet of thermodynamics that states that a system should become less ordered, not more organized over time. Obviously, something else was going on–but what?

Puzzled, Berlow presented her findings to TSRI Professor Peter Wright, Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Investigator at TSRI, and study co-author TSRI Professor Jane Dyson. They decided to investigate further. If the initial finding was correct, Wright realized, this would be "quite revolutionary."

CITED2 Has a Hidden Superpower

Berlow's initial findings weren't wrong–in fact, they revealed a new phenomenon in protein competition.

The researchers found that the system is not randomly becoming more organized. Rather, CITED2 appears to be the first example of a protein that uses its disordered shape, not its binding affinity, to win out.

"Discovering CITED2's ability to win these battles is a paradigm shift," said Wright, senior author of the new study.

Taking on Cancer

This finding could have implications for future cancer drugs. The researchers explained that past drug candidates have tried to interrupt the cancer cell survival mode by stopping HIF1α from ever reaching TAZ1, but they haven't been very effective. The new study suggests that it may be more efficient to mimic nature's own response and use a CITED2-like drug to knock HIF1α away.

"This is a very, very efficient switch," said Wright. "You only need a small amount of CITED2 to switch off the hypoxic response, and no amount of HIF1α can switch it back on."

Next, the researchers plan to study the detailed mechanisms that allow CITED2 to take over the TAZ1 binding site. They are also looking into the therapeutic potential of CITED2 in other diseases where HIF1α can intensify a dangerous low-oxygen response.

###

The study, "Hypersensitive termination of the hypoxic response by a disordered protein switch," was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant CA096865), the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Cancer Society (grant 125343-PF-13-202-01-DMC).

About The Scripps Research Institute

The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) is one of the world's largest independent, not-for-profit organizations focusing on research in the biomedical sciences. TSRI is internationally recognized for its contributions to science and health, including its role in laying the foundation for new treatments for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, and other diseases. An institution that evolved from the Scripps Metabolic Clinic founded by philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps in 1924, the institute now employs more than 2,500 people on its campuses in La Jolla, CA, and Jupiter, FL, where its renowned scientists–including two Nobel laureates and 20 members of the National Academies of Science, Engineering or Medicine–work toward their next discoveries. The institute's graduate program, which awards PhD degrees in biology and chemistry, ranks among the top ten of its kind in the nation. In October 2016, TSRI announced a strategic affiliation with the California Institute for Biomedical Research (Calibr), representing a renewed commitment to the discovery and development of new medicines to address unmet medical needs. For more information, see http://www.scripps.edu.

Media Contact

Madeline McCurry-Schmidt

[email protected]

858-784-9254

@scrippsresearch

http://www.scripps.edu

############

Story Source: Materials provided by Scienmag