Crop modification can be traced to the beginning of agriculture and human civilization.

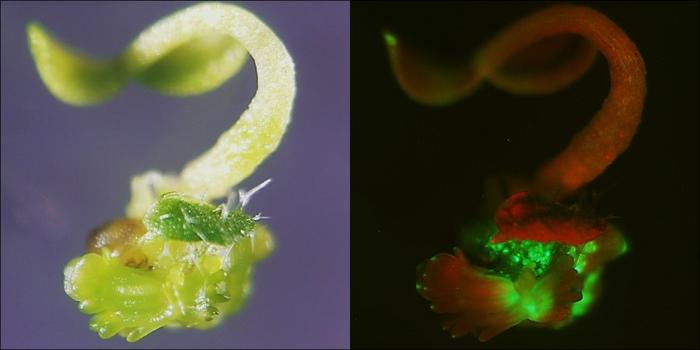

Credit: Photo courtesy of Basitaan Bargmann.

Crop modification can be traced to the beginning of agriculture and human civilization.

Native Americans, for example, developed corn from a wild grass called teosinte more than 7,000 years ago.

Methods to increase crop resiliency and sustainability have evolved, and improved, over time. Biotechnology, or the use of biology to develop new products and organisms, is an application that holds great promise for impactful changes to the agricultural systems. Through this method, the DNA in plant cells is modified — for instance so that crops require less water and fertilizer supplementation or are more tolerant to drought conditions and resistant to plant diseases — resulting in improved crop traits.

Although biotechnology has shown success in crop trait improvement, the process can be long and tedious, said Bastiaan Bargmann, assistant professor in the School for Plant and Environmental Sciences and an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute.

“A huge bottleneck in the implementation of biotechnology is that you have to be able to grow a whole plant back from the few cells where you’ve managed to change the DNA. This is called regeneration” he said. “We can change the DNA in a few cells, but then getting those cells to turn back into a whole plant can be quite challenging in many species.”

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Bargmann, the principal investigator, in partnership with researchers at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in Missouri, aims to enhance the efficiency of plant regeneration. The project will test the use of morphogenic factors to reprogram cell fate and steer it toward the formation of whole plants. The team was awarded a $1.2 million grant to aid in this research.

The bulk of the research, Bargmann said, will focus on the fundamental understanding of plant regeneration.

“To that end, we will perform studies in a model plant system, thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana), to better understand the cellular and molecular regulation of regeneration and identify factors that can enhance the process,” he said.

As a proof of concept, the team will then implement the use of such factors in wheat, a crop known to be difficult to transform and regenerate. Virginia Tech is well-known for its small grains breeding program, and the research team will partner with Assistant Professor Nicholas Santantonio, program leader, to apply this process on different wheat varieties.

In addition to the planned research, the research team will advance public understanding and youth involvement through the development of a lecture series for high school students in the Virginia Summer Residential Governor’s School for Agriculture titled “The Past, Present, and Future of Bioengineering for Crop Trait Improvement.”