Children with neuroblastoma – responsible for 15% of cancer deaths in this age group – could in future be given treatments with fewer side-effects than those associated with the current chemotherapy, thanks to a discovery by researchers at the University of Cambridge.

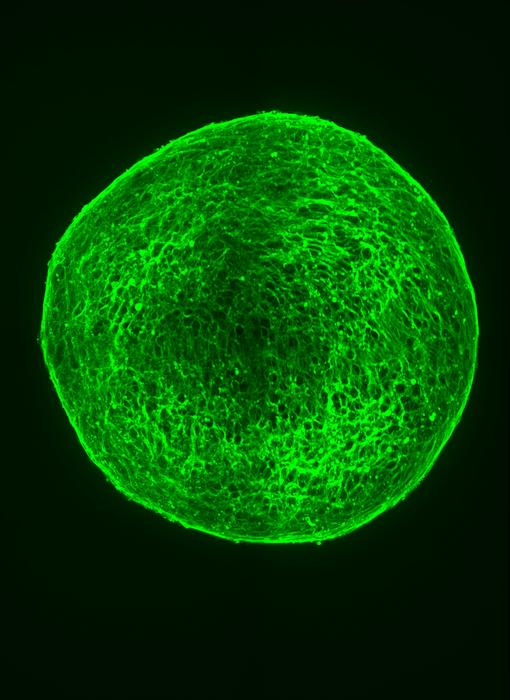

Credit: Kirsty Ferguson/Developmental Cell

Children with neuroblastoma – responsible for 15% of cancer deaths in this age group – could in future be given treatments with fewer side-effects than those associated with the current chemotherapy, thanks to a discovery by researchers at the University of Cambridge.

The approach involves the use of a ‘differentiation therapy’, a type of treatment that does not involve killing cancer cells, but instead involves encouraging cells to become normal non-dividing cells.

While this new research is still at an early stage and has yet to be trialled in patients, it involves a combination of two drugs already approved for use – palbociclib, a treatment used for certain types of breast cancers, and retinoic acid, used to treat neuroblastoma patients at most risk of relapse.

The findings of the study, funded by Cancer Research UK, are published today in Developmental Cell.

Neuroblastoma is the third most common cause of cancer deaths in children, after brain tumours and blood cancers. It arises in immature nerve cells known as neuroblasts, with around half of all neuroblastomas originating in the adrenal glands, which are located on top of the kidneys, and the remainder occurring in other areas of the abdomen, chest, neck or around the spine where nerve cells exist.

As the embryo develops, cells divide and replicate, migrating around the body, where they stop dividing and ‘differentiate’ into mature cell types, with chemical ‘switches’ attached to the DNA in cells turning its genes on and off and telling the cell how to behave.

Some of these cells go on to form the peripheral nervous system, which includes any nerves outside the brain. Occasionally this programming goes awry and the immature cells carry on dividing instead of forming mature neurons, leading to the development of neuroblastoma. The disease varies in its aggressiveness depending on the maturity of the cells within the tumour, with the most mature or differentiated tumours being the least aggressive, and the least differentiated tumours carrying the highest risk of relapse and death.

Professor Anna Philpott, who led the research at the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute at Cambridge, was inspired to study neuroblastoma after her niece was diagnosed with the disease as a child. Fortunately, unlike many children affected by this form of cancer, her niece’s story had a happy ending, and she is now a student in her twenties.

“I’ve seen first-hand how devastating this disease can be as it affects such young children and can be a particularly gruelling disease for families to manage,” said Professor Philpott, who is also a fellow at Clare College, Cambridge. “Its outcomes are very variable. Some children can be cured with surgery or chemotherapy, but others will need to receive a very high dose of chemotherapy – and some of them then relapse and require further treatment.”

Chemotherapy – while it can be effective – is a blunt instrument. It needs to kill cancer cells, but in doing so it can kill cells in other tissue, causing side effects. In neuroblastoma treatments, some of these side effects are relatively mild and many are temporary, though some can be life-threatening such as severe infections because of impaired immunity. There is also a significant risk of long-term complications including hearing impairment, growth restrictions and infertility. Some children can also develop second cancers as a result of the chemotherapy given to treat neuroblastoma.

Professor Philpott’s previous research had involved studying the normal development of nerve cells in tadpoles, but a chance encounter at a Cambridge seminar with a trustee of the patient charity Neuroblastoma UK made her realise that she could apply her findings to the condition that had affected her niece.

Joint first author Dr Kirsty Ferguson, a researcher at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute said: “From studies of normal development, we know that if you’re able to slow down cell division, then the cells’ programming begins to correct itself and they get back on track in terms of differentiating. We wanted to see if there was a way of encouraging this to happen in neuroblastoma cells.”

The team was able to show in a laboratory setting that treating neuroblastoma cells in a dish with palbociclib – already approved for front-line treatment of HR-positive and HER2-negative breast cancers – causes them to slow their division significantly and form mature nerves.

“Neuroblastoma cells don’t look like nerves, but more like round cells that divide very rapidly,” added Dr Ferguson. “But when we treated them with palbociclib, their division slowed down and they started to grow axons and dendrites, which was an indication to us that they were maturing into nerves.”

With collaborator Professor Louis Chesler from the Institute of Cancer Research, Sutton, they then used the drug to treat mice into which human neuroblastoma cells had been grafted, and found that it was able to significantly reduce tumour growth. The drug was also effective at extending lifespans in mice that had been genetically-altered to develop neuroblastoma.

But palbociclib was not enough to fully stop the growth of neuroblastoma. Although the cells looked like mature nerve cells, they continued to divide, only at a slower rate. To counter this, the team treated the cells in the dish with retinoic acid in addition to palbociclib. Retinoic acid is a drug currently used as a maintenance therapy for neuroblastoma patients at highest risk of relapse, and the team found that this stopped the division of neuroblastoma cells even more effectively.

Professor Philpott and her collaborators, including Professor Suzanne Turner in the Department of Pathology at Cambridge, have now received funding from the Medical Research Council and Cancer Research UK to continue their research, including testing the effect of the drug combination in mice prior to taking this to clinical trial in children.

Dr Sarah Gillen, joint first author and also from Professor Philpott’s lab, said: “Children will still need chemotherapy to kill the main tumour, but once that treatment is out of the way, we think the combination of palbociclib and retinoic acid should be enough to stop any remaining neuroblastoma cells in their tracks. And because these drugs don’t need to kill the tumour cells, only to guide them back to the right path, it should be a much kinder treatment with fewer side-effects.”

Professor Philpott added: “Because both of these drugs have already been shown to be safe in people – and one of them is already in use in children – the clinical trial process should be much faster. If it’s successful, then we could see this new treatment being used within the next decade.”

Dr Laura Danielson, Children’s and Young People’s Research Lead at Cancer Research UK, said: “Each year in the UK around 100 children are diagnosed with neuroblastoma. Better and less toxic treatments are needed to ensure more of these children survive and with a better quality of life.

“Although further studies are warranted, it is great to see this early research of a new therapy, or combination of therapies, that could potentially be beneficial in better treating neuroblastoma and with fewer side effects.”

Reference

Ferguson, KM & Gillen, SL et al. Palbococlib releases the latent differentiation capacity of neuroblastoma cells. Dev Cell; 20 Sept 2023; DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2023.08.028

Creative encounters with neuroblastoma patients and families

As well as carrying out her research into neuroblastoma, Dr Kirsty Ferguson writes poetry about her work as a way of engaging with patients and their families.

“It’s a really nice way of taking some quite technical science and turning it into a positive force for good and common understanding,” she said.

As part of Cambridge Creative Encounters for the 2023 Cambridge Festival, Dr Ferguson was inspired by patient and family stories from the charity Neuroblastoma UK as a basis for some of her poetry.

“I found some very powerful and moving stories which I combined into a poem to help others understand what it’s like to live through this condition,” she added. “The message ‘fly high’ speaks to children who are sadly no longer with us, those who have survived neuroblastoma and fly high despite side-effects, and families who continue to navigate this path alongside their children and courageously share their stories.”

Fly High

By Kirsty Ferguson – with many thanks to Neuroblastoma UK and all those who allowed their words to be shared, italicised throughout this poem.

None of us

had heard the word

neuroblastoma,

until that frightful day.

Just 18 months old,

Tumour size of a fist,

With ten per cent chance

of surviving, they say.

Then chemotherapy, surgery,

A stem cell transplant;

We were so proud

Of her fighting spirit.

Radio-,

Differentiation-,

Immuno-therapy;

And he never complained one bit.

This cancer –

It was relentless.

What would we fight

It with now?

There’s a lasting impact

When a child has cancer,

But we continue through,

Somehow.

My little angel

Slipped away that morning,

As I whispered,

“I love you, fly high”.

Now up above,

With wings they spread,

Sparkles of hope

In the deep blue sky.

See everyone

needs a bit of hope,

Even just,

A tiny glimmer.

You never know the journey

Life will take you on –

Remember to look

For the things that shimmer.

Put your heart and soul

Into what you want to achieve –

Don’t let cancer

Hold you back.

I truly wish you

A future you deserve,

Fly high,

And never look back.

Journal

Developmental Cell

DOI

10.1016/j.devcel.2023.08.028

Method of Research

Experimental study

Subject of Research

Cells

Article Title

Palbococlib releases the latent differentiation capacity of neuroblastoma cells

Article Publication Date

20-Sep-2023