The most detailed study of a city’s waterways anywhere in the world has revealed how chemical pollutants in London’s rivers changed over the pandemic.

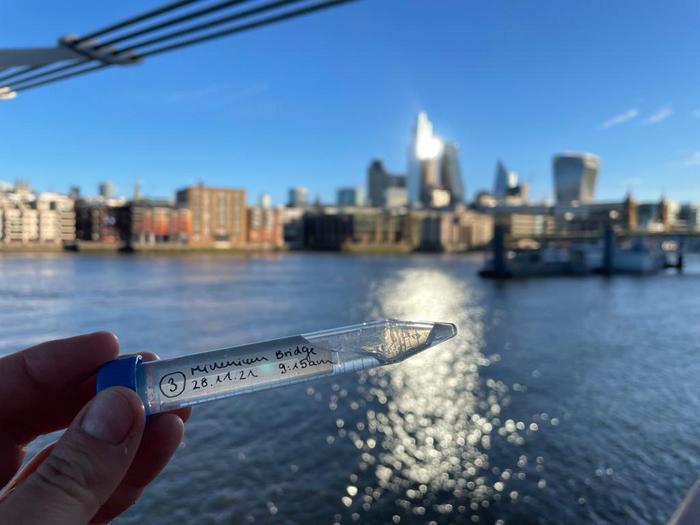

Credit: Melanie Egli / Imperial College London

The most detailed study of a city’s waterways anywhere in the world has revealed how chemical pollutants in London’s rivers changed over the pandemic.

In a study led by researchers at Imperial College London, scientists have shown how pollutants entering the capital’s river systems – including traces of prescription medications such as antibiotics and antidepressants – changed over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study, which involved hundreds of samples taken from 14 waterways in Greater London over three years,[1] focused particularly on how wastewater contaminates the city’s rivers and how this changed over the pandemic’s peak. The researchers believe their analysis, published in the journal Environment International, is by far the largest study globally tracking changes to contaminants in a major city’s river systems.[2]

It finds that during 2020 there was a significant decrease in traces of some types of pollutants, including pharmaceuticals, in the River Thames – the city’s main waterway. This coincided with national lockdowns and reduced numbers of people travelling or commuting into London. But levels of contaminants increased again significantly in 2021, with greater concentrations of antibiotics, anti-anxiety and anti-depressant medications entering the city’s waterways after restrictions were lifted.

The analysis also reveals that 21 of the compounds detected posed a potential risk to the environment in freshwater ecosystems, including antibiotics, pain medication and pet parasite medications.

The researchers explain they were able to differentiate between pollutants and pinpoint their sources along waterways with a high level of geographical resolution, and that wastewater treatment plants and combined sewer overflows were the main sources of chemical risks overall. In addition, the team also detected a wide range of other chemicals including illicit drugs and neonicotinoid pesticides used in pet tick and flea medications.

They also found that smaller rivers feeding into the River Thames were most impacted by wastewater pollution, from both direct release from wastewater treatment plants and combined sewer overflows (CSOs). They add that the scale of wastewater monitoring used in their study could be used to gauge the direct and indirect impacts of changes in human activity, and the impact of wastewater processing, on the health of our rivers.

Dr Leon Barron, part of the Environmental Research Group at Imperial College London and senior author of the study, said: “This is the largest study of a heavily urbanised river system and provides us with uniquely detailed insights into several aspects of London’s water quality, most notably how the concentration of pharmaceuticals in our water changed over the course of the pandemic – reflecting changes in public health and reduced movement of people to, from and within London during lockdowns.”

Melanie Egli, PhD student and first author of the study, said: “This study enabled us to gain insights not only into what chemical contamination was in our rivers, but also provided us with high

geographic resolution of where they are coming from. Crucially, we found that some small tributary rivers were particularly impacted by wastewater, highlighting the need for increased monitoring and infrastructure investment for their protection.”

Dr Barron added: “Aside from the pandemic, this work provides an important snapshot of chemical contamination before the Thames Tideway Tunnel ‘Super Sewer’ is opened in 2025, which aims to reduce pollution by over 95 %. This is a great start, but wastewater contamination in other rivers nationally needs urgent action.”

Professor Guy Woodward, Professor of Ecology in the Department of Life Sciences, and a co-author of the paper, commented: “This is a comprehensive and detailed study of the huge range of chemicals that we find in our freshwater ecosystems, and it picks up on several that are at potentially harmful concentrations for wildlife, but which have seemingly been overlooked in traditional surveys of our water quality in urban areas at this resolution.”

The research was supported by funding from the UKRI Medical Research Council (MRC) and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The study forms part of a project within the Environmental Research Group and the MRC Centre for Environment and Health at Imperial College London.

–

NOTES TO EDITORS: This press release uses a labelling system developed by the Academy of Medical Sciences to improve the communication of evidence. For more information, please see: http://www.sciencemediacentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/AMS-press-release-labelling-system-GUIDANCE.pdf

[1] River Thames, River Hogsmill, River Wandle, River Brent, River Crane, River Lee, River Lea, Channelsea River, Fray’s River, Grand Union Canal (Paddington Arm, Slough Arm), Pymmes Brook, and Beverley Brook

[2] Over the course of three years, from 2019 to 2021, researchers collected and analysed almost 400 water samples from Greater London waterways. Overall, they found almost 100 pollutants of concern, with each pollutant detected at least once.

Analysis revealed how these compounds changed over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Collection took place in the last three months of each year for consistency, and samples were taken by Melanie Egli, PhD student within the Environmental Research Group and the MRC Centre for Environment and Health at Imperial.

Using the 2019 data as a baseline, the team was able to detect statistical changes in the concentration of compounds. Analysis revealed the presence of three compounds classed as high-risk contaminants – posing a risk to the environment or increased antimicrobial resistance. These include imidacloprid (a parasiticide found principally in flea medications for domestic pets), azithromycin (an antibiotic), and diclofenac (an anti-inflammatory). The largest risk compound was imidacloprid, aligning with previous findings on the environmental impact of pet parasiticides.

In addition, the study found that despite an initial dip in compounds in 2020, by 2021, levels of many pharmaceutical compounds and metabolites had exceeded pre-pandemic levels (measured against the 20129 baseline). The findings match prescribing data trends, which show a year-on-year increase in the prescription of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications in England.

They also show the smaller rivers feeding into the Thames were the most impacted by wastewater pollution, released directly from wastewater treatment plants and combined sewage overflows (CSOs), with the city’s eight plants believed to be operating at 96% of their population capacity, and higher than the UK average (88%). Four rivers were most impacted by outputs from treatment plants and CSOs: the River Lea, Beverley Brook, River Wandle, and the Hogsmill River, all of which feed into the River Thames.

Journal

Environment International

DOI

10.1016/j.envint.2023.108210

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

‘A one-health environmental risk assessment of contaminants of emerging concern in London’s waterways throughout the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic’

Article Publication Date

20-Sep-2023