Super-thin planet nurseries have a boosted chance of forming big planets, according to a study announced this week at the Europlanet Science Congress (EPSC) 2022 in Granada, Spain. An international team, led by Dr Marion Villenave of NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), observed a remarkably thin disc of dust and gas around a young star, and found that its structure accelerated the process of grains clumping together to form planets.

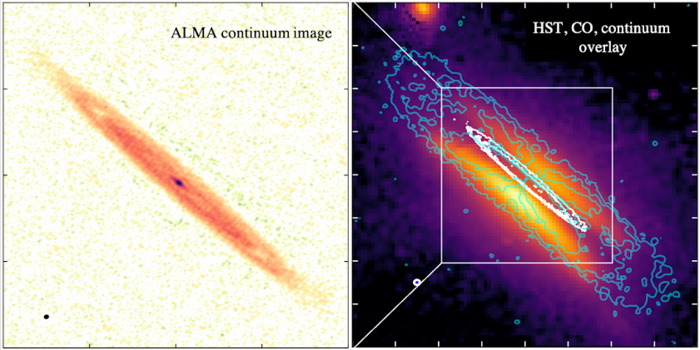

Credit: Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO) /Hubble/NASA/ESA /M. Villenave

Super-thin planet nurseries have a boosted chance of forming big planets, according to a study announced this week at the Europlanet Science Congress (EPSC) 2022 in Granada, Spain. An international team, led by Dr Marion Villenave of NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), observed a remarkably thin disc of dust and gas around a young star, and found that its structure accelerated the process of grains clumping together to form planets.

“Planets only have a limited opportunity to form before the disc of gas and dust, their nursery, is dissipated by radiation from their parent star. The initial micron-sized particles composing the disc must grow rapidly to larger millimetre-sized grains, the building blocks of planets. In this thin disc, we can see that the large particles have settled into a dense midplane, due to the combined effect of stellar gravity and interaction with the gas, creating conditions that are extremely favourable for planetary growth,” explained Dr Villenave.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the team obtained very high resolution images of the proto-planetary disc Oph163131, located in a nearby star-forming region called Ophiuchus. Their observations showed that, while disc is twice the diameter of our Solar System, at its outer edge the bulk of the dust is concentrated vertically in a layer only half the distance from Earth to the Sun. This makes it one of the thinnest planetary nurseries observed to date.

“Looking at proto-planetary discs edge-on gives a clear view of the vertical and radial dimensions, so that we can disentangle the dust evolution processes at work”, said Villenave. “ALMA gave us our first look at the distribution of millimetre-sized grains in this disc. Their concentration into such a thin layer was a surprise, as previous Hubble Space Telescope (HST) observations of finer, micron-sized particles showed a region extending almost 20 times higher.”

Simulations by the team based on the observations show that the seeds of gas-giant planets, which must be at least 10 Earth-masses, can form in the outer part of the disc in less than 10 million years. This is within the typical lifetime of a planetary nursery before it dissipates.

“Thin planet nurseries appear to be favourable for forming big planets, and may even facilitate planets forming at large distance from the central star,” said Villenave. “Finding further examples of these thin discs might help provide more insights into the dominant mechanisms for how wide-orbit planets form, a field of research where there are still many open questions.”