CAMBRIDGE, MA — Within the visual cortex of the adult brain, a small region is specialized to respond to faces, while nearby regions show strong preferences for bodies or for scenes such as landscapes.

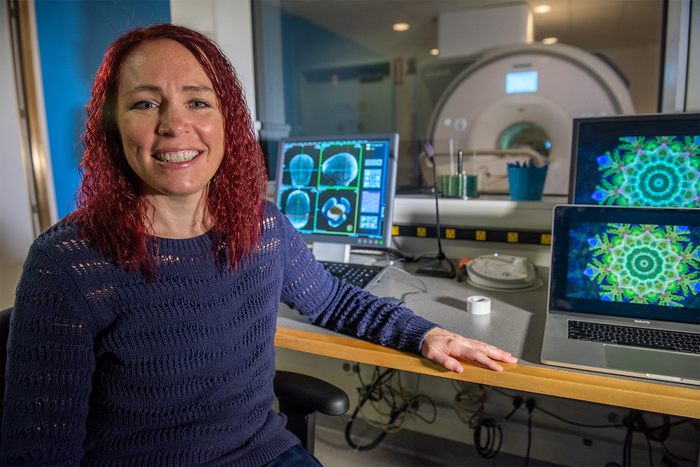

Credit: Kris Brewer

CAMBRIDGE, MA — Within the visual cortex of the adult brain, a small region is specialized to respond to faces, while nearby regions show strong preferences for bodies or for scenes such as landscapes.

Neuroscientists have long hypothesized that it takes many years of visual experience for these areas to develop in children. However, a new MIT study suggests that these regions form much earlier than previously thought. In a study of babies ranging in age from two to nine months, the researchers identified areas of the infant visual cortex that already show strong preferences for either faces, bodies, or scenes, just as they do in adults.

“These data push our picture of development, making babies’ brains look more similar to adults, in more ways, and earlier than we thought,” says Rebecca Saxe, the John W. Jarve Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, and the senior author of the new study.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers collected usable data from more than 50 infants, a far greater number than any research lab has been able to scan before. This allowed them to examine the infant visual cortex in a way that had not been possible until now.

“This is a result that’s going to make a lot of people have to really grapple with their understanding of the infant brain, the starting point of development, and development itself,” says Heather Kosakowski, an MIT graduate student and the lead author of the study, which appears today in Current Biology.

Distinctive regions

More than 20 years ago, Nancy Kanwisher, the Walter A. Rosenblith Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT, used fMRI to discover the fusiform face area: a small region of the visual cortex that responds much more strongly to faces than any other kind of visual input.

Since then, Kanwisher and her colleagues have also identified parts of the visual cortex that respond to bodies (the extrastriate body area, or EBA), and scenes (the parahippocampal place area, or PPA).

“There is this set of functionally very distinctive regions that are present in more or less the same place in pretty much every adult,” says Kanwisher, who is also a member of MIT’s Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines, and an author of the new study. “That raises all these questions about how these regions develop. How do they get there, and how do you build a brain that has such similar structure in each person?”

One way to try to answer those questions is to investigate when these highly selective regions first develop in the brain. A longstanding hypothesis is that it takes several years of visual experience for these regions to gradually become selective for their specific targets. Scientists who study the visual cortex have found similar selectivity patterns in children as young as 4 or 5 years old, but there have been few studies of children younger than that.

In 2017, Saxe and one of her graduate students, Ben Deen, reported the first successful use of fMRI to study the brains of awake infants. That study, which included data from nine babies, suggested that while infants did have areas that respond to faces and scenes, those regions were not yet highly selective. For example, the fusiform face area did not show a strong preference for human faces over every other kind of input, including human bodies or the faces of other animals.

However, that study was limited by the small number of subjects, and also by its reliance on an fMRI coil that the researchers had developed especially for babies, which did not offer as high-resolution imaging as the coils used for adults.

For the new study, the researchers wanted to try to get better data, from more babies. They built a new scanner that is more comfortable for babies and also more powerful, with resolution similar to that of fMRI scanners used to study the adult brain.

After going into the specialized scanner, along with a parent, the babies watched videos that showed either faces, body parts such as kicking feet or waving hands, objects such as toys, or natural scenes such as mountains.

The researchers recruited nearly 90 babies for the study, collected usable fMRI data from 52, half of which contributed higher-resolution data collected using the new coil. Their analysis revealed that specific regions of the infant visual cortex show highly selective responses to faces, body parts, and natural scenes, in the same locations where those responses are seen in the adult brain. The selectivity for natural scenes, however, was not as strong as for faces or body parts.

The infant brain

The findings suggest that scientists’ conception of how the infant brain develops may need to be revised to accommodate the observation that these specialized regions start to resemble those of adults sooner than anyone had expected.

“The thing that is so exciting about these data is that they revolutionize the way we understand the infant brain,” Kosakowski says. “A lot of theories have grown up in the field of visual neuroscience to accommodate the view that you need years of development for these specialized regions to emerge. And what we’re saying is actually, no, you only really need a couple of months.”

Because their data on the area of the brain that responds to scenes was not as strong as for the other locations they looked at, the researchers now plan to pursue additional studies of that region, this time showing babies images on a much larger screen that will more closely mimic the experience of being within a scene. For that study, they plan to use near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), a non-invasive imaging technique that doesn’t require the participant to be inside a scanner.

“That will let us ask whether young babies have robust responses to visual scenes that we underestimated in this study because of the visual constraints of the experimental setup in the scanner,” Saxe says.

The researchers are now further analyzing the data they gathered for this study in hopes of learning more about how development of the fusiform face area progresses from the youngest babies they studied to the oldest. They also hope to perform new experiments examining other aspects of cognition, including how babies’ brains respond to language and music.

###

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the McGovern Institute, and the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines.

Journal

Current Biology

DOI

10.1016/j.cub.2021.10.064

Subject of Research

People

Article Title

Selective responses to faces, scenes, and bodies in the ventral visual pathway of infants

Article Publication Date

15-Nov-2021