Credit: von Brünneck / Charité

– Joint press release by the MDC and Charité –

A new cancer-fighting gene therapy has been applied in the clinic for the first time after 20 years of preliminary research in the laboratories of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Other initiatives to have emerged from this work include biotech start-up T-knife. A few weeks ago, the first multiple myeloma patient received an infusion of her body’s own immune cells (the so-called T cells) that had been genetically modified to enable their receptors to recognize and fight the cancer. Multiple myeloma is one of the most common cancers affecting the bone and bone marrow.

Twelve patients are to undergo this treatment over the course of the two-year phase I trial. “The primary concern right now is to make sure this new form of immunotherapy and gene therapy is safe for patients,” says Professor Antonio Pezzutto, who is leading the study at the Medical Department, Division of Hematology, Oncology and Tumor Immunology on Charité’s Campus Benjamin Franklin. “We believe we will see indications that the principle behind the therapy is effective and hope that the patients will benefit,” adds Pezzutto, “but it is in the next clinical phase that the effectiveness of the therapy will be investigated in a large number of people.” The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) is funding the cooperative project with €4 million.

T-cell training

T cells monitor our body and protect it from diseases such as viral infections. Infected cells can be recognized by the viral antigens that appear as typical markers on their surface. If a T cell detects an antigen with the help of its receptor, it either destroys the affected cell or triggers a wider immune response. Cancer cells also have special antigens on their surface, but the problem is that the immune system often does not recognize them as malignant and therefore does not fight them.

This could all be about to change with the new T-cell gene therapy, which was developed by a team led by Professor Thomas Blankenstein, head of the Molecular Immunology and Gene Therapy Lab at the MDC and former director of the Institute of Medical Immunology at Charité. The researchers want to teach the study participants’ T cells to identify cancer cells as invaders. “Our preclinical experiments suggest that this should be possible without damaging any healthy tissue in the patients,” says Blankenstein.

A unique technology platform

The research team started out focusing on the antigen MAGE-A1 as a potential candidate for treating multiple myeloma. This protein is a typical distinguishing feature that appears on the surface of cancer cells and is more common in multiple myeloma. The scientists were able to produce a specific T-cell receptor that recognizes this particular antigen, and thus the cell that carries it, as malignant and dangerous.

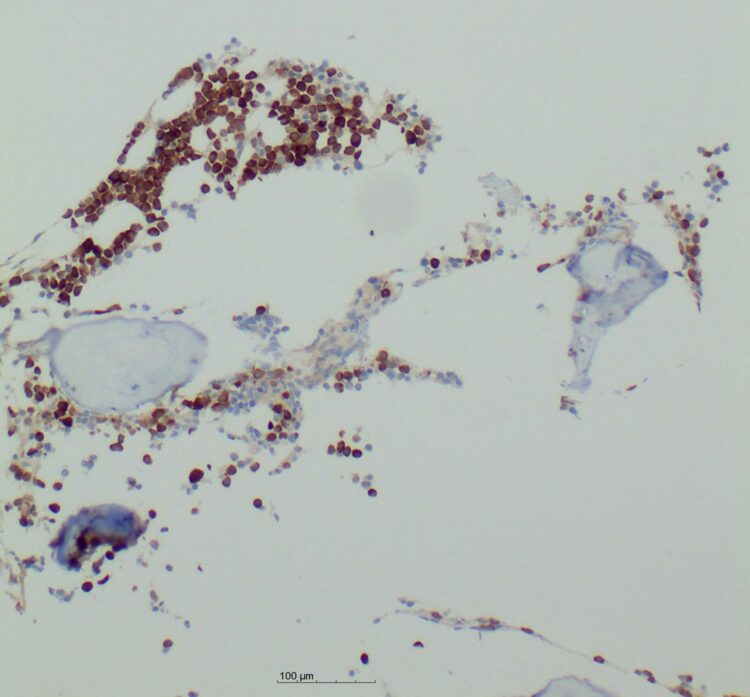

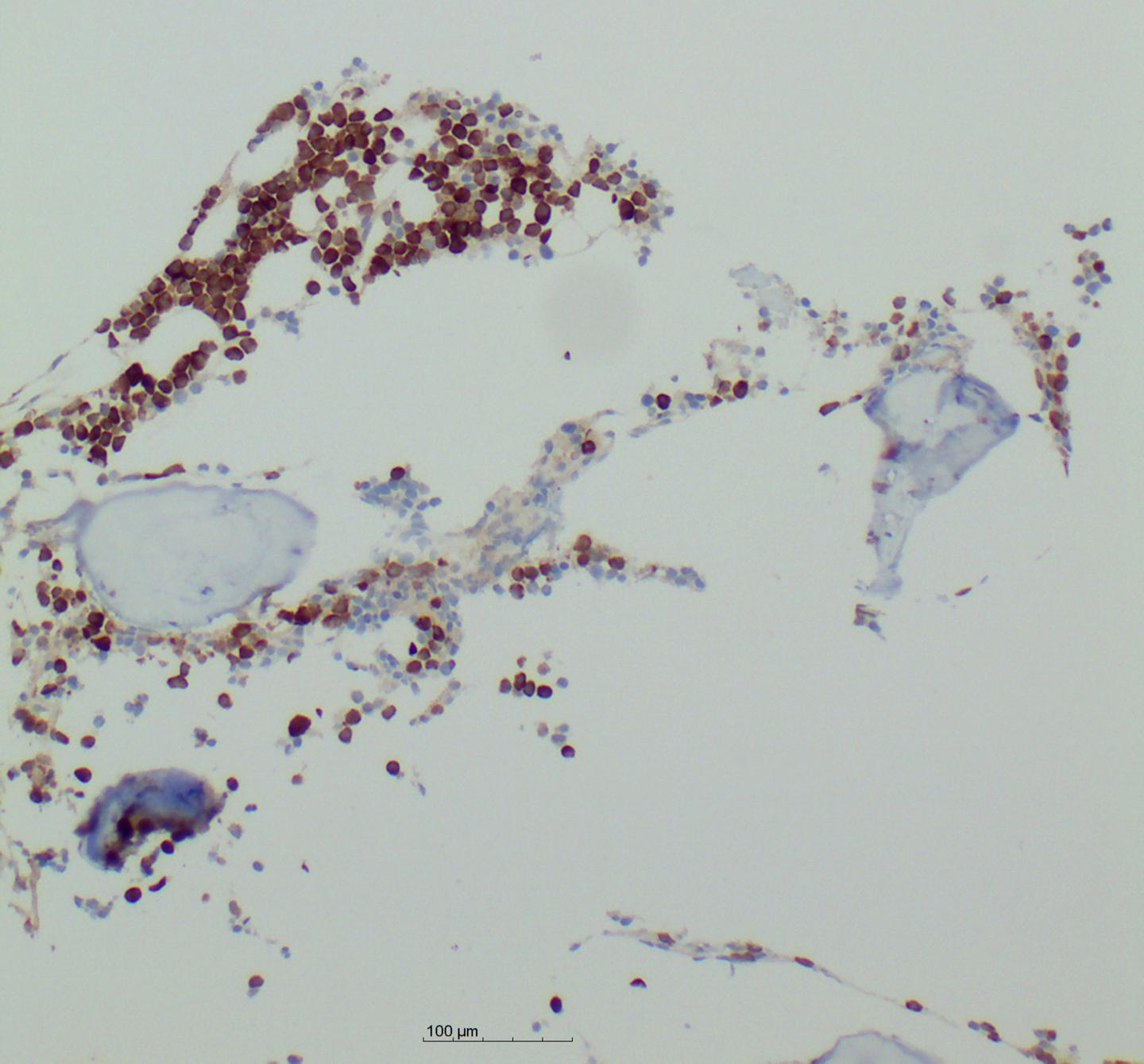

This was possible thanks to a unique technology platform that Blankenstein’s team developed for the gene therapy – a transgenic mouse with an exclusively human T-cell repertoire. “If the transgenic mouse is immunized with a human antigen, it starts to produce only T cells with matching receptors, which can then be easily isolated,” explains Blankenstein. “This enables us to obtain the genetic blueprint of receptors of human origin, which cannot usually be obtained from humans. The T-cell receptors are then subjected to a series of safety and efficacy tests, which is very important to ensure the safety of this treatment for patients with bone marrow cancer.”

How the treatment works

The cell products for the entire study are being manufactured at the GMP Facility for Cellular Therapies at the Clinical Research Center (ECRC), a joint institution of the MDC and Charité that specializes in the production of cell and gene therapies in clean rooms. First, doctors took T cells from the initial patient and handed them over to specialists at the ECRC. Here, the genetic information of the specific receptor was inserted into the patient’s own T cells, which were then activated and multiplied. A few days before the treatment, the patient received chemotherapy to eliminate other immune cells in the body. This makes the attack on the cancer cells particularly effective. After being treated with her own genetically modified T cells, the patient was monitored for a fortnight as an inpatient at Charité. She has undergone regular examinations since then, and these will continue into the future. The treating physicians include Matthias Obenaus, who isolated and characterized this T-cell receptor as part of his doctoral thesis.

In addition to MAGE-A1, the team has discovered other promising antigens that occur in other cancers. T-knife is currently in the process of manufacturing and testing suitable receptors. If successful, this should enable more and more patients to benefit from the MDC and Charité’s new gene therapy in the future. “We are excited to learn the results of the study and hope that this gene therapy will provide us with a new and promising way to better fight cancer in the future,” says Blankenstein.

###

Scientific contacts

Professor Thomas Blankenstein

Head of the Molecular Immunology and Gene Therapy Lab

Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC)

Tel.: +49 30 9406-2816

[email protected]

Matthias Obenaus

Medical Department, Division of Hematology, Oncology and Tumor Immunology

Campus Benjamin Franklin

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Tel.: +49 30 450 513 382

[email protected]

Clinical trials

Before new drugs are approved for regular use they are tested for safety and efficacy in a standardized procedure. In a phase I clinical trial, a therapeutic agent is used in humans for the first time – after extensive preliminary testing – in order to obtain preliminary data on tolerability and safety as well as further effects on the organism. The number of participants is small. If no serious side effects occur and there are initial indications of possible efficacy, a phase II clinical trial follows. Here, tolerability and side effects are determined in a somewhat larger number of patients and the dosage is optimized with regard to possible efficacy. Only in phase III trials, which often last for years and include a large number of participants, can proof of the efficacy of the new substance be provided. For this purpose, the new substance is compared with other available and already approved drugs. Only phase III clinical trials provide the data needed for regulatory approval.

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) was founded in Berlin in 1992. It is named for the German-American physicist Max Delbrück, who was awarded the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. The MDC’s mission is to study molecular mechanisms in order to understand the origins of disease and thus be able to diagnose, prevent and fight it better and more effectively. In these efforts the MDC cooperates with the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) as well as with national partners such as the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and numerous international research institutions. More than 1,600 staff and guests from nearly 60 countries work at the MDC, just under 1,300 of them in scientific research. The MDC is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (90 percent) and the State of Berlin (10 percent), and is a member of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers.

Media Contact

Jana Ehrhardt-Joswig

[email protected]

Original Source

https:/