Credit: Illustration: Julia Jullesova

Rituximab, an anti-cancer drug targeting the membrane protein CD20, was the first approved therapeutic antibody against B tumor cells. Immunologists at the University of Freiburg have now solved a mystery about how it works. A team headed by Professor Dr. Michael Reth used cell cultures, healthy cells, and cells from cancer patients to investigate how CD20 organizes the nanostructures on the B cell membrane. If the protein is missing or Rituximab binds to it, the organization of the B cell surface changes. The resting B cell is activated in the process. The team has published the research in the journal PNAS as part of contributions by new members of the National Academy of Science.

B cells are white blood cells and part of the immune system. When they recognize foreign substances, they develop into plasma cells. These produce antibodies that fight off bacteria, viruses or tumor cells. Reth’s team used CRISPR/Cas9 gene scissors to remove the gene of CD20 in tumor cell lines and in healthy B cells. The researchers then analyzed on a nanoscale how the proteins on the surface of the B cells form new interactions with other receptors. “These results are based on our research on nanoclusters of membrane proteins and their regulation of immune cells,” says Reth.

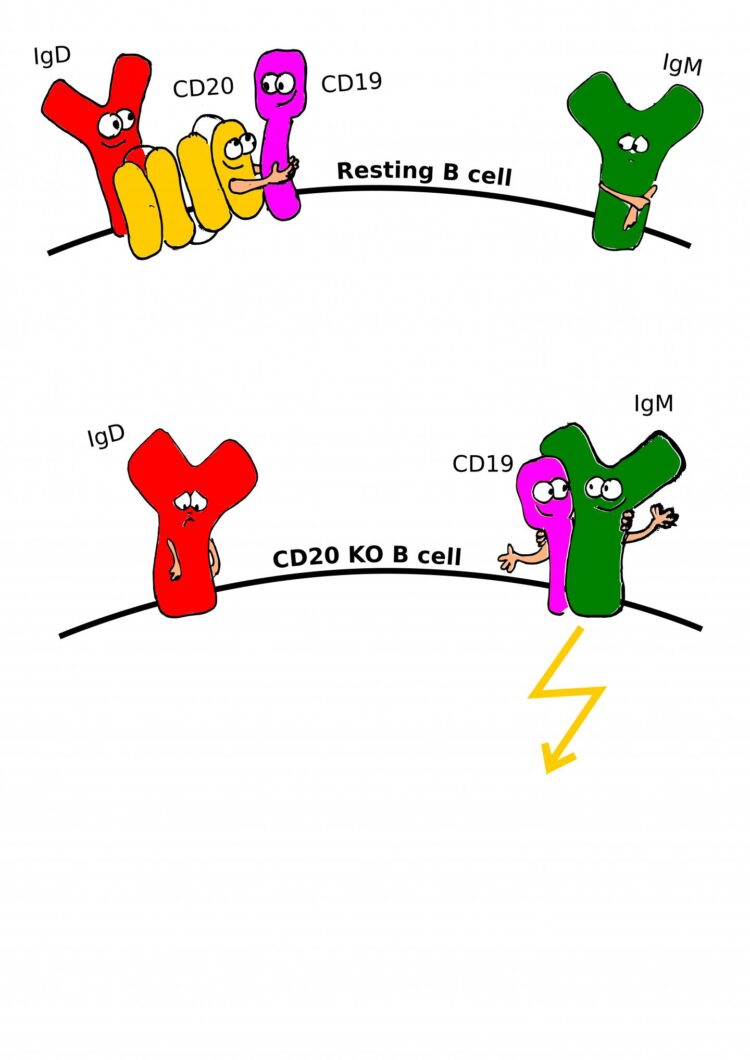

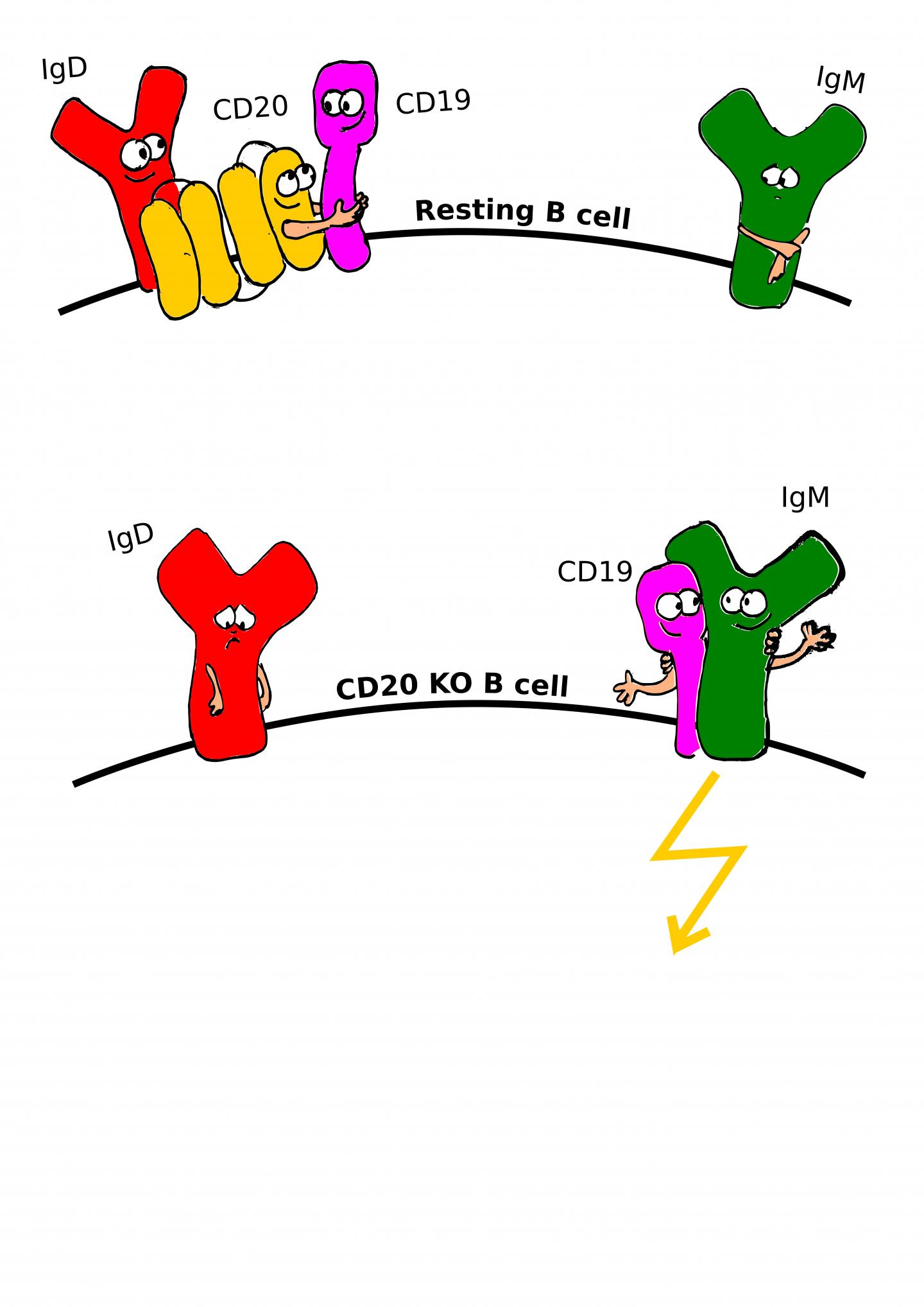

“The protein CD20 keeps apart the B cell antigen receptor of the IgM class and the coreceptor CD19. CD20 thereby ensures the resting state of the B cells,” Reth explains. Only when these proteins interact within the membrane and form an IgM/CD19 complex – normally as a reaction to an exogenous antigen – is the immune cell’s defense fully activated. Reth’s team found that this complex also forms in cells without CD20 or after treatment with Rituximab.

The binding of Rituximab, which is prescribed against B-cell lymphomas as well as B-cell autoimmune diseases, signals to other immune cells to destroy all CD20-bearing B cells. This led the researchers to examine blood from patients during treatment with Rituximab. “We found that CD20 bound by Rituximab on the B cell surface disappears very quickly. These B cells then remain undetected, but are activated by the absence of CD20,” explains Kathrin Kläsener, first author of the study.

The B cells thus altered eventually proliferate and can develop into plasma cells. These plasma cells no longer possess CD20 and are therefore no longer accessible to Rituximab. “In the blood tests of relapse patients who have been treated with Rituximab, we also found increased amounts of plasma cells,” Kläsener says. “Until now, it was unclear what important function the protein CD20 had and why some patients relapsed after treatment with Rituximab. Now we understand why,” Reth explains. “This could help develop even more effective therapies in the future.”

###

Michael Reth is Professor of Molecular Immunology and co-speaker of BIOSS – Centre for Biological Signalling Studies He is also a member of the cluster of excellence CIBSS – Centre for Integrative Biological Signalling Studies

Publication:

Kläsener, K., Jellusova, J., Andrieux, G, Salzer, U., Böhler, C., Steiner, S. N., Albinus, J. B., Cavallari, M., Süß, B., Voll, R. E., Boerries, M., Wollscheid, B. and Reth, M. (2021): CD20 as a gatekeeper of the resting state of human B cells. In: PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2021342118

Contact:

Professor Dr. Michael Reth

Molecular Immunology working group

Institute of Biology III

University of Freiburg

Phone: 0761/203- 2718

[email protected]

Media Contact

Professor Dr. Michael Reth

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.