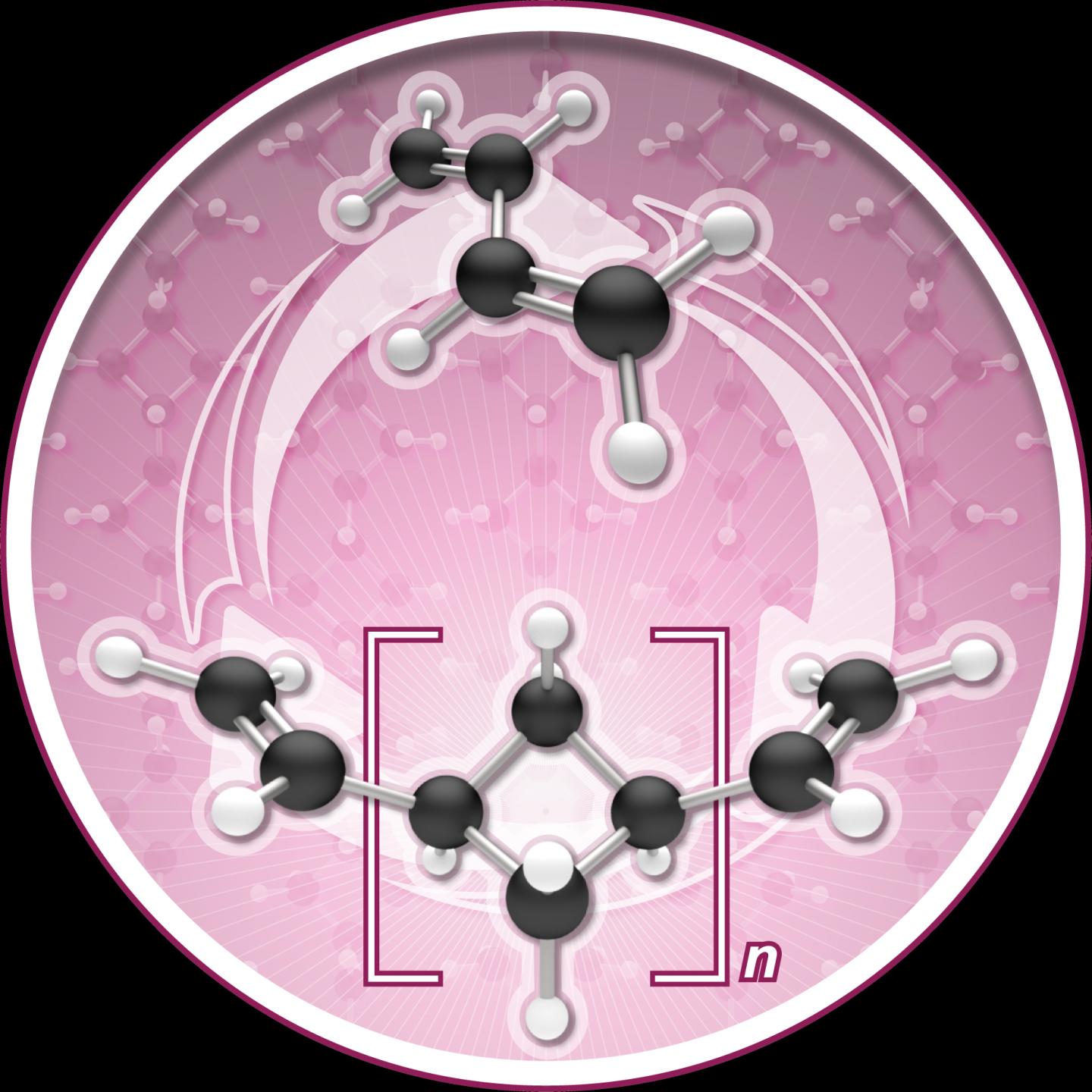

New polybutadiene molecule enchains in squares, a microstructure that enables it to depolymerize under certain conditions, advancing options for closed-loop recycling.

Credit: Figure by Jonathan Darmon of the Princeton University Department of Chemistry.

As the planet’s burden of rubber and plastic trash rises unabated, scientists increasingly look to the promise of closed-loop recycling to reduce waste. A team of researchers at Princeton’s Department of Chemistry announces the discovery of a new polybutadiene molecule – from a material known for over a century and used to make common products like tires and shoes – that could one day advance this goal through depolymerization.

The Chirik lab reports in Nature Chemistry that during polymerization the molecule, named (1,n’-divinyl)oligocyclobutane, enchains in a repeating sequence of squares, a previously unrealized microstructure that enables the process to go backwards, or depolymerize, under certain conditions.

In other words, the butadiene can be “zipped up” to make a new polymer; that polymer can then be unzipped back to a pristine monomer to be re-used.

The research is still at an early stage and the material’s performance attributes have yet to be thoroughly explored. But the Chirik lab has provided a conceptual precedent for a chemical transformation not generally thought practical for certain commodity materials.

In the past, depolymerization has been accomplished with expensive niche or specialized polymers and only after a multitude of steps, but never from a raw material as common as that used to make polybutadiene, one of the top seven primary petrochemicals in the world. Butadiene is an abundant organic compound and a major byproduct of fossil fuel development. It is used to make synthetic rubber and plastic products.

“To take a really common chemical that people have been studying and polymerizing for many decades and make a fundamentally new material out of it – let alone have that material have interesting innate properties – not only is that unexpected, it’s really a big step forward. You wouldn’t necessarily expect there still to be fruit on that tree,” said Alex E. Carpenter, a staff chemist with ExxonMobil Chemical, a collaborator on the research.

“The focus of this collaboration for us has been on developing new materials that benefit society by focusing on some new molecules that [Princeton chemist] Paul Chirk has discovered that are pretty transformative,” Carpenter added.

“Humankind is good at making butadiene. It’s very nice when you can find other useful applications for this molecule, because we have plenty of it.”

Catalysis with Iron

The Chirik lab explores sustainable chemistry by investigating the use of iron – another abundant natural material – as a catalyst to synthesize new molecules. In this particular research, the iron catalyst clicks the butadiene monomers together to make oligocyclobutane. But it does so in a highly unusual square structural motif. Normally, enchainment occurs with an S-shaped structure that is often described as looking like spaghetti.

Then, to affect depolymerization, oligocyclobutane is exposed to a vacuum in the presence of the iron catalyst, which reverses the process and recovers the monomer. The Chirik lab’s paper, “Iron Catalyzed Synthesis and Chemical Recycling of Telechelic, 1,3-Enchained Oligocyclobutanes,” identifies this as a rare example of closed-loop chemical recycling.

The material also has intriguing properties as characterized by Megan Mohadjer Beromi, a postdoctoral fellow in the Chirik lab, together with chemists at ExxonMobil’s polymer research center. For instance, it is telechelic, meaning the chain is functionalized on both ends. This property could enable it to be used as a building block in its own right, serving as a bridge between other molecules in a polymeric chain. In addition, it is thermally stable, meaning it can be heated to above 250-degrees C without rapid decomposition.

Finally, it exhibits high crystallinity, even at a low molecular weight of 1,000 grams per mol (g/mol). This could indicate that desirable physical properties – like crystallinity and material strength – can be achieved at lower weights than generally assumed. The polyethylene used in the average plastic shopping bag, for example, has a molecular weight of 500,000g/mol.

“One of the things we demonstrate in the paper is that you can make really tough materials out of this monomer,” said Chirik, Princeton’s Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Chemistry. “The energy between polymer and monomer can be close, and you can go back and forth, but that doesn’t mean the polymer has to be weak. The polymer itself is strong.

“What people tend to assume is that when you have a chemically recyclable polymer, it has to be somehow inherently weak or not durable. We’ve made something that’s really, really tough but is also chemically recyclable. We can get pure monomer back out of it. And that surprised me. That’s not optimized. But it’s there. The chemistry’s clean.

“I honestly think this work is one of the most important things to ever come out of my lab,” said Chirik.

Ditching the ethylene

The project stretches back a few years to 2017, when C. Rose Kennedy, then a postdoc in the Chirik lab, noticed a viscous liquid accumulating at the bottom of a flask during a reaction. Kennedy said she was expecting something volatile to form, so the result spurred her curiosity. Digging into the reaction, she discovered a distribution of oligomers – or nonvolatile products with a low molecular weight – that indicated polymerization had taken place.

“Knowing what we knew about the mechanism already, it was pretty clear right away how this would be possible to click them together in a different or continuous way. We immediately recognized this could be something potentially extremely valuable,” said Kennedy, now an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Rochester.

At that early point, Kennedy was enchaining butadiene and ethylene. It was Mohadjer Beromi who later surmised that it would be possible to remove the ethylene altogether and just use neat butadiene at elevated temperatures. Mohadjer Beromi “gave” the four-carbon butadiene to the iron catalyst, and that yielded the new polymer of squares.

“We knew that the motif had the propensity to be chemically recycled,” said Mohadjer Beromi. “But I think one of the new and really interesting features of the iron catalyst is that it can do [2+2] cycloadditions between two dienes, and that’s what this reaction essentially is: it’s a cycloaddition where you’re linking two olefins together to make a square molecule over and over again.

“It’s the coolest thing I’ve ever worked on in my life.”

To further characterize oligocyclobutane and understand its performance properties, the molecule needed to be scaled and studied at a larger facility with expertise in new materials.

“How do you know what you made?” Chirik asked. “We used some of the normal tools we have here at Frick. But what really matters is the physical properties of this material, and ultimately what the chain looks like.”

For that, Chirik traveled to Baytown, Texas last year to present the lab’s findings to ExxonMobil, which decided to support the work. An integrated team of scientists from Baytown were involved in computational modeling, X-ray scattering work to validate the structure, and additional characterization studies.

Recycling 101

The chemical industry uses a small number of building blocks to make most commodity plastic and rubber. Three such examples are ethylene, propylene, and butadiene. A major challenge of recycling these materials is that they often need to be combined and then bolstered with other additives to make plastics and rubbers: additives provide the performance properties we want – the hardness of a toothpaste cap, for example, or the lightness of a grocery bag. These “ingredients” all have to be separated again in the recycling process.

But the chemical steps involved in that separation and the input of energy required to bring this about make recycling prohibitively expensive, particularly for single-use plastics. Plastic is cheap, lightweight, and convenient, but it was not designed with disposal in mind. That, said Chirik, is the main, snowballing problem with it.

As a possible alternative, the Chirik research demonstrates that the butadiene polymer is almost energetically equal to the monomer, which makes it a candidate for closed-loop chemical recycling.

Chemists liken the process of producing a product from a raw material to rolling a boulder up a hill, with the peak of the hill as the transition state. From that state, you roll the boulder down the other side and end up with a product. But with most plastics, the energy and cost to roll that boulder backwards up the hill to recover its raw monomer are staggering, and thus unrealistic. So, most plastic bags and rubber products and car bumpers end up in landfills.

“The interesting thing about this reaction of hooking one unit of butadiene onto the next is that the ‘destination’ is only very slightly lower in energy than the starting material,” said Kennedy. “That’s what makes it possible to go back in the other direction.”

In the next stage of research, Chirik said his lab will focus on the enchainment, which at this point chemists have only achieved on average up to 17 units. At that chain length, the material becomes crystalline and so insoluble that it falls out of the reaction mixture.

“We have to learn what to do with that,” said Chirik. “We’re limited by its own strength. I would like to see a higher molecular weight.”

Still, researchers are excited about the prospects for oligocyclobutane, and many investigations are planned in this continuing collaboration towards chemically recyclable materials.

“The current set of materials that we have nowadays doesn’t allow us to have adequate solutions to all the problems we’re trying to solve,” said Carpenter. “The belief is that, if you do good science and you publish in peer-reviewed journals and you work with world-class scientists like Paul, then that’s going to enable our company to solve important problems in a constructive way.

“This is about understanding really cool chemistry,” he added, “and trying to do something good with it.”

###

In addition to Chirik and Mohadjer Beromi, additional authors on this paper include C. Rose Kennedy, formerly of the Chirik Lab; Jarod M. Younker, ExxonMobil Chemical; Alex E. Carpenter, formerly of ExxonMobil Chemical; Sarah J. Mattler, ExxonMobil Chemical; and Joseph A. Throckmorton, ExxonMobil Chemical. Correspondence should be addressed to [email protected].

Initial funding for this work was provided by Firmenich, and the National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F32 GM134610 & F32 GM126640). Funding was also provided by ExxonMobil through Princeton E-filliates Partnership.

Media Contact

Wendy Plump

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.