Credit: Dr Patrick Ehi Imoisili, Therese van Wyk, University of Johannesburg.

A luxury automobile is not really a place to look for something like sisal, hemp or wood. Yet auto makers have been using natural fibres for decades.

Some high-end sedans and coupes use these in composite materials for interior door panels; engine, interior and noise insulation; and internal engine covers among other uses.

Unlike steels or aluminium, natural fibre composites do not rust or corrode. They can also be durable and easily molded.

The biggest benefits fibre reinforced polymer composites bring to cars are the light weight, good crash properties, and noise and vibration reducing characteristics.

But making more parts of a vehicle from renewable sources is a challenge. Natural fibre polymer composites can crack, break and bend. The reasons for this include too low tensile, flexural and impact strength in the composite material.

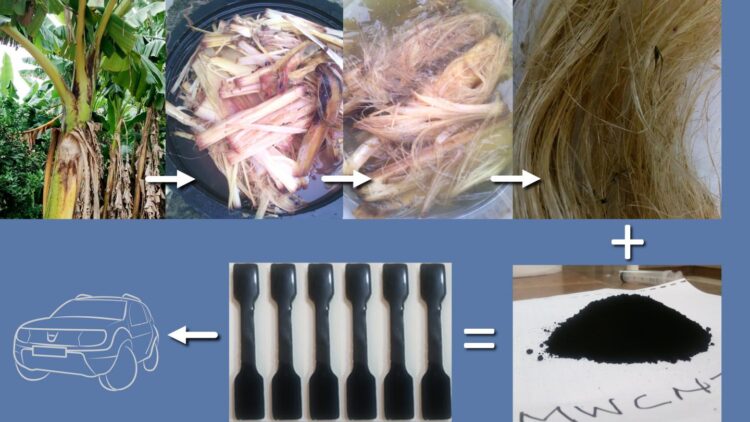

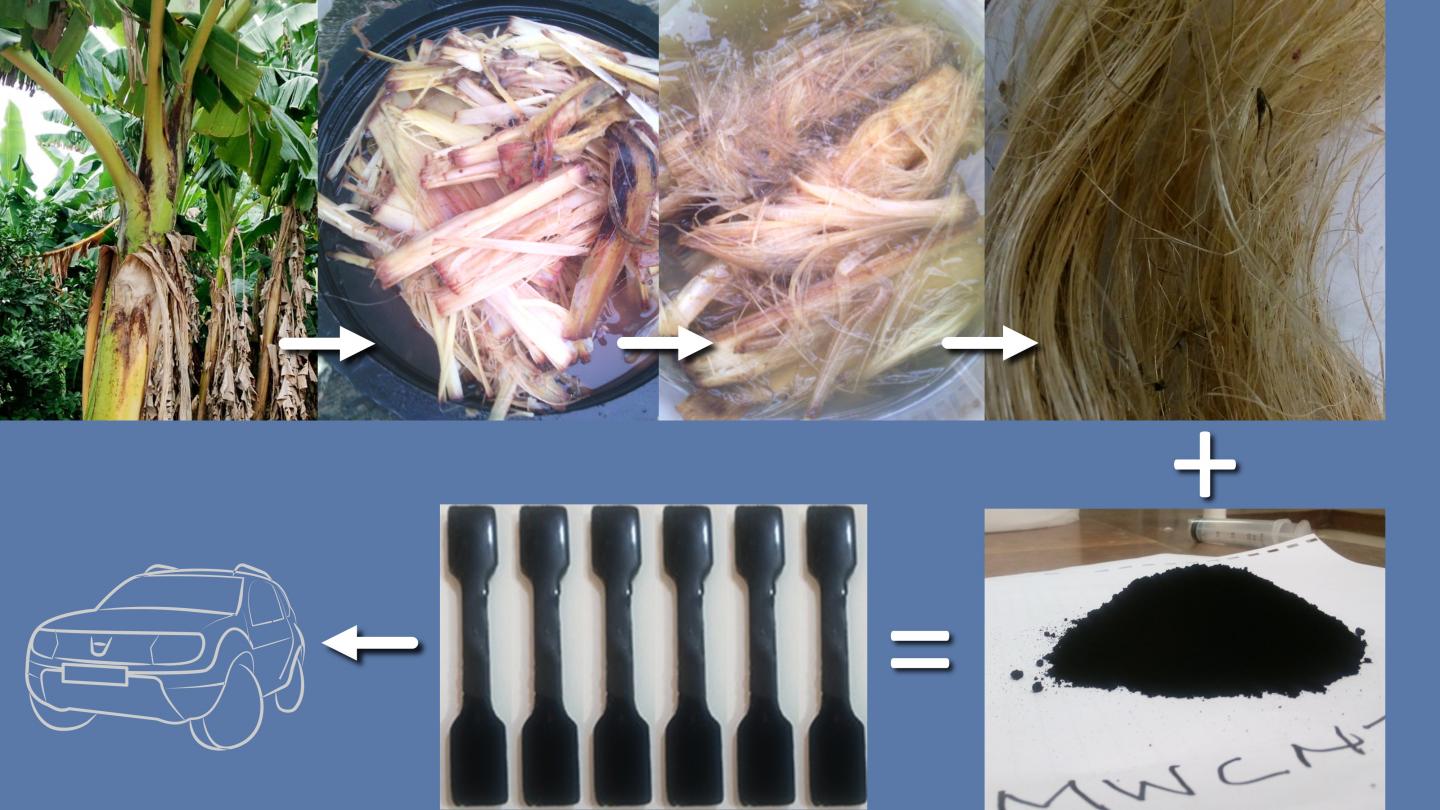

Researchers from the University of Johannesburg have now demonstrated that plantain, a starchy type of banana, is a promising source for an emerging type of composite materials for the automotive industry. The natural plantain fibres are combined with carbon nanotubes and epoxy resin to form a natural fibre-reinforced polymer hybrid nanocomposite material.

Plantain is a year-round staple food crop in tropical regions of Africa, Asia and South America. Many types of plantain are eaten cooked.

The researchers moulded a composite material from epoxy resin, treated plantain fibers and carbon nanotubes. The optimum amount of nanotubes was 1% by weight of the plantain-epoxy resin combined.

The resulting plantain nanocomposite was much stronger and stiffer than epoxy resin on its own.

The composite had 31% more tensile and 34% more flexural strength than the epoxy resin alone. The nanocomposite also had 52% higher tensile modulus and 29% higher flexural modulus than the epoxy resin alone.

“The hybridization of plantain with multi-walled carbon nanotubes increases the mechanical and thermal strength of the composite. These increases make the hybrid composite a competitive and alternative material for certain car parts,” says Prof Tien-Chien Jen.

Prof Jen is the lead researcher in the study and the Head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering Science at the University of Johannesburg.

Natural fibres vs metals

Producing car parts from renewable sources have several benefits, says Dr Patrick Ehi Imoisili. Dr Imoisili is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering Science at the University of Johannesburg.

“There is a trend of using natural fibre in vehicles. The reason is that natural fibres composites are renewable, low cost and low density. They have high specific strength and stiffness. The manufacturing processes are relatively safe,” says Imoisili.

“Using car parts made from these composites, can reduce the mass of a vehicle. That can result in better fuel-efficiency and safety. These components will not rust or corrode like metals. Also, they can be stiff, durable and easily molded,” he adds.

However, some natural fibre reinforced polymer composites currently have disadvantages such as water absorption, low impact strength and low heat resistance. Car owners can notice effects such as cracking, bending or warping of a car part, says Imoisili.

Standardised tests

The researchers subjected the plantain nanocomposite to a series of standardised industrial tests. These included ASTM Test Methods D638 and D790; impact testing according to the ASTM A-370 standard; and ASTM D-2240.

The tests showed that a composite with 1% nanotubes had the best strength and stiffness, compared to epoxy resin alone.

The plantain nanocomposite also showed marked improvement in micro hardness, impact strength and thermal conductivity compared to epoxy resin alone.

Moulding a nanocomposite from natural fibres

The researchers compression-moulded a ‘stress test object’. They used 1 part inedible plantain fibres, 4 parts epoxy resin and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. The epoxy resin and nanotubes came from commercial suppliers. The epoxy was similar to resins that auto manufacturers use in certain car parts.

The plantain fibres came from the ‘trunks’ or pseudo-stems, of plantain plants in the south-western region of Nigeria. The pseudo-stems consist of tightly-overlapping leaves.

The researchers treated the plantain fibers with several processes. The first process is an ancient method to separate plant fibres from stems, called water-retting.

In the second process, the fibres were soaked in a 3% caustic soda solution for 4 hours. After drying, the fibres were treated with high-frequency microwave radiation of 2.45GHz at 550W for 2 minutes.

The caustic soda and microwave treatments improved the bonding between the plantain fibers and the epoxy resin in the nanocomposite.

Next, the researchers dispersed the nanotubes in ethanol to prevent ‘bunching’ of the tubes in the composite. After that, the plantain fibres, nanotubes and epoxy resin were combined inside a mold. The mold was then compressed with a load for 24 hours at room temperature.

Food crop vs industrial raw material

Plantain is grown in tropical regions worldwide. This includes Mexico, Florida and Texas in North America; Brazil, Honduras, Guatemala in South and Central America; India, China, and Southeast Asia.

In West and Central Africa, farmers grow plantain in Cameroon, Ghana, Uganda, Rwanda, Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire and Benin.

Using biomass from major staple food crops can create problems in food security for people with low incomes. In addition, the automobile industry will need access to reliable sources of natural fibres to increase use of natural fibre composites.

In the case of plantains, potential tensions between food security and industrial uses for composite materials are low. This is because plantain farmers discard the pseudo-stems as agro-waste after harvest.

###

INTERVIEWS: For email interviews or questions, contact Dr Patrick Ehi Imoisili at [email protected].

The research was supported by funding from the University Research Committee of the University of Johannesburg and the National Research Foundation of South Africa.

Media Contact

Ms Therese van Wyk (UTC + 2, Johannesburg)

[email protected]

Related Journal Article

http://dx.